Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

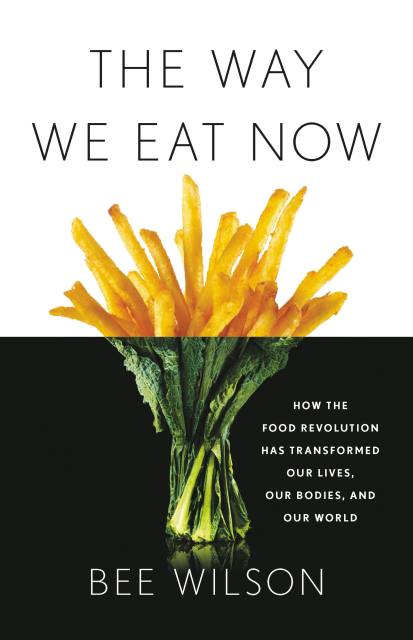

The Way We Eat Now

How the Food Revolution Has Transformed Our Lives, Our Bodies, and Our World

Contributors

By Bee Wilson

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 7, 2019

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465093984

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 7, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

An award-winning food writer takes us on a global tour of what the world eats–and shows us how we can change it for the better

Food is one of life’s great joys. So why has eating become such a source of anxiety and confusion?

Bee Wilson shows that in two generations the world has undergone a massive shift from traditional, limited diets to more globalized ways of eating, from bubble tea to quinoa, from Soylent to meal kits.

Paradoxically, our diets are getting healthier and less healthy at the same time. For some, there has never been a happier food era than today: a time of unusual herbs, farmers’ markets, and internet recipe swaps. Yet modern food also kills–diabetes and heart disease are on the rise everywhere on earth.

This is a book about the good, the terrible, and the avocado toast. A riveting exploration of the hidden forces behind what we eat, The Way We Eat Now explains how this food revolution has transformed our bodies, our social lives, and the world we live in.