By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

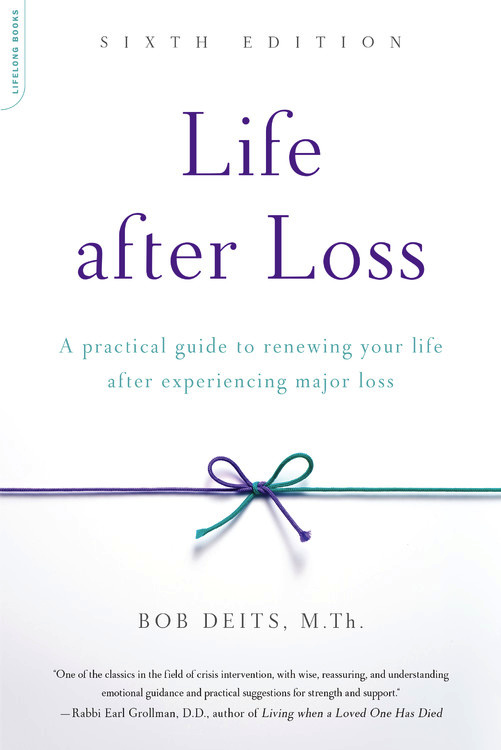

Life after Loss

A Practical Guide to Renewing Your Life after Experiencing Major Loss

Contributors

By Bob Deits

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 2, 2017

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Balance

- ISBN-13

- 9780738219615

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback (Revised) $19.99 $25.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 2, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

-

One of the classics in the field of crisis intervention, with wise, reassuring, and understanding emotional guidance and practical suggestions for strength and support.Rabbi Earl Grollman. D.D., author of Living when a Loved One Has Died

-

[A] roadmap for those in grief.Lawrence J. Lincoln, M.D., Staff, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross Center

-

A practical guide for those who have difficulty in finding their way back after profound ordeals....Highly valuable and compassionate.Norman Cousins, author of Anatomy of an Illness

-

Old grief is as important a work as new grief, and it resurfaces with brand new lessons....Sooner or later, a difficult journey will come knocking (again), igniting the grief process. No one should be without this brilliant healing toolbox of a book.Maryann Makekau, founder of Hope Matters and coauthor of When Your Grandma Forgets

-

Loss is a universal experience and too often, because they don't know what to say, well-meaning doctors, friends, and family say, 'Don't worry, you'll get over it.' We never get over a major loss but we can find a way through it to enjoy a full and fulfilling life. In Life after Loss, Bob Deits provides compassionate and practical advice for grieving and rebuilding a meaningful life after loss. As a palliative care physician, I care for people dealing with serious illness and those facing the end of life and their loved ones--where grief and loss are a constant presence. I will recommend this wise and important book as essential reading to all my patients and their families.Steven Z. Pantilat, MD, Kates-Burnard and Hellman Distinguished Professor of Palliative Care; Director, Palliative Care Program, UCSF; author of Life after the Diagnosis: Expert Advice on Living Well with Serious Illness for Patients and Caregivers

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use