By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

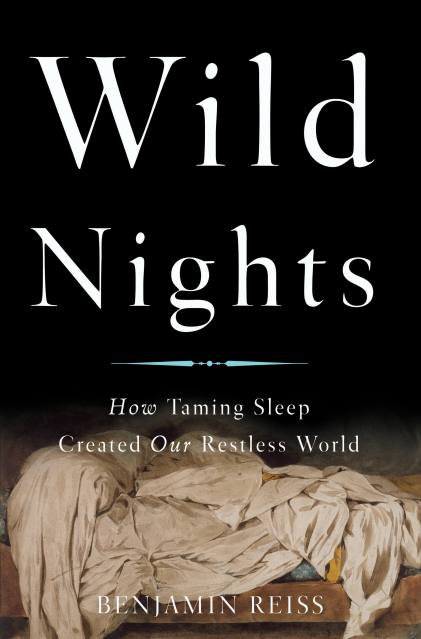

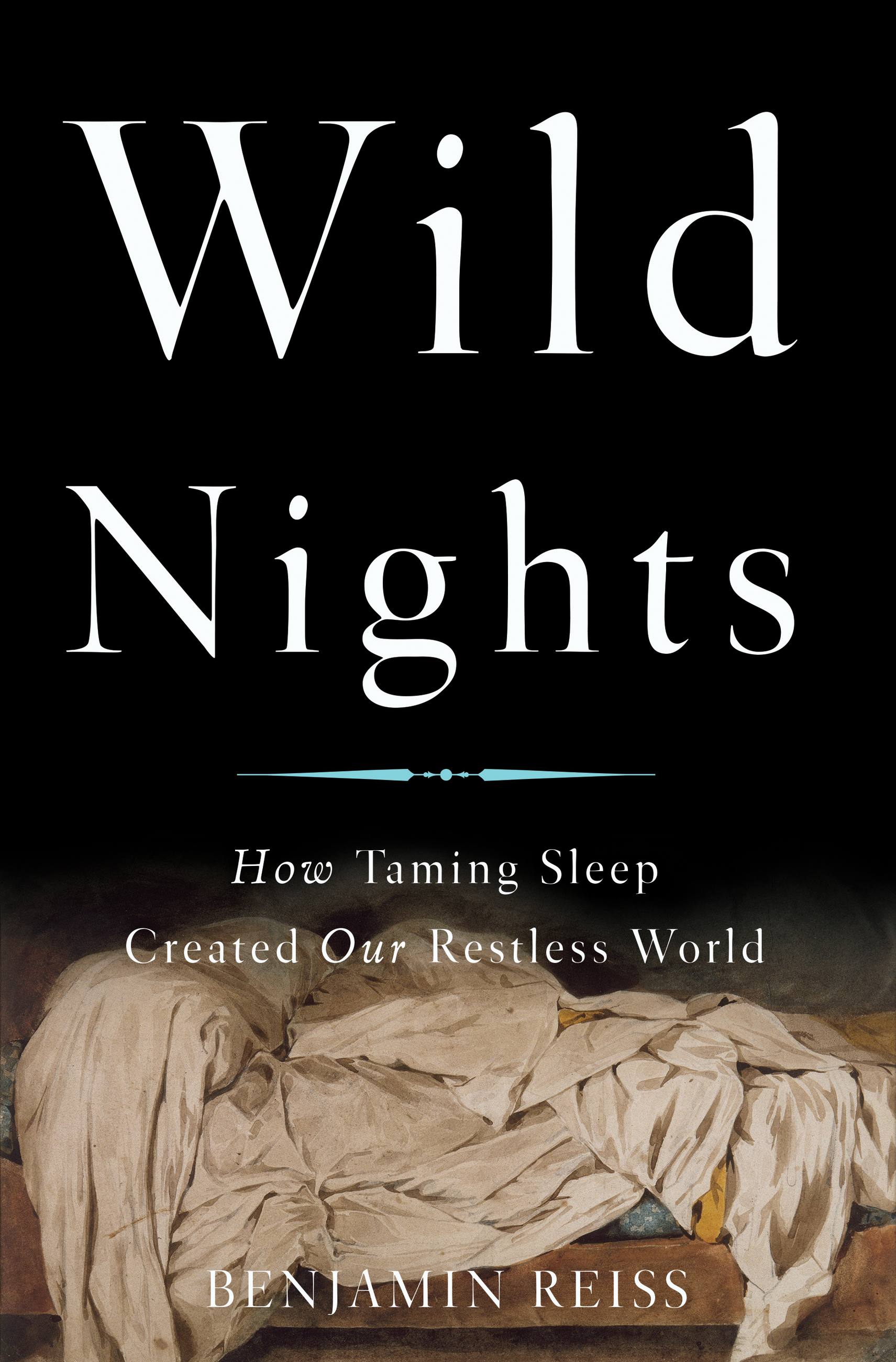

Wild Nights

How Taming Sleep Created Our Restless World

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 7, 2017

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465061952

Price

$28.00Price

$36.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 7, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Why is sleep frustrating for so many people? Why do we spend so much time and money managing and medicating it, and training ourselves and our children to do it correctly? In Wild Nights, Benjamin Reiss finds answers in sleep’s hidden history — one that leads to our present, sleep-obsessed society, its tacitly accepted rules, and their troubling consequences.

