By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

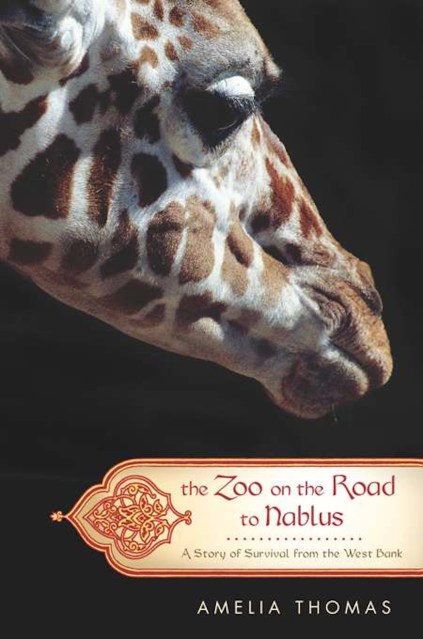

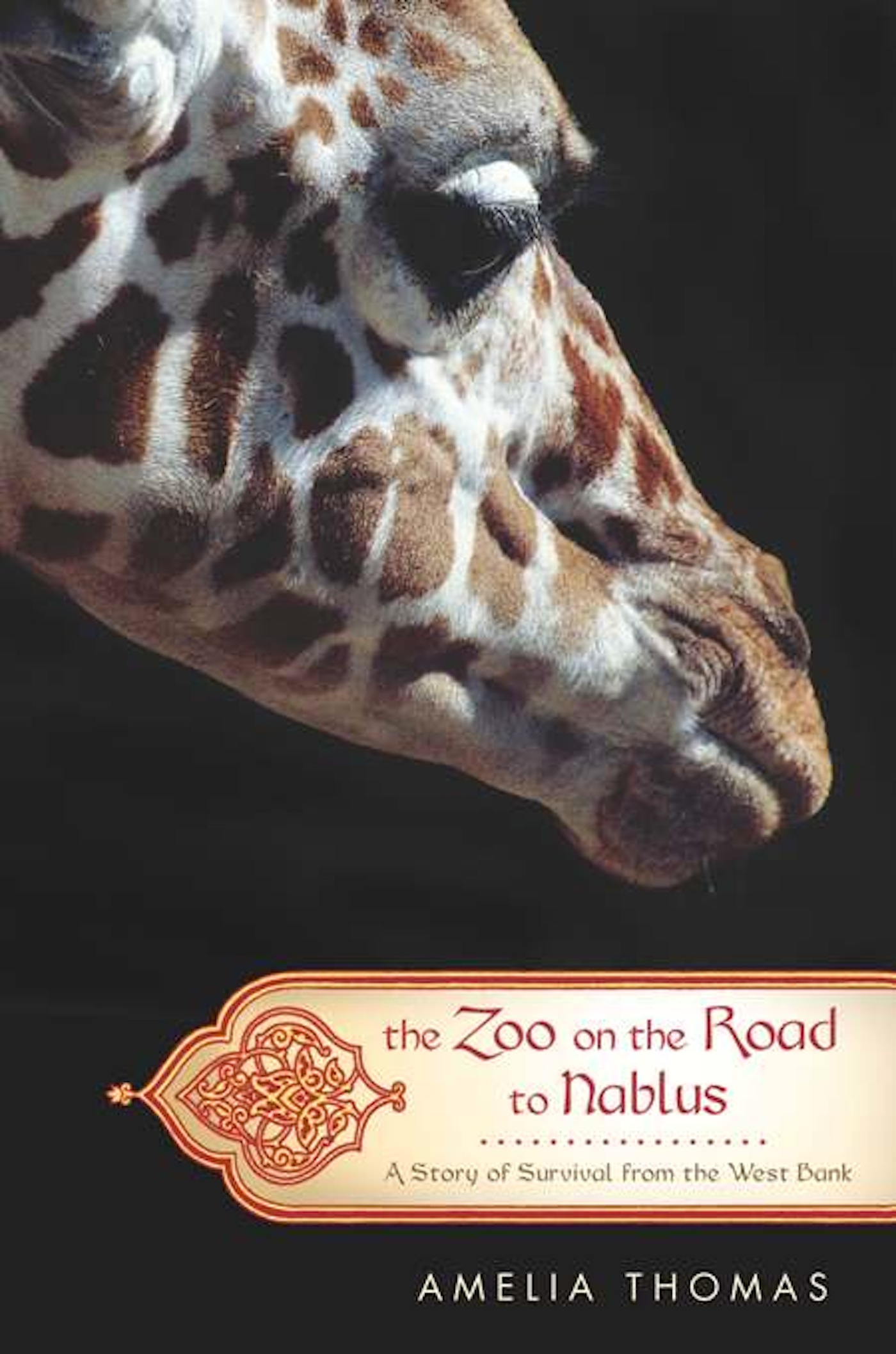

The Zoo on the Road to Nablus

A Story of Survival from the West Bank

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 11, 2008

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586486587

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $16.99 $21.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 11, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The zoo’s bars are rusting; peacocks wander quiet avenues shaded by broad plane trees; a teenage baboon broods in solitary confinement; walls bear the pockmarks of gunfire. And yet the zoo is an extraordinary place, with a bizarre, troubling and inspiring story to tell. At the center of this story is Dr. Sami Khader, the only zoo veterinarian in the Palestinian territories. Family man, amateur inventor, and dedicated taxidermist, he is fiercely independent, apolitical, and resourceful in times of crisis. Dr. Sami dreams of transforming the zoo into one of an international caliber.

In The Zoo on the Road to Nablus, Amelia Thomas brings the reader into a world rarely glimpsed from the outside, weaving the stories of the zoo’s animals, its staff, and its visitors into a rich, colorful chronicle of the indomitability of the human — and animal — spirit.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use