Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

The Capitalist Comeback

The Trump Boom and the Left's Plot to Stop It

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $23.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 24, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

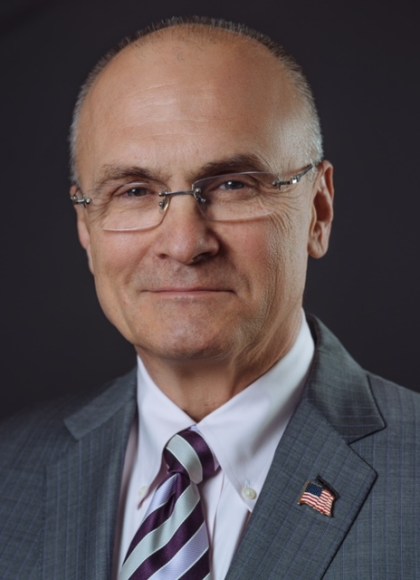

As a successful CEO in the restaurant industry, Andy Puzder uniquely understands how important the profit motive is to our country’s ultimate prosperity. Furthermore, as the grandson of immigrants, the son of a car salesman, and someone who worked his way up from earning minimum wage to running an international business, he has a first-hand view of how America’s exceptional capitalist spirit can lift everyone to success.

In 2016, the American people faced a stark choice between two very different presidential candidates. Hillary Clinton spent most of her adult life involved in politics and promised to uphold and advance the progressive legacy of President Barack Obama who had first won the White House on promises to “spread the wealth around.” Donald Trump, on the other hand, came from the business world, was an unapologetic capitalist, used his own personal wealth as inspiration, and promised simply to “Make America Great Again.”

By choosing Trump over Clinton, the American people put a stop to decades of government expansion under progressive leadership, and they might just have saved our economy by doing so.

America was once a land where everyone was encouraged to seek their fortune – the more prosperous our citizens, the more our whole society could in turn prosper. But leftist forces in the United States have been seeking to tarnish the pursuit of prosperity and to paint profit as an evil motivation fit only for greedy plutocrats. Andrew Puzder understands this first-hand after a progressive smear campaign stopped him from joining President Trump’s cabinet. As Puzder explains in his new book, The Capitalist Comeback, this was an act of desperation from a left wing facing irrelevance with a pro-business president in the White House. From its roots in the Progressive Era to labor unions to education to entertainment to its political resurgence with avowed socialist candidates such as Bernie Sanders, Puzder traces the development of the anti-profit forces in the United States and shows how, under President Trump, they can be vanquished for good.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 24, 2018

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781478975427

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use