Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

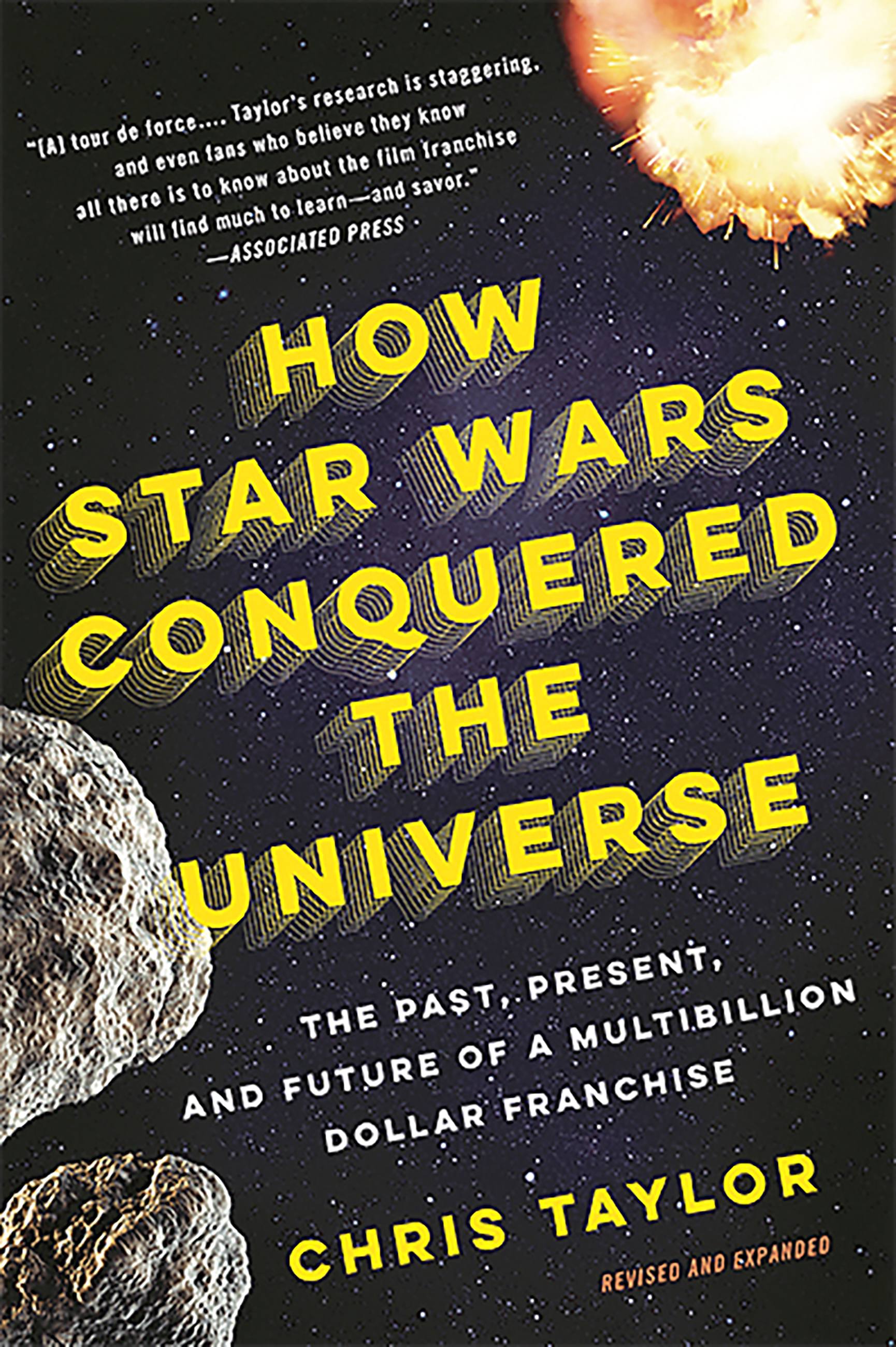

How Star Wars Conquered the Universe

The Past, Present, and Future of a Multibillion Dollar Franchise

Contributors

By Chris Taylor

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 6, 2015

- Page Count

- 512 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465049899

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 6, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In How Star Wars Conquered the Universe, veteran journalist Chris Taylor traces the series from the difficult birth of the original film through its sequels, the franchise’s death and rebirth, the prequels, and the preparations for a new trilogy. Providing portraits of the friends, writers, artists, producers, and marketers who labored behind the scenes to turn Lucas’s idea into a legend, Taylor also jousts with modern-day Jedi, tinkers with droid builders, and gets inside Boba Fett’s helmet, all to find out how Star Wars has attracted and inspired so many fans for so long.

