Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

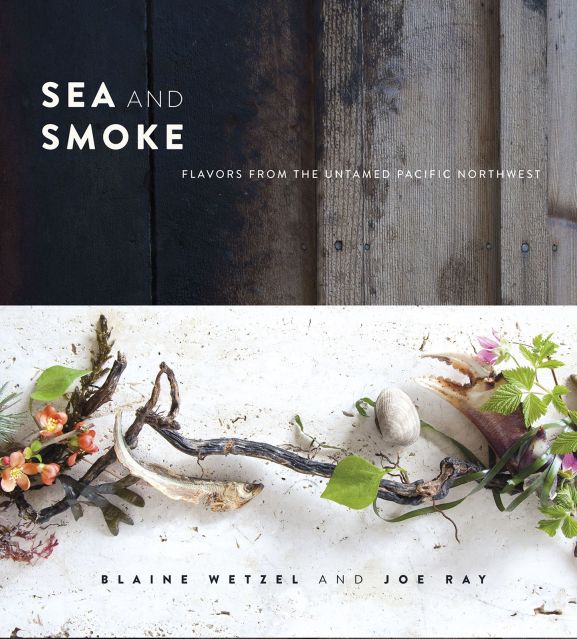

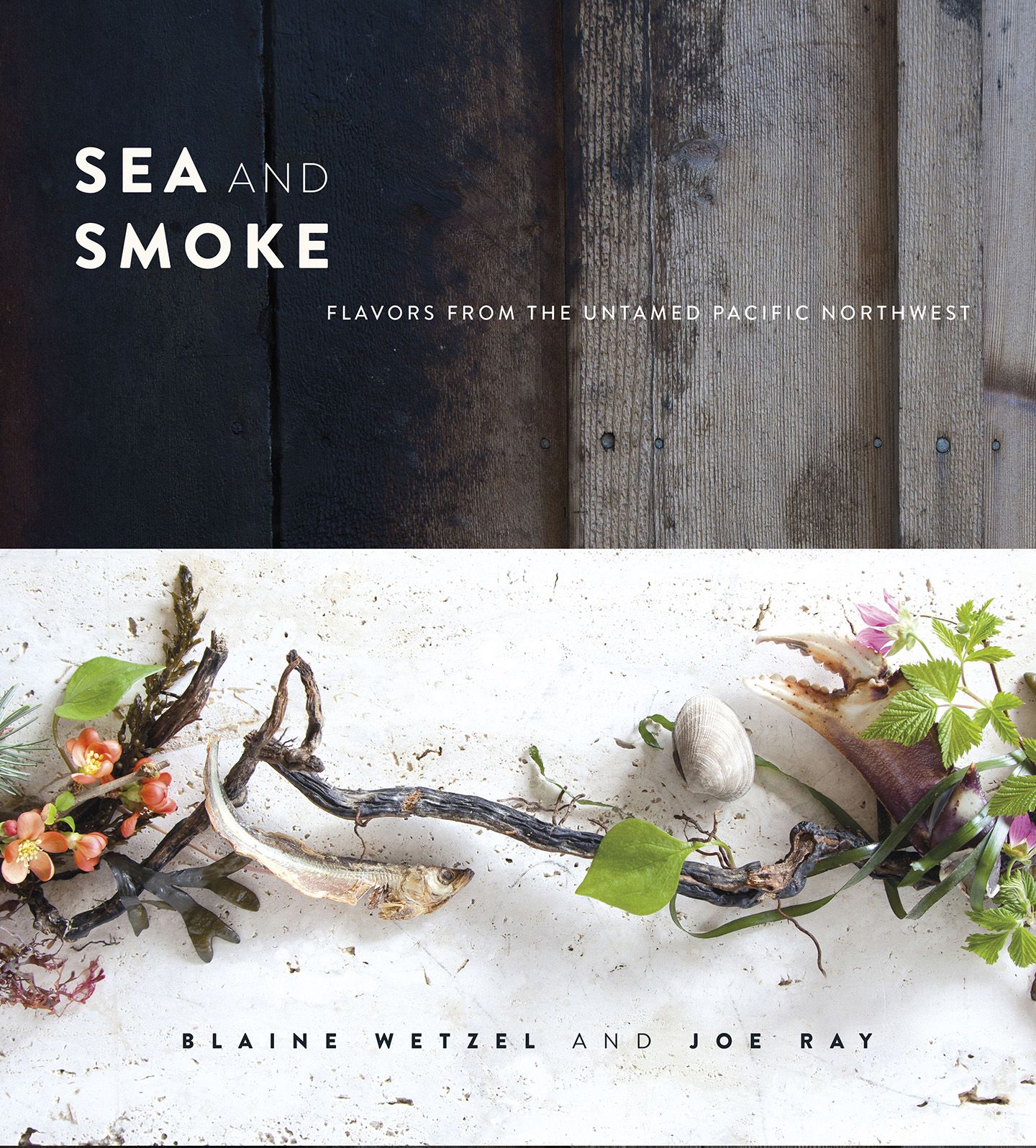

Sea and Smoke

Flavors from the Untamed Pacific Northwest

Contributors

By Joe Ray

Formats and Prices

Price

$22.99Price

$29.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $22.99 $29.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $52.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 27, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A native of the Pacific Northwest, two-time James Beard winning chef Blaine Wetzel saw Lummi Island, a rugged place with fewer than 1,000 residents off the coast of Seattle, as the ideal venue for his unique brand of hyperlocalism. Sea and Smoke is a culinary celebration of what is good, flavorful, and nearby, with recipes like Herring Roe on Kelp with Charred Dandelions and Smoked Mussels creating an intimate relationship between the food and landscape of the Pacific Northwest.

The smokehouse, the fisherman, and the farmer yield the ingredients for unforgettable meals at The Willows Inn, a reflection of Wetzel’s commitment both to locally-sourced ingredients and the sights, smells, and tastes of the foggy, coastal environment of Lummi Island. Award-winning journalist Joe Ray tells the tale of the Inn’s rise to stardom, documenting how all the pieces came together to make a reservation at Wetzel’s remote restaurant one of the most sought-after in the world.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 27, 2015

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762453115

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use