By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

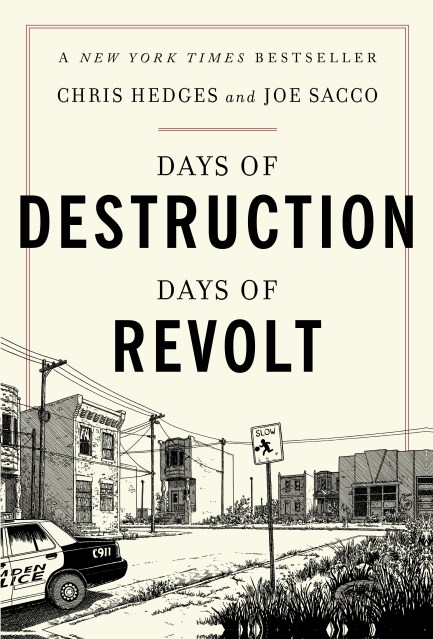

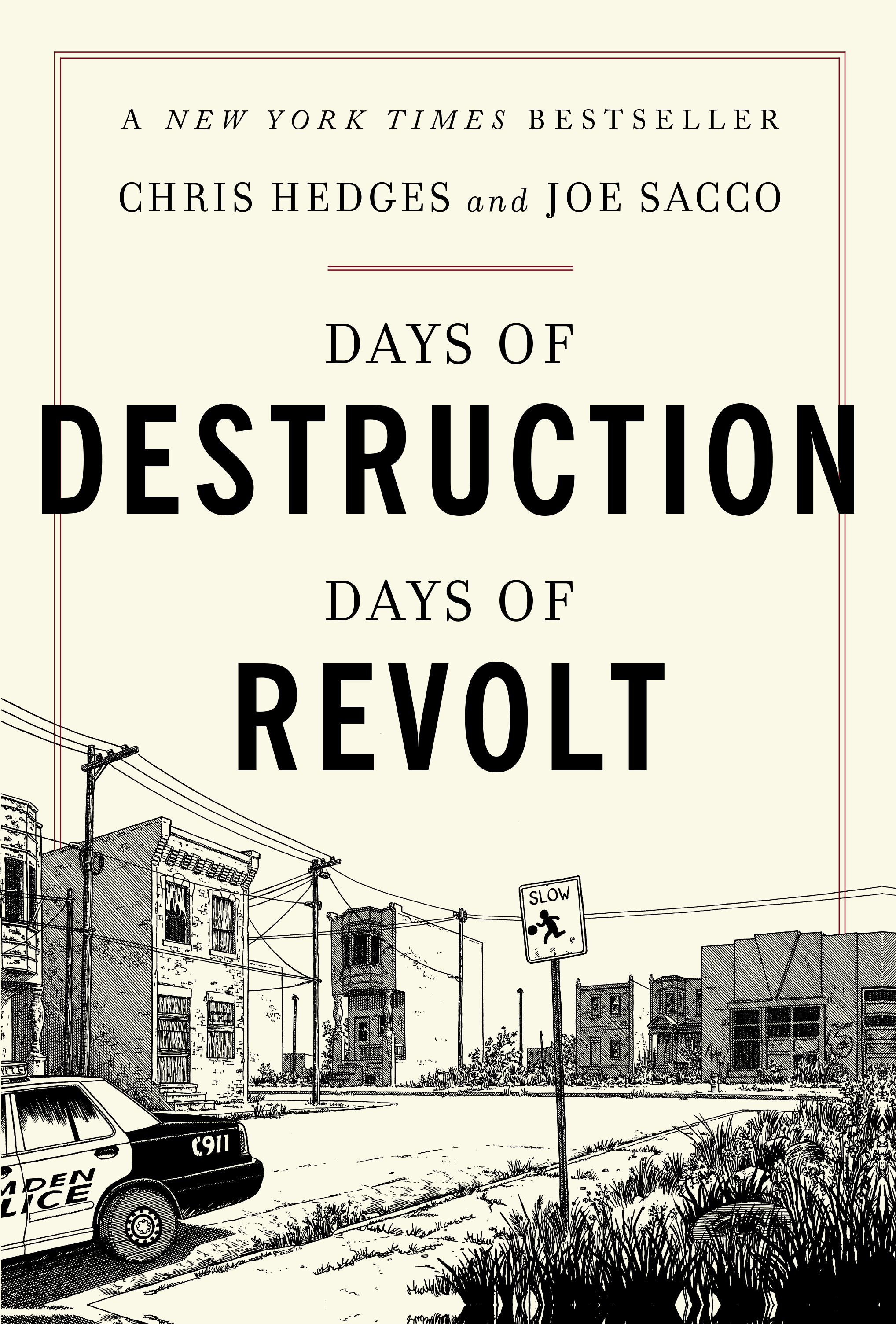

Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt

Contributors

By Chris Hedges

By Joe Sacco

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 8, 2014

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568584737

Price

$12.99Format

Format:

