By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

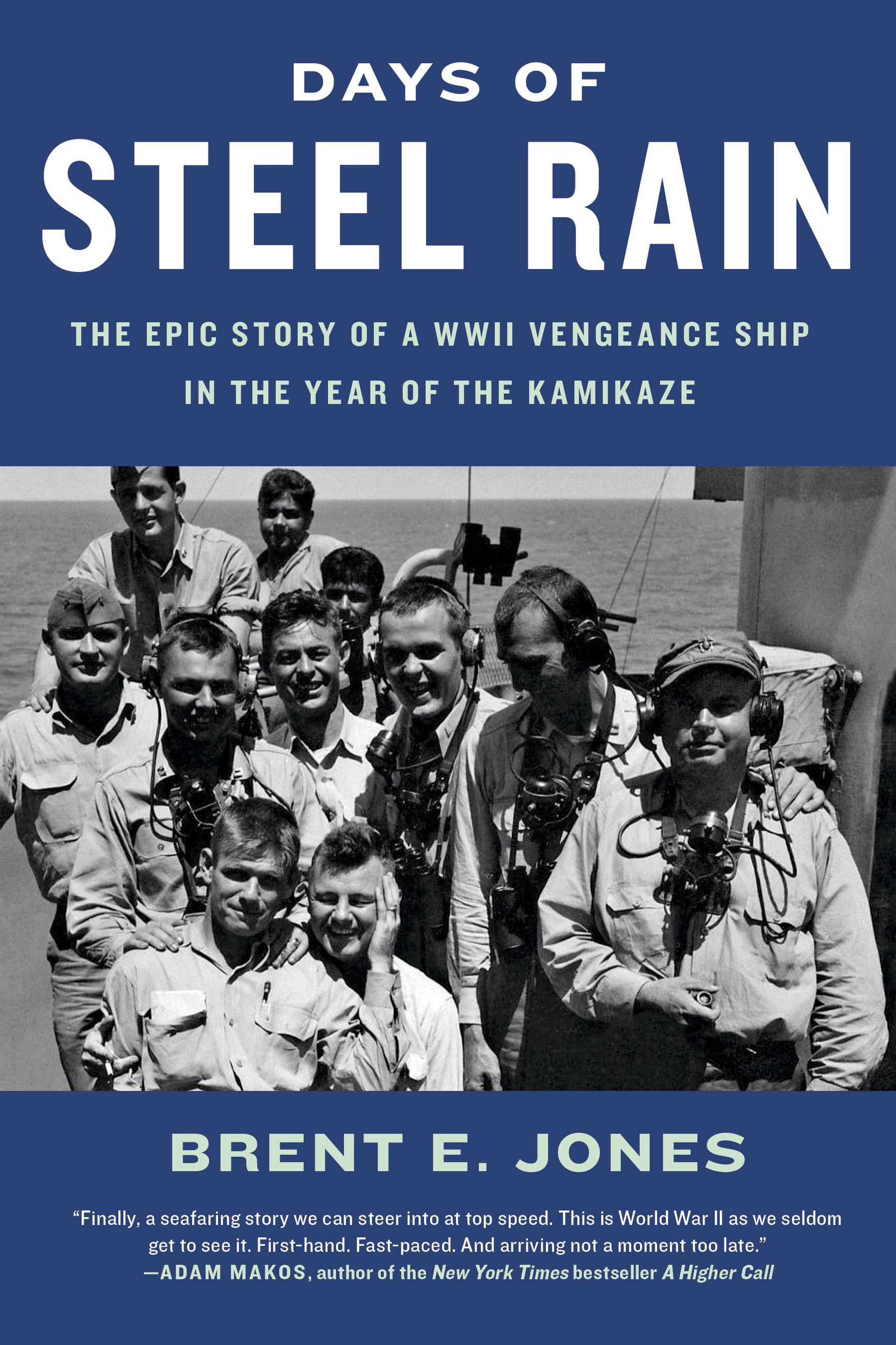

Days of Steel Rain

The Epic Story of a WWII Vengeance Ship in the Year of the Kamikaze

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 10, 2022

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316451086

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 10, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This intimate true account of Americans at war follows theepic drama of an unlikely group of men forced to work together in the face of an increasingly desperate enemy during the final year of World War II.

Sprawling across the Pacific, this untold story follows the crew of the newly-built “vengeance ship” USS Astoria, named for her sunken predecessor lost earlier in the war. At its center lies U.S. Navy Captain George Dyer, who vowed to return to action after suffering a horrific wound. He accepted the ship’s command in 1944, knowing it would be his last chance to avenge his injuries and salvage his career. Yet with the nation’s resources and personnel stretched thin by the war, he found that just getting the ship into action would prove to be a battle.Tensions among the crew flared from the start. Astoria‘s sailors and Marines were a collection of replacements, retreads, and older men. Some were broken by previous traumatic combat, most had no desire to be in the war, yet all found themselves fighting an enemy more afraid of surrender than death.

