Promotion

25% off sitewide. Make sure to order by 11:59am, 12/12 for holiday delivery! Code BEST25 automatically applied at checkout!

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

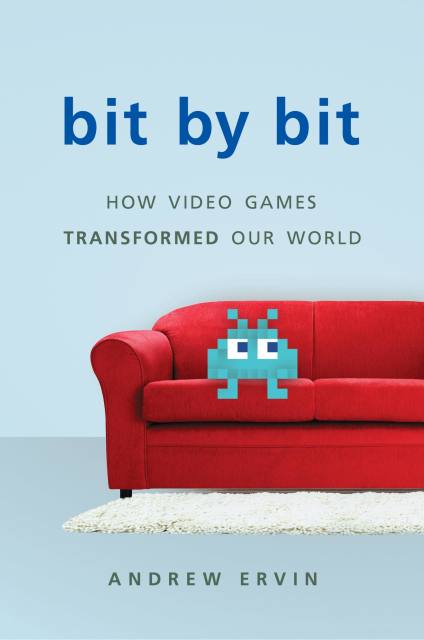

Bit by Bit

How Video Games Transformed Our World

Contributors

By Andrew Ervin

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 2, 2017

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465096589

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 2, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Video games have seemingly taken over our lives. Whereas gamers once constituted a small and largely male subculture, today 67 percent of American households play video games. The average gamer is now thirty-four years old and spends eight hours each week playing — and there is a 40 percent chance this person is a woman.

In Bit by Bit, Andrew Ervin sets out to understand the explosive popularity of video games. He travels to government laboratories, junk shops, and arcades. He interviews scientists and game designers, both old and young. In charting the material and technological history of video games, from the 1950s to the present, he suggests that their appeal starts and ends with the sense of creativity they instill in gamers. As Ervin argues, games are art because they are beautiful, moving, and even political — and because they turn players into artists themselves.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use