Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

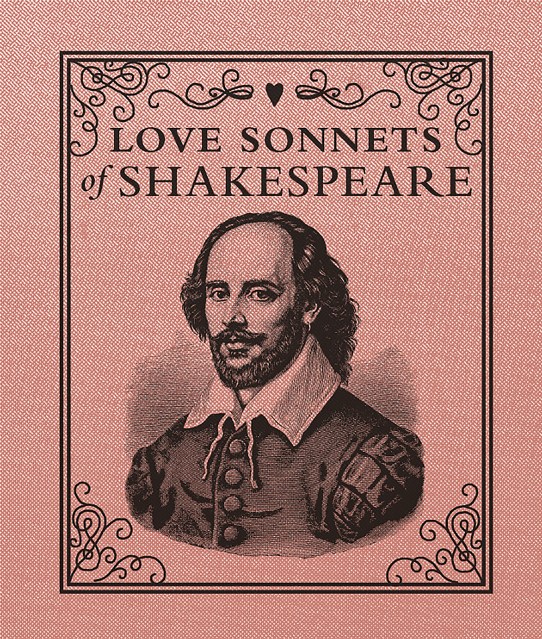

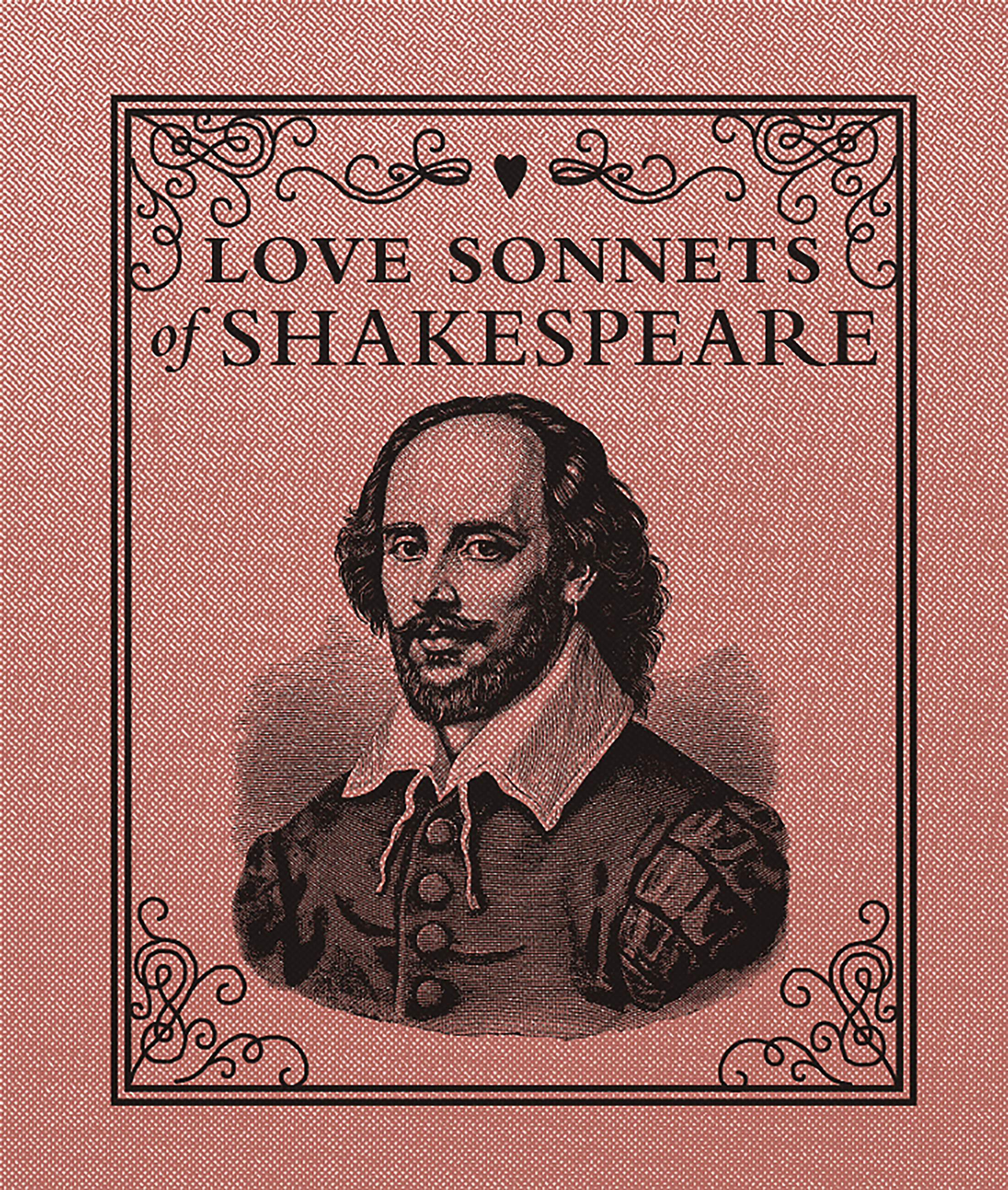

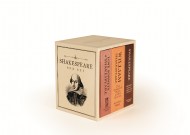

Love Sonnets of Shakespeare

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$7.95Price

$10.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $7.95 $10.50 CAD

- ebook $5.99 $7.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 29, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 29, 2014

- Page Count

- 176 pages

- Publisher

- RP Minis

- ISBN-13

- 9780762454587

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use