Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

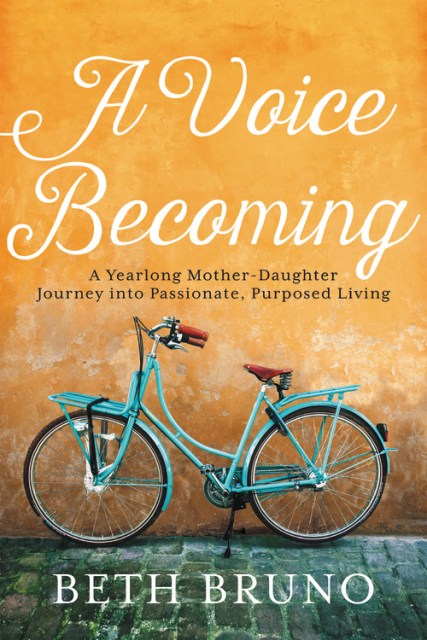

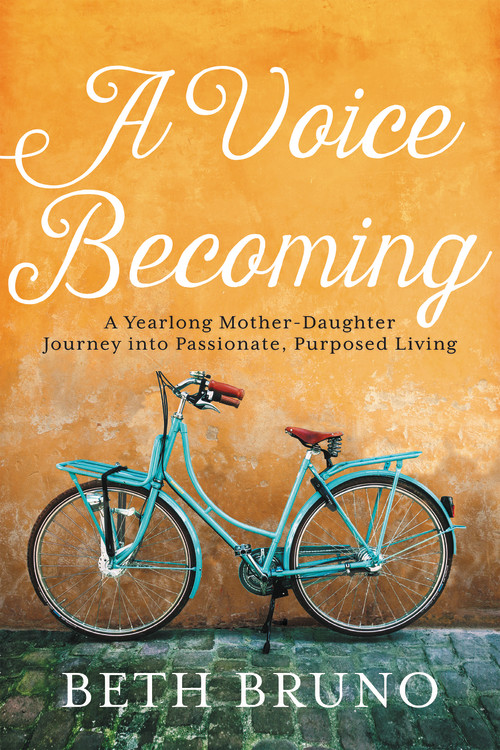

A Voice Becoming

A Yearlong Mother-Daughter Journey into Passionate, Purposed Living

Contributors

By Beth Bruno

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 31, 2018

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- FaithWords

- ISBN-13

- 9781478974673

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $11.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 31, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

What if you as a mother concentrated on your daughter for one year? Who might she become? A Voice Becoming is for moms who want to usher their daughters into womanhood but know they need more than tips, techniques, and programs. This is for moms who to desire to chart a course for their daughters that helps them know the story of God they are entering and the global sisterhood of women they are joining.

A Voice Becoming is written by a fellow sojourner, still in the middle of the journey, processing her own story as she casts a vision for her daughter to discover hers. Sometimes road maps are too restrictive and a friend is needed who has made the journey already. Beth Bruno seeks to activate moms by infusing them with hope and vision. Readers will join Beth in a yearlong journey of teaching their daughters that women lead, women love, women fight, women sacrifice, and women create. Moms learn how to use film and books, tangible experiences, volunteering, interviewing other women, traveling, and more in a creative and life-altering way to help solidify these important concepts in the mind and life of their young teen.

-

"An intensely intimate look into a mother's fight for her daughter's soul and purpose. The challenges of modern life and influences are no match for this intelligent and creative resource. Pulling from memoir, Biblical examples, literature, and real-life relationships, A VOICE BECOMING is decisively the resource for creating a life-changing rite of passage for your coming-of-age daughter."Shayne Moore, author and founder of Redbud Writers Guild

-

"Beth Bruno clearly has a heart for girls, and in this unique resource for mothers and daughters, she bridges the two generations. With wisdom, humility, and heartfelt confessions, Beth offers a road map on how to celebrate our adolescent daughters while helping them discover their voice and purpose. In an age of intentional parenting, where moms hunger for guidance on how to raise strong, confident, and godly girls, this book meets an important need. Taken to heart, it can strengthen both families and society for many years to come."Kari Kampakis, mother of four daughters and author of 10 Ultimate Truths Girls Should Know and Liked: Whose Approval Are You Living For?

-

"In her practical book, Beth Bruno helps mothers imagine their daughters' transition from girlhood to young adulthood differently, inspiring courage in place of fear, intentionality where there might otherwise be resignation. Besides offering wonderful recommendations of books and movies and activities to share together, Beth most importantly invites mothers into conversation and intimate relationship with their daughters. I only wish I'd read A VOICE BECOMING when my own two daughters were younger."Jen Pollock Michel, award-winning author of Teach Us to Want and Keeping Place

-

"Beth's book is a must read for mothers, grandmothers, aunts, as well as, fathers and grandfathers and uncles! I wish we had this guide raising our two daughters, but we now have two granddaughters and the role we play is far more active in promoting the strength, voice, and character of our girls. Both granddaughters have t-shirts that say: 'The future is feminine.' I believe this is true and there is no more important task than helping our granddaughters forge a future that is full of God and rich with the use of power for the glory of God. This guide is a gift for all those who believe in our children's and grandchildren's future."Dan B. and Rebecca Allender, Ph.D., founders of the Allender Center for Trauma and Abuse and Professor of Counseling Psychology, The Seattle School of Theology and Psychology