Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

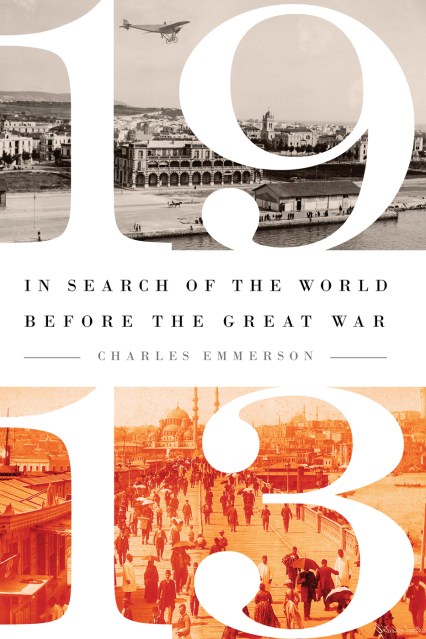

1913

In Search of the World Before the Great War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 7, 2013

- Page Count

- 544 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610392570

Price

$12.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 7, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In this illuminating history, Charles Emmerson liberates the world of 1913 from this “prelude to war” narrative, and explores it as it was, in all its richness and complexity. Traveling from Europe’s capitals, then at the height of their global reach, to the emerging metropolises of Canada and the United States, the imperial cities of Asia and Africa, and the boomtowns of Australia and South America, he provides a panoramic view of a world crackling with possibilities, its future still undecided, its outlook still open.

The world in 1913 was more modern than we remember, more similar to our own times than we expect, more globalized than ever before. The Gold Standard underpinned global flows of goods and money, while mass migration reshaped the world’s human geography. Steamships and sub-sea cables encircled the earth, along with new technologies and new ideas. Ford’s first assembly line cranked to life in 1913 in Detroit. The Woolworth Building went up in New York. While Mexico was in the midst of bloody revolution, Winnipeg and Buenos Aires boomed. An era of petro-geopolitics opened in Iran. China appeared to be awaking from its imperial slumber. Paris celebrated itself as the city of light — Berlin as the city of electricity.

Full of fascinating characters, stories, and insights, 1913: In Search of the World before the Great War brings a lost world vividly back to life, with provocative implications for how we understand our past and how we think about our future.

Genre:

-

"Emmerson draws upon an impressive range of contemporary source material, ranging from travel guides and memoirs to unpublished diaries, newspaper reports and diplomatic memos. They give a vivid portrait of the rapid changes occurring in daily life around the globe. Charles Emmerson captures all the world's hope and excitement as it experienced an economic El Dorado. 1913 is history without hindsight at its best."Wall Street Journal

-

"In each city the author vividly surveys the political, economic and cultural scenes. The effect is transporting; 1913 is both passport and time machine. The centenary of the Great War will no doubt see the publication of many fine histories of the conflict, but few are likely to paint so alluring a portrait of the world that was consumed by it-and that helped bring it about."Washington Post

-

"With the looming 100th anniversary of World War I, a spate of books about the not-so-Great War have begun to emerge. Emmerson's effort stands out for several reasons. First, Emmerson ranges widely, from Germany to Paris, from Bombay to Tokyo. Second, he is a sparkling writer, his narrative rarely flags and he has amassed a startling amount of detail."Daily Beast

-

"[Emmerson] aims not to explain what caused or was lost to the war, but to retrieve from the partial glare of hindsight the world in which it erupted. This is no modest undertaking. Mr. Emmerson draws from a wide range of sources, including memoirs, billboards and newspapers, to recreate a year that was fairly uneventful. Not unlike Marcel Proust's "In Search of Lost Time," the first instalments of which were published in 1913, his narrative finds coherence in the unremarkable. [W]hat emerges is a rich portrait and an important set of ideas."The Economist

-

"Emmerson offers an impressive sweep that marshals much detail along the way, though at times there is a sense of being on a historical package tour (Baedeker is, indeed, a frequently cited source) in which some city breaks are better rendered than others. But there are some gems. In the patchwork Austro-Hungarian empire, one could drive on both sides of the road and there were 10 official languages but no translators in parliament. Does anyone wonder that it fell apart?"Financial Times

-

"Marvelous. Emmerson, a scholar at Chatham House, a renowned London think tank, brilliantly avoids the inevitability trap in 1913. His panoramic depiction of the last year before the Great War permits us to see the world as it might have looked through contemporary eyes, in its full colour and complexity, with a sense of the future's openness. Emmerson is a superb guide and companion, whether inviting us to take a seat next to him in a favourite corner of a Viennese cafe or to survey tout Paris from the Eiffel Tower. In many ways, his book works as a time-travelogue--indeed, it frequently quotes contemporary tourist literature and travelers' accounts."Cleveland Plain Dealer

-

"An eye-opening demonstration of just how modern the supposedly premodern world was."Maclean's

-

"The book reveals a world both different from today's world, yet still familiar in many ways. It captures the year of 1913 in a way that is fascinating and revealing."Galveston Daily News

-

"Portraying the European capitals of the next year's belligerent countries, Emmerson strikes a cosmopolitan tone by noting social interconnections linking London to Paris to Berlin to Constantinople. Including stops in Tehran, Mexico City, Jerusalem, several U.S. cities, Shanghai, and Tokyo, Emmerson's historical world tour emotively captures the civilization soon to vanish in WWI."Booklist

-

"Emmerson's project would not be as compelling if he had simply focused on Europe, or on England and her colonies. The Great War was truly a global war, and the world of 1913 was truly a global society. In his book, Emmerson gives fair weight to societies around the world rather than presenting the year from a Eurocentric point of view."Christian Science Monitor

-

"A fascinating bird's-eye view of a landscape seen in what was the dying light of empire and on the brink of tragedy. An imaginatively conceived, thoroughly researched, and outstandingly written perspective that is highly recommended for both academic and general readers."Library Journal, STARRED review

-

"Charles Emmerson has written a book that contains much in the way of wistfulness, hope, bitterness, discord, assassinations, technological advancement, and enmity between nations and peoples. We may not ever fully know the reasons or reasoning behind the urge for war, and Charles Emmerson wisely does not bring them all out, but in 1913 his synthesis of the nervousness, striving, and strains in specific parts of the world give us a better understanding of the upheavals that led to the First World War."Bookslut

-

The Spectator (UK)

"A masterful, comprehensive portrait of the world at that last moment in its history when Europe was incontrovertibly the centre of the universe, and, within it, London, the centre of the world. Charles Emmerson's 1913 brilliantly rescues [history] from the shadow of a war that would toll the end of the Old World and leave its survivors repining the loss of a Golden Age that had never been." -

"An ambitious, subtle account of the way the world was going until the first world war changed everything."The Guardian

-

"This ambitious panorama of a world on the brink throws up comparisons which are constantly provocative and fascinating."Daily Mail (UK)

-

"Where Emmerson really scores is in the nuggets of detail and contemporary quotes that sparkle from these essays."The Express (UK)