Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

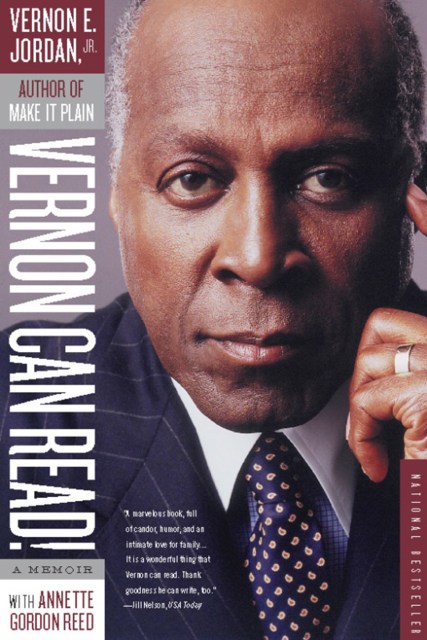

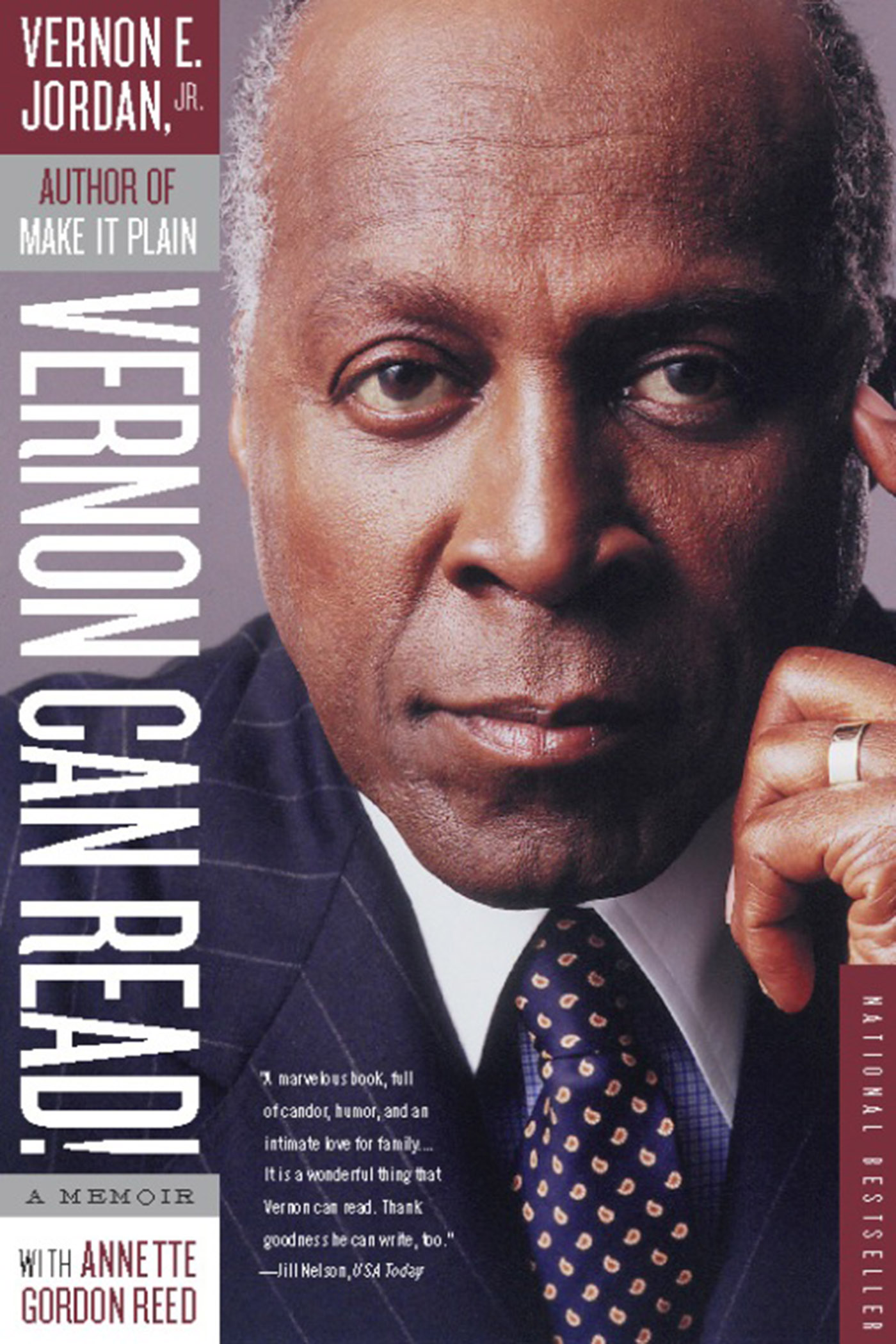

Vernon Can Read!

A Memoir

Contributors

With Annette Gordon-Reed

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 17, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

As a young college student in Atlanta, Vernon E. Jordan, Jr. had a summer job driving a white banker around town. During the man’s post-luncheon siestas, Jordan passed the time reading books, a fact that astounded his boss. “Vernon can read!” the man exclaimed to his relatives. Nearly fifty years later, Vernon Jordan, now a senior executive at Lazard Freres, long-time civil rights leader, adviser and close friend to presidents and business leaders and one of the most charismatic figures in America, has written an unforgettable book about his life and times.

The story of Vernon Jordan’s life encompasses the sweeping struggles, changes, and dangers of African-American life in the civil rights revolution of the second half of the twentieth century.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jun 17, 2009

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786749492

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use