The reluctant ship was called to respond to challenges that its men never could have anticipated. From a typhoon where the ocean was enemy to daring rescue missions, a gallant turn at Iwo Jima, and the ultimate crucible against the Kamikaze at Okinawa, they endured the worst of the final year of the war at sea.

Days of Steel Rain brings to life more than a decade of research and firsthand interviews, depicting with unprecedented insight the singular drama of a captain grappling with an untested crew and men who had endured enough amidst some of the most brutal fighting of World War II. Throughout, Brent Jones fills the narrative with secret diaries, memoirs, letters, interpersonal conflicts, and the innermost thoughts of the Astoria men—and more than 80 photographs that have never before been published. Days of Steel Rain weaves an intimate, unforgettable portrait of leadership, heroism, endurance, and redemption.

Genre:

-

"Days of Steel Rain relates in graphic and dramatic detail how cruiser USS Astoria and her sailors withstood Japan's dreaded Kamikaze assaults during the most deadly [and] decisive campaigns of the Pacific War. A first-rate account of American courage, selfless sacrifice, and perseverance against high odds in the crucible of combat. A must-read for anyone interested in the battle history of U.S. Navy."Edward J. Marolda, former Senior Historian of the U.S. Navy

-

"Brent E. Jones strikes gold with his stirring Days of Steel Rain, which relates the exploits of his World War II relative, Lawrence Jones, and his shipmates aboard the light cruiser, USS Astoria, as they battle their foe off Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and Japan in the Pacific War's final year. Relying on vivid combat sequences, Jones has provided touching testimony that humans, not guns and weapons, win wars. He offers a fitting tribute to his relative and to the other courageous sailors who manned that cruiser."John Wukovits, author of Tin Can Titans and Dogfight Over Tokyo

-

"Finally, a seafaring story we can steer into at top speed. This is World War II as we seldom get to see it. First-hand.Fast-paced. And arriving not a moment too late. Batten down the hatches—you’re about to follow a fraternity of heroes as they plunge into chaos. It’s time to go to sea.”Adam Makos, author of the New York Times bestseller A Higher Call

-

“As powerfully built as the ship at its heart, Days of Steel Rain is a mighty feat of storytelling. Herein lie Iwo Jima bombardments, a near-collision with [the] Indianapolis, kamikazes, typhoons, and incomparable men. The narrative is vigorous, deeply felt .and so attentively wrought, it’s as if Brent E. Jones came through the war on Astoria herself.”James Sullivan, author of Unsinkable

-

"Truly an amazing story: the combat experiences of a single fighting ship as told through the actual words of the men at the time. The human condition--sights, sounds, reactions, worries, thoughts, words--is often overlooked and left out of most wartime histories. The eyewitness accounts and personal testimonies of the crew of Astoria--from Captain down to Seaman--make the Fast Carrier Task Force come alive in a vivid blaze of color, the roar of naval gunfire, a rolling and plunging deck underfoot, and the adrenaline of men alternately fighting to survive a typhoon or under vicious air attack. Not spared are the personal struggles with numbing routine split between tedium and boredom; fatigue laced with humor, sarcasm, endless rumors, and even fatalism. I particularly enjoyed the exciting stories of Chuck Tanner and his team of Kingfisher pilots; their incredible exploits, adventures and successful rescues-at-sea are the likes of which I've never read anywhere else up until now. In short, Days of Steel Rain brings alive a gallery of real people: some heroes and villains to be sure, but mostly average American boys and men, Bluejackets and Marines, caught in the crucible that was the western Pacific in 1945. It is an uncommonly related perspective indeed."Dominic DeScisciolo, Captain, U.S. Navy (Ret.)

-

"The story of how this novice crew came together over time under Dyer's firm, but fair, leadership to become a very tough, very competent crew capable of performing consistently and well under extraordinarily demanding conditions. A great story of a great ship!"Admiral John C. Harvey, Jr., USN (Ret.)

-

"A gripping...narrative...the reader is propelled into vivid battles across the Pacific, at Iwo Jima, and finally, Okinawa....An outstanding historical account of the human condition during wartime late in the Pacific War, written from the perspective of those who lived it...Americans at war and united to overtime despite their personal demons and feelings toward one another - under conditions they never dreamed they would face, let alone survive. The book needed to be written - to break their silence."North Texas Living

-

“Remarkably researched….Without preaching, this narrative shows how honor and respect are earned one decision at a time, often without knowledge of other factors that only become clear later."Seattle Book Review

-

"[Jones] describes individuals in an intimate fashion that will fascinate anyone interested in naval history."Proceedings magazine

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use