Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

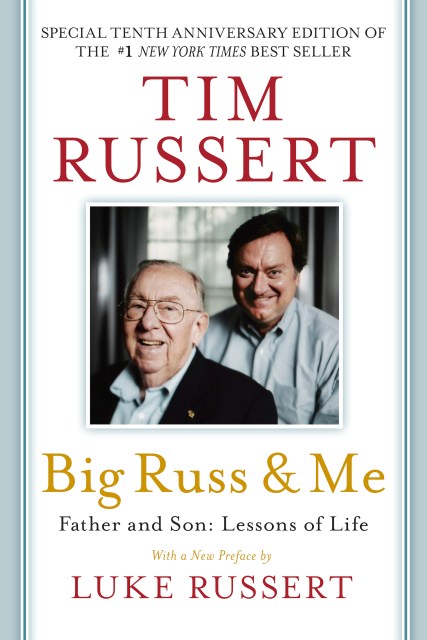

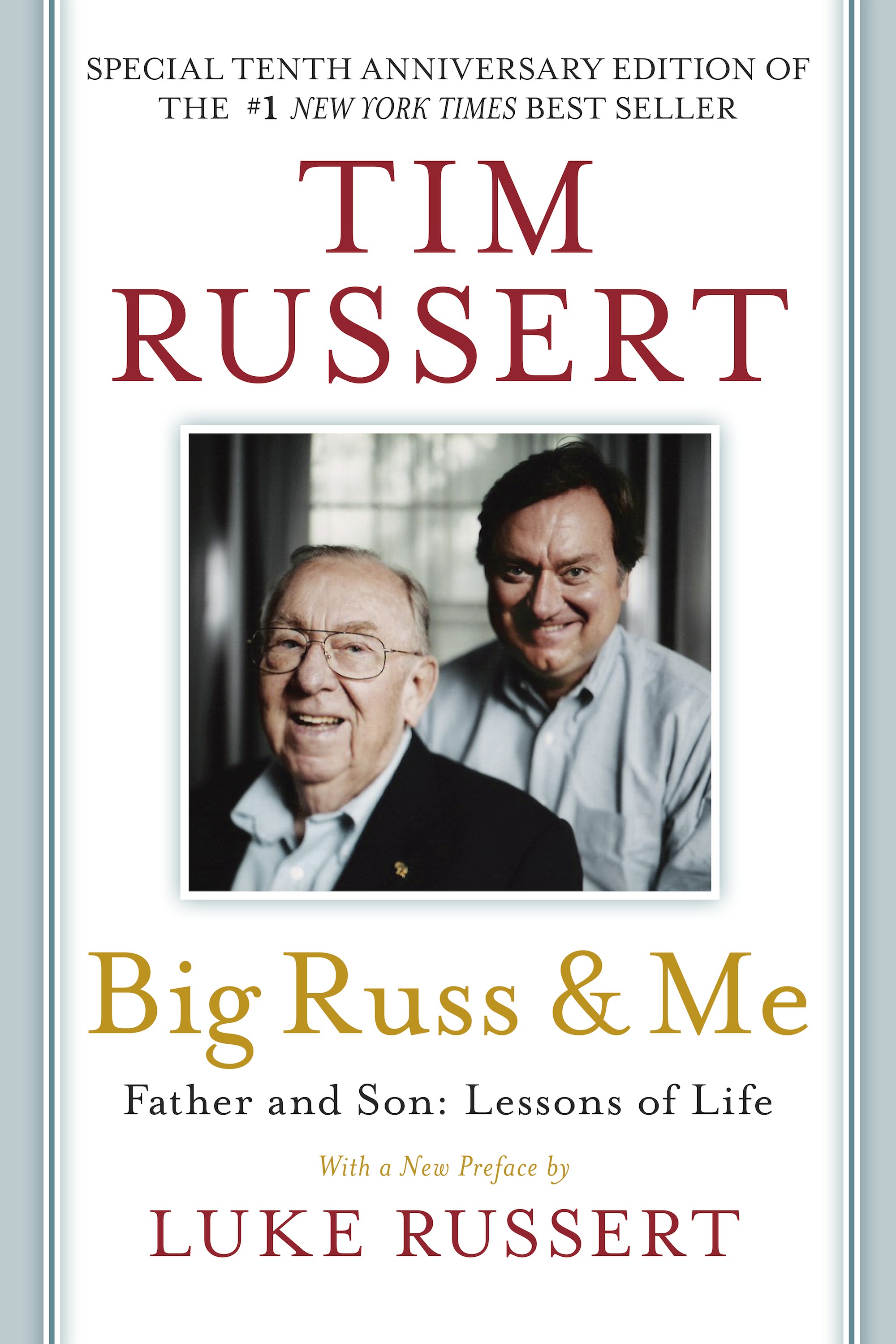

Big Russ & Me

Father & Son: Lessons of Life

Contributors

By Tim Russert

Introduction by Luke Russert

Formats and Prices

Price

$1.99Price

$2.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $1.99 $2.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 6, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

As Tim Russert celebrates the indelible connection between fathers and sons, readers everywhere will laugh and cry in identification with the life lessons of Big Russ and in mourning of Tim Russert, a big American voice in his own right.

Before his death in 2008 at the age of 58, Tim Russert had become one of the most trusted and admired figures in American television journalism. Throughout his career he spent time with presidents and popes, world leaders and newsmakers, celebrities and sports heroes, but one person stood out to him in terms of his strength of character, modest grace and simple decency—Russert's dad, Big Russ.

In this warm, engaging memoir, a #1 New York Times bestseller, Russert casts a fond look back to the 1950s Buffalo neighborhood of his youth. In the close-knit Irish-Catholic community where grew up, doors were left unlocked at night; backyard ponds became makeshift ice hockey rinks in winter; and streets were commandeered as touch football fields in the fall. And he recalls the extraordinary example of his father, a WWII veteran who worked two jobs without complaint for thirty years and taught his children to appreciate the values of self-discipline, of respect, of loyalty to friends.

These deep roots stayed with Russert as he forged a remarkable career, first in government and then in media, and finally in his 16 years at Meet the Press as one of the most recognized and trusted face in television news. As Russert explains, his fundamental values sprung from that small house on Woodside Avenue and the special bond he shared with his father—values he passed down to his own son, Luke.

For this special 10th anniversary edition, Luke contributes an extensive introduction, commenting on his father's legacy, and on how these lessons passed down from his grandfather impact the third generation. Luke had just graduated from college in 2008 when his father passed away. He worked as a special correspondent and congressional reporter for NBC news and contributed frequently to various NBC and MSNBC outlets before leaving on a three-year odyssey to grieve his father's death. Luke has already shown that the ideals promoted by Big Russ in midcentury Buffalo still apply in 21st century New York, and that these lessons are as relevant for us as ever.

