By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

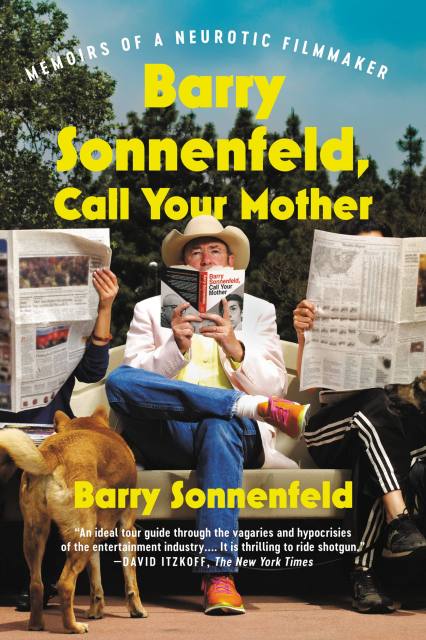

Barry Sonnenfeld, Call Your Mother

Memoirs of a Neurotic Filmmaker

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 14, 2021

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316415620

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 14, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

**A New York Times Editor’s Choice selection!**

This outrageous and hilarious memoir follows a film and television director’s life, from his idiosyncratic upbringing to his unexpected career as the director behind such huge film franchises as The Addams Family and Men in Black.

Written with poignant insight and real-life irony, the book follows Sonnenfeld from childhood as a French horn player through graduate film school at NYU, where he developed his talent for cinematography. His first job after graduating was shooting nine feature length pornos in nine days. From that humble entrée, he went on to form a friendship with the Coen Brothers, launching his career shooting their first three films.

Though Sonnenfeld had no ambition to direct, Scott Rudin convinced him to be the director of The Addams Family. It was a successful career move. He went on to direct many more films and television shows. Will Smith once joked that he wanted to take Sonnenfeld to Philadelphia public schools and say, “If this guy could end up as a successful film director on big budget films, anyone can.” This book is a fascinating and hilarious roadmap for anyone who thinks they can’t succeed in life because of a rough beginning.

-

"[Sonnenfeld's] moments of self-effacement...make him an ideal tour guide through the vagaries and hypocrisies of the entertainment industry.... He catalogs his own anxieties at length, sometimes to exorcise them and sometimes to fetishize them.... It is thrilling to ride shotgun."David Itzkoff, The New York Times

-

"If I went to prison, and I saw that Barry Sonnenfeld was going to be my cellmate, I would think, 'Oh, this will be a breeze.'"Jerry Seinfeld

-

"The extraordinary thing about Barry is how many truly strange and amazing chapters he's had in his life."Neil Patrick Harris

-

"Writing a book this sharp, [Sonnenfeld is] puncturing the myth of the Director as God....A wild account of his life and times....Here we have not only a new entrant in the movie-director memoir genre but an even rarer beast: a book by someone in the entertainment industry who is neither self-aggrandizing nor self-important but uniquely, and painfully, candid."The Wall Street Journal

-

"Hilarious."Ryan Seacrest, "Live with Kelly and Ryan"

-

“An engaging storyteller…. In his memoir, Sonnenfeld is both hilarious and tragic…. Somehow the combination works: Sonnenfeld’s breezy style engages us and makes us believe, as Will Smith has joked, that if Barry Sonnenfeld can be a director, anyone can.”Jeremy Hobson, NPR's "Here and Now"

-

"Barry's memoir is amazingly honest and brazenly hilarious. Now excuse me, I need to take a shower and try to get some of those images out of my head."Cheryl Hines

-

"Sonnenfeld's autobiography is laced with funny, sometimes absurd, moments.WBUR

-

"Anyone who has encountered Barry for any length of time has wondered how he came to be the way he is. The answer is hilariously, poignantly, and forthrightly told through various stories that resulted in me feeling nauseous, laughing out loud, blushing, and repeatedly saying under my breath, 'Oh my God, Barry.' Sometimes all of those things at once."Allison Williams

-

"Barry Sonnenfeld's memoir is not unlike many of his films. It's an incredible story about an unlikely hero. There is action, adventure, comedy, horror-and just a little bit of porn."Kelly Ripa

-

"Hilarious, full of heart, and there are no typos."Max Greenfield

-

"I couldn't put it down."Marc Maron

-

"The most purely enjoyable memoir I've ever read. The content of this neurotic genius's life is fascinating, complimented by his rare gift of storytelling."Patrick Warburton

-

"Exactly everything a good memoir should be."Audible Editorial

-

"Outrageous and hilarious...written with poignant insight and real-life irony."KATU AM Northwest

-

"Very funny...Told in his unmistakable voice."WAMC

-

"A neurotic, revelatory treat...[Sonnenfeld] spins eye-opening yarns....It's brutally honest...memorable and hilarious."HollywoodInToto.com

-

"His utter lack of sentiment when it comes to his achievements makes for a tonic against the typical showbiz-dreamer's success story. It is also a very, very funny book....Sonnenfeld is a portraitist with an ironic sense of humour some would call quintessentially Jewish, and he can't help but find the humanity and hilarity in the horrorshows...uniquely insightful."Film Freak Central

-

"Hilarious."Atlanta Jewish Times

-

"An extremely Jewy memoir."Jewish Telegraphic Agency

-

"Funny, wry, and thoroughly entertaining memoir. Sonnenfeld is, above all, a storyteller."Bookpage

-

"A candid, sometimes dark, entertaining, anecdotal trip down memory lane from a Hollywood icon."Booklist

-

"Sonnenfeld makes his debut as a memoirist with a brisk, funny recounting of his improbable rise to fame in the movie world...Zesty anecdotes about family, marriage, and fatherhood combine with Hollywood gossip to make for an entertaining romp."Kirkus Reviews

-

"The voice of Barry Sonnenfeld, Call Your Mother is one for this moment...chock full of humor and pathos."The Jewish News

-

"A very engaging read."Everyday Decisions with Jo Firestone

-

"His powers of exposition are impressive....This is both a serious and a comical book--sort of like Sophie's Choice, only funnier."The East Hampton Star

-

"Sonnenfeld leavens his many struggles with a substantial dose of humor. He might have endured much, but Barry Sonnenfeld, Call Your Mother: Memoirs of a Neurotic Filmmaker reveals Sonnenfeld to be a survivor. It's also a testament to how the rivers of fate can push you in unexpected directions....Sonnenfeld comes up with a wealth of entertaining stories....Revel in the ruminations of a man whose youthful traumas seared but didn't scar him."Book & Film Globe

-

"Amazing."Peter Sagal, NPR's "Wait Wait... Don't Tell Me"

-

"One of the funniest books I've ever read in my life."Holly Firfer, CNN First Reads

-

"Insightful and entertaining."IndieWire

-

“A perfect juicy read.”CafeMom

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use