Since the first film’s release in 1977, Taylor shows, Star Wars has conquered our culture with a sense of lightness and exuberance, while remaining serious enough to influence politics in far-flung countries and spread a spirituality that appeals to religious groups and atheists alike. Controversial digital upgrades and poorly received prequels have actually made the franchise stronger than ever. Now, with a savvy new set of bosses holding the reins and Episode VII on the horizon, it looks like Star Wars is just getting started.

An energetic, fast-moving account of this creative and commercial phenomenon, How Star Wars Conquered the Universe explains how a young filmmaker’s fragile dream beat out a surprising number of rivals to gain a diehard, multigenerational fan base — and why it will be galvanizing our imaginations and minting money for generations to come.

-

"Exhaustive.... those of us more casually in tune with the Force will find more than a few tasty nuggets."Wall Street Journal

-

"Insanely microresearched and breezily written."New York Times Book Review

-

"An excellent look at the genesis of Star Wars.... [Taylor's] put together a volume that's honest and interesting--and one that's completely reignited my passion for Star Wars."io9

-

"An unconventional approach that serves to bring a spark of life that might otherwise go missing from a straightforward commercial or cinematic look at Star Wars."Washington Post

-

"Even obsessives will likely find much that's news to them ... worthy of being savored ... amusing ... reveals what a huge role serendipity played in Star Wars."New York Post

-

"Delivers a payload of information... you will find intense emotions in its observations of a battle for autonomy within corporate cinema, and to the public that swoons for Lucas' products."San Francisco Chronicle

-

"An immensely readable look at the worldwide impact of the Star Wars saga over the decades."McClatchy

-

"Taylor brings a genuine love of pop and nerd culture to this comprehensive retrospective on one of the 20th century's most popular film series.... Taylor has compiled an impressive collection of background research and insider info that any fan would be glad to own."Publishers Weekly

-

"Taylor's fan-boy enthusiasm coupled with his inviting narrative style make this a fun and informative read for sf enthusiasts, media studies and marketing students, film industry professionals, and aspiring Jedi Knights."Library Journal

-

"It's impossible to imagine a Star Wars fan who wouldn't love this book.... It really is hard to imagine a book about Star Wars being any more comprehensive than this one. It's full of information and insight and analysis, and it's so engagingly written that it's a pure joy to read.... There are plenty of books about Star Wars, but very few of them are essential reading. This one goes directly to the top of the pile."Booklist (starred review)

-

"A smart, engaging book...welcome reading for fans of Star Wars--or, for that matter, of THX 1138."Kirkus Reviews

-

"This is a wildly entertaining book, and if it's not the definitive history of the making of Star Wars, I don't know what is. But it's more than that: it tells a rollicking good story about storytelling itself, about the intersection between art and commerce, and paints surely the most complete and deeply felt portrait of George Lucas to date."Dave Eggers, author of The Circle and A Hologram for the King

-

"Smart. Eloquent. Definitive. This is the book you're looking for."Lev Grossman, author of the New York Times bestselling Magicians trilogy

-

"It's impossible to overstate the cultural, social and even political impact of Star Wars. It started as a balm for a people racked by moral confusion, a juvenile bolt hole for a nation with shattered self-esteem, but the blast wave of enthusiasm and love it inspired was to engulf the planet. Culturally speaking it is, quite simply, the Force. Chris Taylor's affectionate and hugely entertaining book tracks the phenomenon from inception to dominance and with a wry smile, asks us to 'look at the size of that thing!'"Simon Pegg, actor and Star Wars fan

-

"Every Star Wars fan should pick up a copy of How Star Wars Conquered the Universe.... Taylor's extensive exploration of the history of Star Wars and the impact it has had on popular culture makes for an eye-opening and entertaining read.... This book remains a necessary item for any bookshelf."The Wookiee Gunner

-

"Whether they read the novelization of the first Star Wars before the film came out, like me, or were blown away by Revenge of the Sith, anyone touched by the most enduring space fantasy mythology of the past two generations will thrill to Taylor's passionate telling of the saga behind the saga: How a lonely tinkerer from a backwater town changed the world via interplanetary heroism. To Star Wars obsessives and those wanting to understand modern pop culture: this is absolutely the book you are looking for."Brian Doherty, author of This is Burning Man