Before his death in 2008 at the age of 58, Tim Russert had become one of the most trusted and admired figures in American television journalism. Throughout his career he spent time with presidents and popes, world leaders and newsmakers, celebrities and sports heroes, but one person stood out to him in terms of his strength of character, modest grace and simple decency—Russert's dad, Big Russ.

In this warm, engaging memoir, a #1 New York Times bestseller, Russert casts a fond look back to the 1950s Buffalo neighborhood of his youth. In the close-knit Irish-Catholic community where grew up, doors were left unlocked at night; backyard ponds became makeshift ice hockey rinks in winter; and streets were commandeered as touch football fields in the fall. And he recalls the extraordinary example of his father, a WWII veteran who worked two jobs without complaint for thirty years and taught his children to appreciate the values of self-discipline, of respect, of loyalty to friends.

These deep roots stayed with Russert as he forged a remarkable career, first in government and then in media, and finally in his 16 years at Meet the Press as one of the most recognized and trusted face in television news. As Russert explains, his fundamental values sprung from that small house on Woodside Avenue and the special bond he shared with his father—values he passed down to his own son, Luke.

For this special 10th anniversary edition, Luke contributes an extensive introduction, commenting on his father's legacy, and on how these lessons passed down from his grandfather impact the third generation. Luke had just graduated from college in 2008 when his father passed away. He worked as a special correspondent and congressional reporter for NBC news and contributed frequently to various NBC and MSNBC outlets before leaving on a three-year odyssey to grieve his father's death. Luke has already shown that the ideals promoted by Big Russ in midcentury Buffalo still apply in 21st century New York, and that these lessons are as relevant for us as ever.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 6, 2014

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781602862630

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use