Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

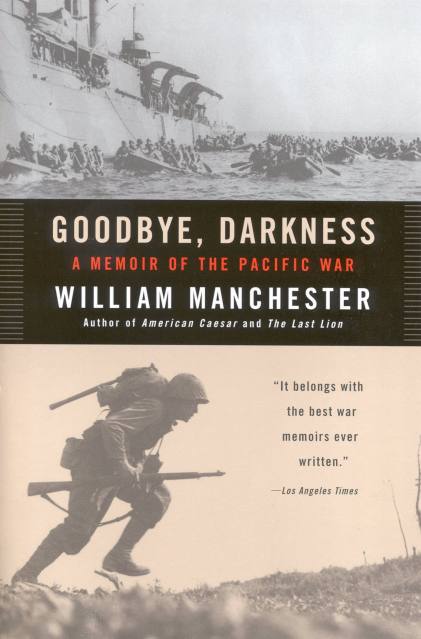

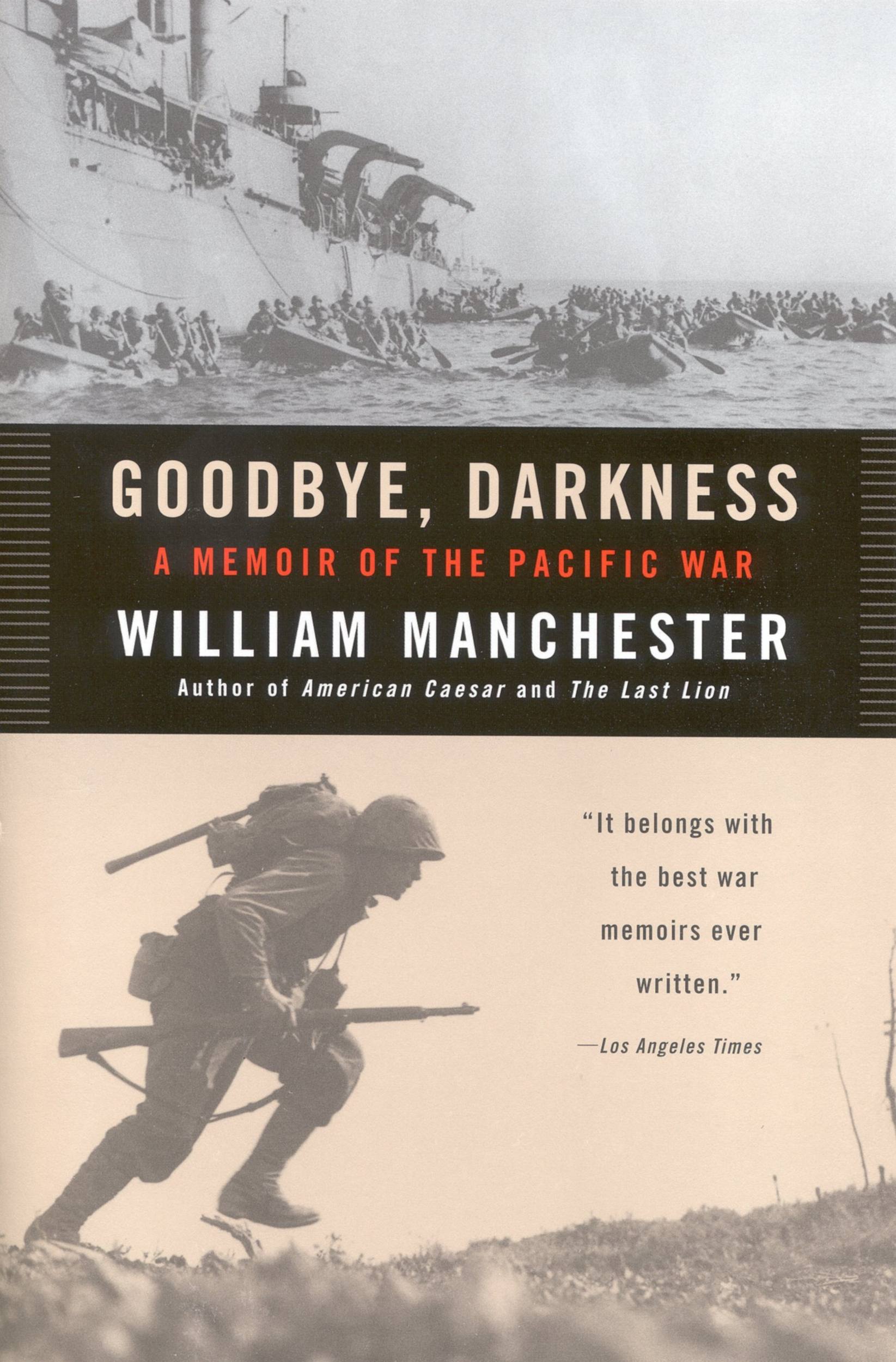

Goodbye, Darkness

A Memoir of the Pacific War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 14, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This emotional and honest novel recounts a young man’s experiences during World War II and digs deep into what he and his fellow soldiers lived through during those dark times.

The nightmares began for William Manchester 23 years after WW II. In his dreams he lived with the recurring image of a battle-weary youth (himself), “angrily demanding to know what had happened to the three decades since he had laid down his arms.” To find out, Manchester visited those places in the Pacific where as a young Marine he fought the Japanese, and in this book examines his experiences in the line with his fellow soldiers (his “brothers”). He gives us an honest and unabashedly emotional account of his part in the war in the Pacific. “The most moving memoir of combat on WW II that I have ever read. A testimony to the fortitude of man…a gripping, haunting, book.” –William L. Shirer

Genre:

- On Sale

- Dec 14, 2008

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316054638

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use