Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

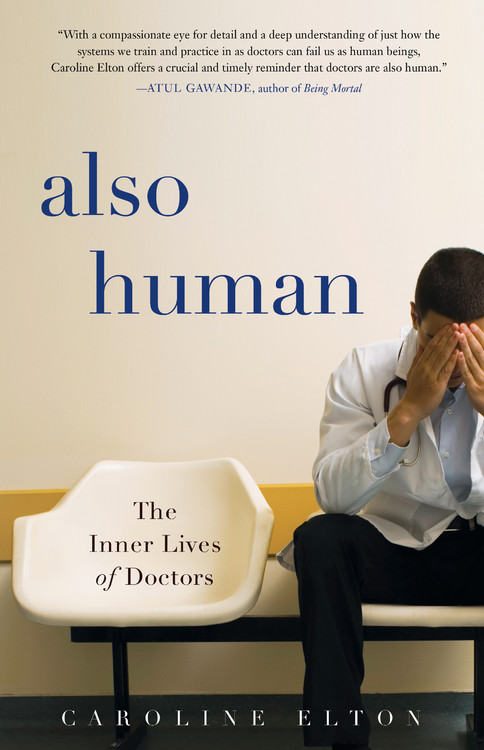

Also Human

The Inner Lives of Doctors

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 12, 2018

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465093731

Price

$32.00Price

$42.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $32.00 $42.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 12, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From ER and M*A*S*H to Grey’s Anatomy and House, the medical drama endures for good reason: we’re fascinated by the people we must trust when we are most vulnerable. In Also Human, vocational psychologist Caroline Elton introduces us to some of the distressed physicians who have come to her for help: doctors who face psychological challenges that threaten to destroy their careers and lives, including an obstetrician grappling with his own homosexuality, a high-achieving junior doctor who walks out of her first job within weeks of starting, and an oncology resident who faints when confronted with cancer patients. Entering a doctor’s office can be terrifying, sometimes for the doctor most of all. By examining the inner lives of these professionals, Also Human offers readers insight into, and empathy for, the very real struggles of those who hold power over life and death.

Genre:

-

"With a compassionate eye for detail and a deep understanding of just how the systems we train and practice in as doctors can fail us as human beings, Caroline Elton offers a crucial and timely reminder that doctors arealso human."Atul Gawande, author of Being Mortal

-

"Written with perceptive sympathy for the wounded healer, it is necessary reading for both doctors and patients."Hilary Mantel, Man Booker Prize-winning author of Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies

-

"Elton...passionately advocates for paying greater attention to the unique emotional needs of physicians."Health Affairs

-

"This important and much needed book describes the psychological difficulties of doctors in training and in practice and the woeful lack of support to them from teachers, colleagues, and institutions."LitMed

-

"Elton is particularly good on the subtle matters of gender and ethnic discrimination that punish doctors who are different from the white, male mainstream.... A useful adjunct to books from within medicine by the likes of Richard Selzer [and] Atul Gawande."Kirkus

-

"Elton, a vocational psychologist, spent the last 20 years observing, counseling, and helping very real, vulnerable, and wholly human people in the medical field.... Written in a welcoming style, this practical and helpful look at best medical practices will benefit patients, practitioners, and everyone else involved in health care."Booklist

-

"At a time when burnout and depression among doctors have reached epidemic proportions, Caroline Elton masterfully dissects the issues to explain how we arrived at this point. Ultimately, we must remember that doctors are Also Human and we need a comprehensive approach to uplift the emotional well-being of the medical workforce."Eric Topol, Executive Vice-President of Scripps Research Institute and author of The Patient Will See You Now

-

"At the heart of this book is the problem of how emotional resilience can be identified in prospective doctors and strengthened in practicing doctors. We are fallible human beings, not omniscient gods."Henry Marsh, Sunday Times (UK)

-

"A vivid, compelling account of how wounded healers may struggle to find healing. Elton has helped hundreds of doctors through crises in their personal and professional lives, and her stories read as an urgent manifesto to reform the caring professions--that they might begin to care for their own. With reference from the psychological literature, as well as her own extensive clinical experience, she examines why some doctors are overwhelmed by the pressures of medicine, while others may even thrive under them."Gavin Francis, physician and author of Adventures in Human Being and Shapeshifters

-

"Fascinating and troubling. Read it and weep."Susie Orbach, author of Fat Is a Feminist Issue

-

"Haunting, beautiful, and urgent."Johann Hari, author of Chasing the Scream and Lost Connections

-

"For patients and doctors alike, this book is required reading."Daily Mail (UK)

-

"[Elton's] description of the psychological forces underlying the ways doctors act--avoidance coping, intellectualization, suppression, repression--is fascinating."Literary Review (UK)