By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

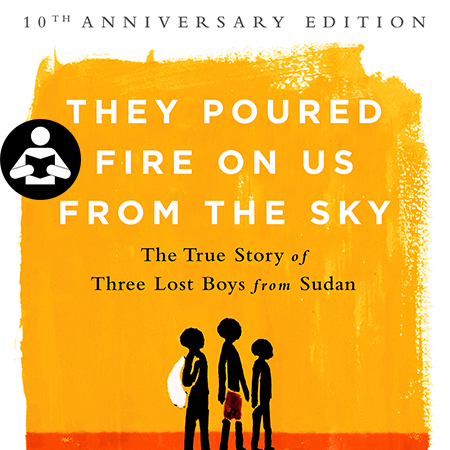

They Poured Fire on Us From the Sky

The Story of Three Lost Boys from Sudan

Contributors

By Benson Deng

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 11, 2015

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610395991

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback (Revised) $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 11, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“A moving, beautifully written account, by turns raw and tender.” —Los Angeles Times

A Washington Post Best Book of the Year

Between 1987 and 1989, Alepho, Benjamin, and Benson, like tens of thousands of young boys, took flight from the massacres of Sudan's civil war. They became known as the Lost Boys. With little more than the clothes on their backs, sometimes not even that, they streamed out over Sudan in search of refuge. Their journey led them first to Ethiopia and then, driven back into Sudan, toward Kenya. They walked nearly one thousand miles, sustained only by the sheer will to live.

They Poured Fire on Us From the Sky is the three boys' account of that unimaginable journey. With the candor and the purity of their child's-eye-vision, Alephonsion, Benjamin, and Benson recall by turns: how they endured the hunger and strength-sapping illnesses-dysentery, malaria, and yellow fever; how they dodged the life-threatening predators-lions, snakes, crocodiles and soldiers alike-that dogged their footsteps; and how they grappled with a war that threatened continually to overwhelm them. Their story is a lyrical, captivating, timeless portrait of a childhood hurled into wartime and how they had the good fortune and belief in themselves to survive.

Genre:

-

A Los Angeles Times Bestseller

-

A Washington Post Best Book of the Year

-

Christopher Award Winner for Adult Books

-

Peacemaker Award Winner

-

“Tender and lyrical... One of the most riveting stories ever told of African childhoods—and a stirring tale of courage... Anyone interested in Africa, its children or the human will to survive should read this book. This beautifully told volume will remain on my desk for years to come.”The Washington Post

-

“A moving, beautifully written account, by turns raw and tender.”Los Angeles Times

-

“[The authors’] accounts, written first in lesson books and then on computer have been skillfully put together in a narrative, each boy carrying both history and that of their joint flight and reunion forward. The result is both fascinating and immediate, not least because of the guilelessness of the language and the particularly African use of metaphor and imagery. They Poured Fire on Us From the Sky conjures up a world of marabou storks, acacia trees, termite mounds taller than men, scorpions and snakes that move in the dark, a world governed by traditions, rituals, seasons, weather, and obligations.”New York Review of Books

-

“Their words speak for those who no longer have a voice. Their story will take the reader on a trip not soon forgotten of spirits unwilling to be broken.”San Antonio Express-News

-

“Their serious tone, broken by the occasional wry smile, memorializes their parents, the land and animals that wove the tapestry of their early childhoods. One reviewer called the book ‘deceptively understated.’ But the soft plainness of the young writers’ voices, combined with their moral insight, throws the surreal danger and strife into sharp relief.”San Diego Union-Tribune

-

“[They Poured Fire] is an amazing account of boys who managed to survive a terrifying ordeal. There's a kind of haunting beauty to their story. After reading this book, readers may feel like they’ve been on an adventure or in hell, depending on your point of view. Whatever the case, this book is an eye-opener.”Rocky Mountain News

-

“Lovely and unusual. Vital stories that can help readers understand events in Sudan on a human level. But They Poured Fire on Us From the Sky is no mere historical document; it is a wise and sophisticated examination of the arbitrary cruelties and joys of being alive.”Star Tribune

-

“[The] book is at once an important addition to the contemporary dialog on world affairs and a surprisingly lyrical account of coming of age under adverse conditions. These folkloric memories replete with lions and circumcision rituals describe a world centuries removed from the high-tech industrialization of Western society. But they years of war also have bestowed wisdom, and simple observations of childhood are seen now through different eyes.”Minneapolis Star-Tribune

-

“[The book] represent[s] genuine, heartfelt examples of what war does to young people and how they may adjust to life outside the country of their birth, especially the social and intellectual problems they experience.”Deseret Morning News

-

“In a harrowing account of the war, three young refugees in California remember how they were driven from their homes in Southern Sudan in the ethnic and religious conflicts that have left two million dead. They tell their stories quietly with the help of their mentor, coauthor Judy Bernstein, in clear, interwoven, narratives that put a personal face on statistics.”Booklist

-

“Well written, often poetic essays... This collection is moving in its descriptions of unbelievable courage.”Publishers Weekly

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use