Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

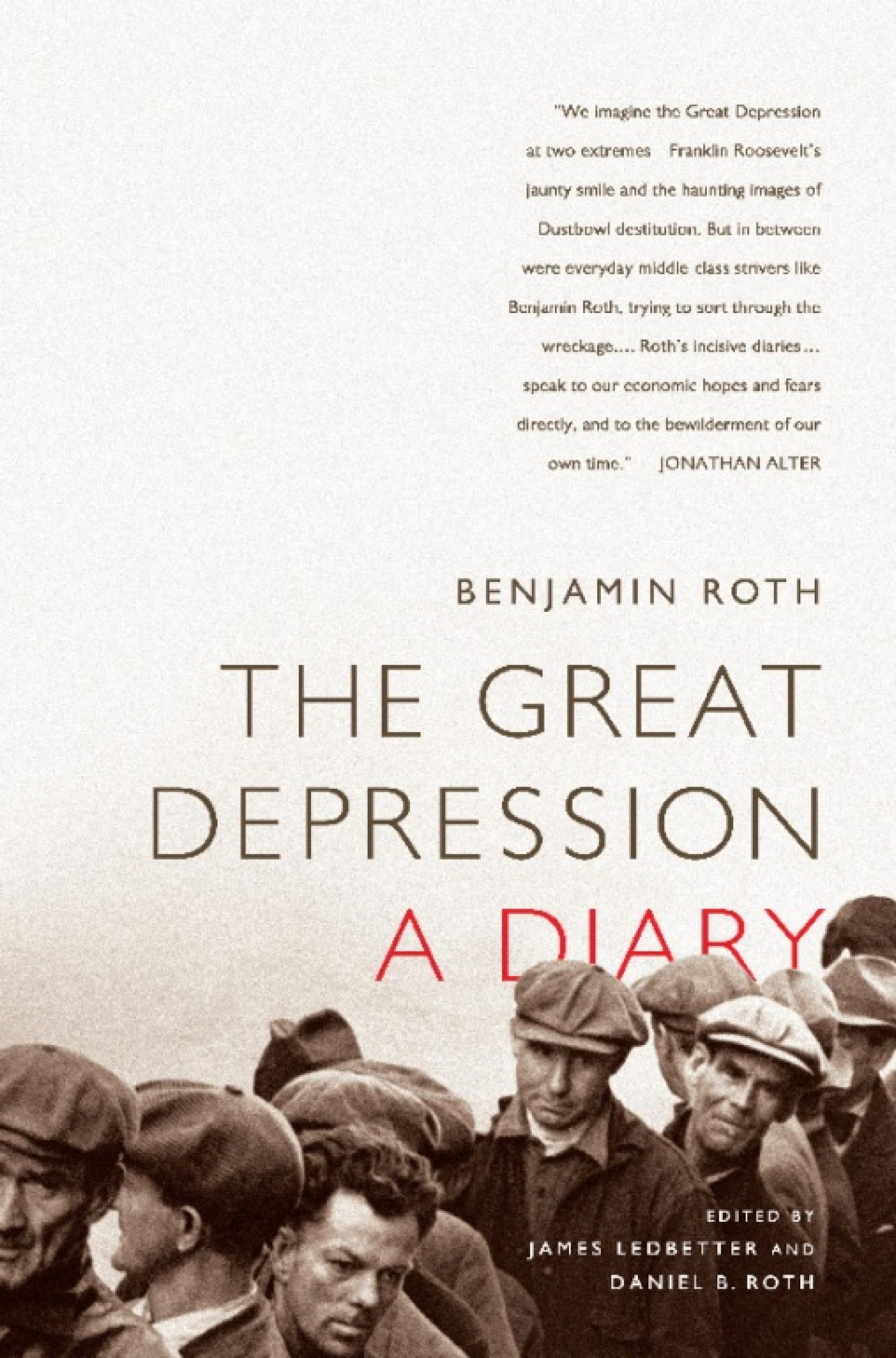

The Great Depression: A Diary

Contributors

Edited by James Ledbetter

Edited by Daniel B Roth

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 22, 2009

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586488376

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 22, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In the early 1920s, Benjamin Roth was a young lawyer fresh out of the army. He settled in Youngstown, Ohio, a booming Midwestern industrial town. Times were good—until the stock market crash of 1929. After nearly two years of economic crisis, it was clear that the heady prosperity of the Roaring Twenties would not return quickly.

As Roth began to grasp the magnitude of what had happened to American economic life, he set out to record his impressions in a diary—a document that would grow to span several volumes over more than a decade. Penning brief, clear-eyed notes on the crisis which unfolded around him, Roth struggled to understand the complex forces governing political and economic life, yet he remained eager to learn from the crisis. As he wrote of what is now known as the Great Depression, "To the man past middle life it spells tragedy and disaster, but to those of us in the middle thirties it may be a great school of experience out of which some worth while lesson may be salvaged."

Roth's words from that unique time seem to speak directly to readers today. His perceptions and experiences have a chilling similarity to those of our own era. Fearful of inflation and skeptical of big government, Roth yearned for signs of true recovery, and eventually formed his own theories of how a prudent person might survive hard times. The Great Depression: A Diary, edited by James Ledbetter, editor of Slate's "The Big Money," and Roth's son, Daniel B. Roth, reveals another side of the Great Depression—one lived through by ordinary, middle-class folks, who on a daily basis grappled with a swiftly changing economy coupled with anxiety about the unknown future.

Genre:

-

“Mr. Roth’s diaries … are compelling reading, because they force readers to reflect on both the similarities and the differences between then and now…. We’re all a little like Benjamin Roth, asking questions we don’t know the answer to, and wonder, as he did 70 years ago, whether the crisis is, indeed, over.”The New York Times

-

“[Roth’s] entries compellingly detail the everyday.”Financial Times

-

“Benjamin Roth has left us a vivid portrait of the Great Depression that is all the more powerful for the similarities and differences with the financial upheavals of today. Roth enables us -- in ways no historian can match -- to immerse ourselves in the sense of despair that Americans of that era felt and their hope that the economy would revive, long before it did. To read the diaries now is both enlightening and chilling.”Charles R. Morris, The Trillion Dollar Meltdown

-

“We imagine the Great Depression at two extremes--Franklin Roosevelt's jaunty smile and the haunting images of Dustbowl destitution. But in between were everyday middle class strivers like Benjamin Roth, trying to sort through the wreckage. FDR and the WPA may be long gone but the professional class remains, and the record of its struggle in the Depression has been thin until now. Roth's incisive diaries are more than a precious time capsule. They speak to our economic hopes and fears directly, and to the bewilderment of our own time."Jonathan Alter, The Defining Moment: FDR’s Hundred Days and the Triumph of Hope

-

“Here are brief, unsentimental, clear-eyed notes of the growing sense of hopelessness that came over Midwestern American life. This moving book is edited by [Roth’s] son Daniel.”Spectator Business (UK)

-

“A fascinating read, and strangely familiar.”MoneySense

-

“Roth’s diary is plainly written and professionally edited. It is a window on another age.”The Seattle Times

-

“There is an honest searching quality to his day-by-day accounts of banks closing, bread lines forming, friends failing. Striving to understand, he provides a remarkable and often engagingly literate discussion of the great Depression’s impact on people like him.”Minneapolis Star-Tribune