Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

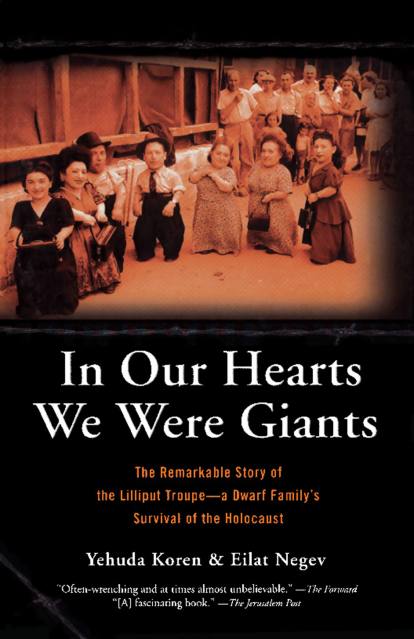

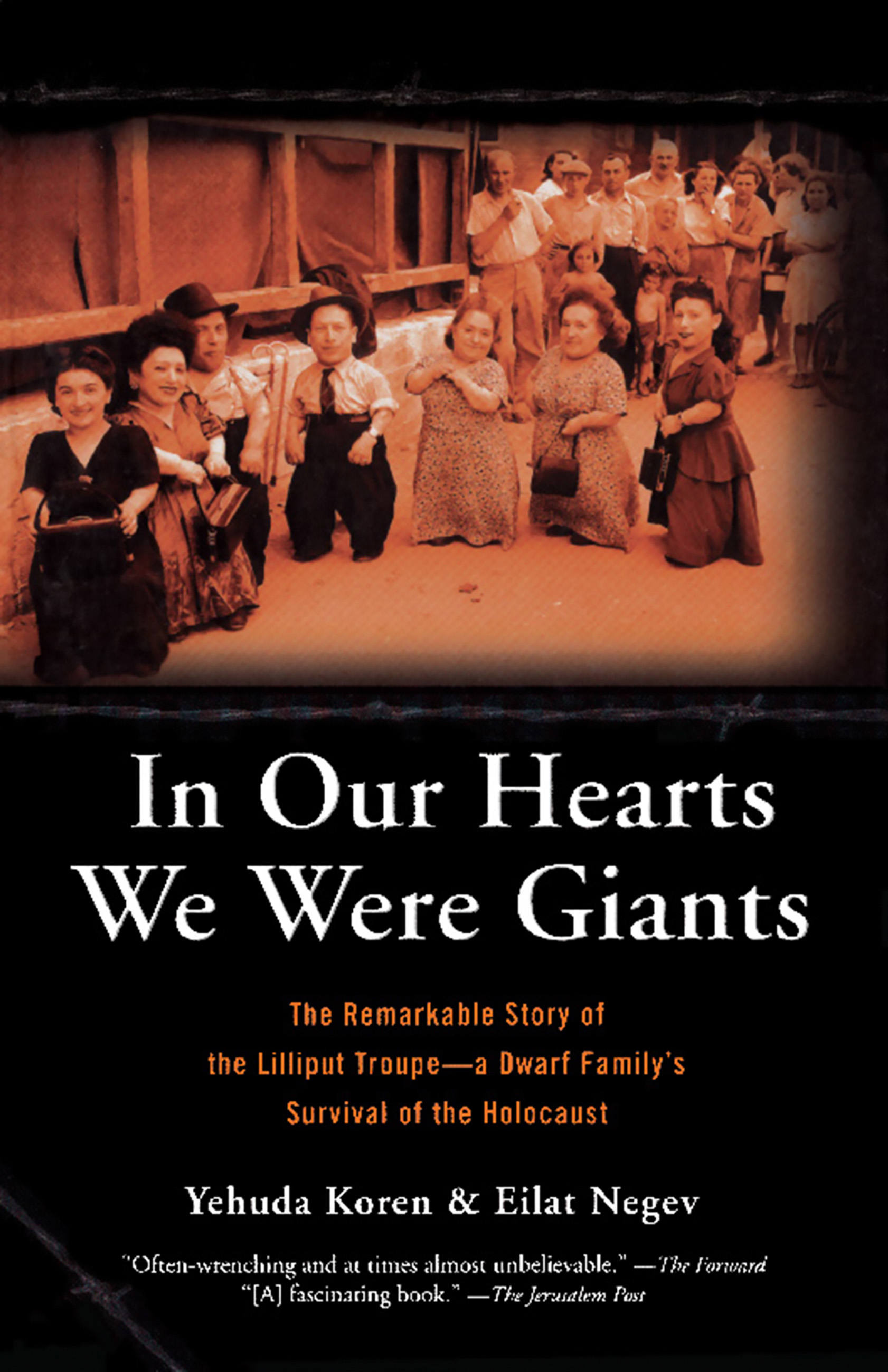

In Our Hearts We Were Giants

The Remarkable Story of the Lilliput Troupe--A Dwarf Family's Survival of the Holocaust

Contributors

By Yehuda Koren

By Eilat Negev

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 27, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In this remarkable, never-before-told account of the Ovitz family, seven of whose ten members were dwarves, readers bear witness to the best and worst of humanity and to the terrible irony of the Ovitz's fate: being burdened with dwarfism helped them endure the Holocaust. Israeli authors Yehuda Koren and Eilat Negev weave the tale of a beloved and successful family of performers who were famous entertainers in Central Europe until the Nazis deported them to Auschwitz in May 1944. Descending into the hell of the concentration camp from the transport train, the Ovitz family—known widely as the Lilliput Troupe—was separated from other Jewish victims. Dr. Josef Mengele was notified of their arrival and they were assigned better quarters and provided more nutritious food than other inmates. The authors chronicle Mengele's experiments upon the Ovitz's, and the creepy fondness he developed for these small people, even the songs he composed and sang to this family of singers, dancers, and klezmorim. Finally liberated by Russian troops, the family returned to their deserted village in Transylvania, and eventually found their way to a new home in Israel. They resumed their careers, overcame their handicaps and became wealthy and successful performers.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 27, 2009

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786738564

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use