- ebook $12.99

- Trade Paperback $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 8, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Through a mixture of words and drawings, two award-winning journalists tell the stories of Americans surviving in the parts of the country most ravaged by capitalism, and the ways they manage to find hope

“As moving a portrait of poverty and as compelling a call to action as Michael Harrington’s The Other America.” —The Boston Globe

A New York Times Bestseller • A Washington Post Best Book of the Year

In this blend of rigorous journalism and graphic novel, Pulitzer Prize–winner Chris Hedges and award-winning cartoonist and journalist Joe Sacco set out to explore “sacrifice zones,” those areas in America that have been offered up for exploitation in the name of profit, progress, and technological advancement.

Beginning in the Great Plains, where Native American reservations bear the legacy of ethnic cleansing, Hedges and Sacco travel to some of the most neglected regions in the United States. They speak to families in Appalachia whose lives are subject to the whims of coal companies; they meet agricultural laborers who endure brutal working conditions and live below the poverty line. In each region, they seek pockets of optimism and resistance, from union organizers to neighbors who shelter each other, and ultimately end up in Zuccotti Park during the first days of the Occupy movement. Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt is the searing account of Sacco’s and Hedges’s travels.

-

A New York Times Bestseller

-

A Washington Post Best Book of the Year

-

“[Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt] is, without question, the most profoundly disquieting (and downright shocking) portrait of modern America in recent years, and one that is essential reading. . . . No one can remain unmoved or unsettled by its brilliantly documented reportage from the precipice of a society that prefers to turn a blind eye to its nightmarish underside.”The Times

-

“Sacco’s sections are uniformly brilliant. The tone is controlled, the writing smart, the narration neutral. . . . This is an important book. . . . [Hedges] is brilliant at depicting human life at the extremes of existence—from war to grinding poverty—and explaining the effects on the human psyche.”The New York Times

-

“The book is a primer for every American who is overwhelmed by the uncertainty of the stock market, who wonders where America's muscle went, and how much heavy lifting our kids will face.”Seattle Times

-

“A heartfelt, harrowing picture of post-capitalist America.”The Guardian

-

“Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt is as moving a portrait of poverty and as compelling a call to action as Michael Harrington’s The Other America, published in 1962.”The Boston Globe

-

“A growling indictment of corporate America.”Financial Times

-

“[A] brilliant combination of prose and graphic comics.”Ralph Nader

-

“Hedges writes with an undeniable sense of urgency. . . . A gripping and thoroughly researched polemic about the devastation wreaked by unfettered greed.”Grantland

-

“A unique hybrid of investigative journalism, graphic novel, and polemic.”Denver Post

-

“This is a book that should warm the hearts of political activists such as Naomi Klein or the nonagenerian Pete Seeger. . . . A polemic with a human face.”Globe and Mail

-

“Together, Sacco and Hedges might just have created a form that can speak across divides unbridgeable without the supplement of graphic narrative.”Public Books

-

“This searing indictment of our unsustainable society is unsettling. To keep our chance for dignity, we must do our part to champion the organizers and whistleblowers, committee members and protesters. Amen. Pass the word.”Brooklyn Rail

-

“Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt is a journey through contemporary American misery and what can be done to change the course, interpreted through the eyes of two of today’s most relevant literary journalists. . . . The graphics illustrate what words alone cannot, capturing a past as it’s told, where there’s no longer anything left to photograph.”Asbury Park Press

-

“The portraits . . . are powerful, and Sacco’s graphic artistry is compelling.”Philadelphia Inquirer

-

“Eloquently written and embellished by spare, desolate drawings from Joe Sacco, Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt is accessible and deeply uncomfortable.”Metro

-

“[A] harrowing study of modern poverty.”Chicago Tribune

-

“This book hit me in the gut. It will move you to engage in battle.”Ed Garvey, former executive director, National Football League Players Association

-

“This is an important book.”Winnipeg Free Press

-

“As quixotic as the quest may seem, Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt brings the rhetoric and the reality into a nobler focus after a very disturbing tour.”The Star-Ledger (New Jersey)

-

“The tales therein—both the intimate personal ones and the big sociopolitical ones—are as unsettling as they are impossible to put down.”Philadelphia Weekly

-

“A bleak, fist-shaking look at the effects of global capitalism in the United States.”Austin American-Statesman

-

“A riveting indictment of America’s failures.”Portland Monthly

-

“It’s rare that a book carries so much courage and conviction, forcing reflection and an urge to immediately rectify the problems.”Bookslut

-

“Brilliant.”The Capital Times

-

“A powerful social and political exploration.”Midwest Book Review

-

“An unabashedly polemic, angry manifesto that is certain to open eyes, intensify outrage and incite argument about corporate greed. . . . A call for a new American revolution, passionately proclaimed.”Kirkus, Starred Review

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use