Today we define a good night’s sleep very narrowly: eight hours in one shot, sealed off in private bedrooms, children apart from parents. But for most of human history, practically no one slept this way. Tracing sleep’s transformation since the dawn of the industrial age, Reiss weaves together insights from literature, social and medical history, and cutting-edge science to show how and why we have tried and failed to tame sleep. In lyrical prose, he leads readers from bedrooms and laboratories to factories and battlefields to Henry David Thoreau’s famous cabin at Walden Pond, telling the stories of troubled sleepers, hibernating peasants, sleepwalking preachers, cave-dwelling sleep researchers, slaves who led nighttime uprisings, rebellious workers, spectacularly frazzled parents, and utopian dreamers. We are hardly the first people, Reiss makes clear, to chafe against our modern rules for sleeping.

A stirring testament to sleep’s diversity, Wild Nights offers a profound reminder that in the vulnerability of slumber we can find our shared humanity. By peeling back the covers of history, Reiss recaptures sleep’s mystery and grandeur and offers hope to weary readers: as sleep was transformed once before, so too can it change today.

Genre:

-

"What makes Wild Nights so liberating is that it is descriptive, not prescriptive. It does not hector...It aims, rather, to describe the social history and evolving culture of sleep--through literature, through ethnographies, through old diaries and memoirs and medical texts... [Wild Nights] pops with insight."--Jennifer Senior, New York Times

-

"[Wild Nights] is a new cultural and anthropological examination of sleep through the ages.... Sleep remains a universal experience, but it's lived seven billion different ways. One finishes Wild Nights with the feeling that our modern-day anxieties about sleep are the symptom of another, more complicated disease."Jacob Silverman, New Republic

-

"Sleep is a culturally fluid phenomenon, reveals Benjamin Reiss in this marvelous scientific and literary study."Nature

-

"Western society is obsessed with a good night's sleep. To get it, we impose strict prebed rituals and regular wake-up times on ourselves and our children, feeling anxious if we toss and turn in the night. But the idea of a perfect sleep practice is relatively new in human history, Benjamin Reiss explains in his new book Wild Nights."Sarah Begley, TIME

-

"Get a solid eight hours in, no electronic screens in bed, wake up at the same time every morning, yeah, yeah. We modern fold have it all figured out, don't we? Maybe not, says Reiss, as he explores how getting a good night's sleep evolved and why it varies from one culture and era to the next."Gemma Tarlach, Discover

-

"In his book on the mysteries of human sleep, [Reiss] looks for guidance to the latest scientific studies, yes, but he also ventures beyond the realm of the scientific, including insights from history and literature."Science of Us

-

"[Wild Nights is] a great, collective blend of scientific, historical, and literary works that is as well-written and enjoyable as it is provocative and informative.... Undoubtedly, this book is an important contribution for everyone who sleeps, scientists and other citizens alike."Sleep Health Journal

-

"[Wild Nights] is a captivating examination and Reiss gives readers much to ponder long into the night."Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

"[Wild Nights is] a thorough probing into why sleep is such a problem for so many in contemporary society.... A fresh approach to a familiar phenomenon."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Reiss's interdisciplinary approach to the topic offers varied perspectives, compelling anecdotes, and a well-researched bibliography for readers interested in learning more about the global state of sleep affairs."Library Journal

-

"Engaging our imagination with equal parts history, literature, science, and social criticism, Benjamin Reiss traces our past notions of sleep, from sources as diverse as Thoreau's journals, Balzac's coffee consumption, and Skinner's baby box, to illumine our present views--potentially to transform them."Maryanne Wolf, author of Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain

-

"Wild Nights is a literary and historical triumph, showing how sleep patterns have been deeply connected to social structures throughout human history. It is a profound and thoroughly readable book."Carlos H. Schenck, M.D., author of Sleep: The Mysteries, The Problems, The Solutions

-

"Lacking for neither flair nor wit, Reiss shows how deeply embedded sleep, in all of rich complexity, has been in the American past. Wild Nights is nothing short of a tour de force."A. Roger Ekirch, author of At Day's Close: Night in Times Past

-

"A fascinating look at a phenomenon we have taken for granted. Benjamin Reiss pulls the bedcovers off of sleep, revealing a deep and significant history of Western culture and politics.... Written with subtlety and provocation, this is a must-read for anyone whose head ever hit a pillow."Lennard J. Davis, author of Enabling Acts and Obsession: A History

-

"Ranging widely across time and cultures, Wild Nights offers a rich perspective on Americans' present-day expectations about a good night's sleep.... This smart and engaging book is an ideal companion for that middle-of-the-night break, as well as for serious thought in the bright light of day."Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, author of A Taste for Provence and Wild Unrest

-

"A lively, astute, wide-ranging reconnaissance of the attempted re-engineering of modern humanity's sleep habits. Benjamin Reiss pointedly and persuasively questions whether today's 'sleep science' delivers better results than what seemed second nature to our pre-industrial forebears."Lawrence Buell, Harvard University