Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

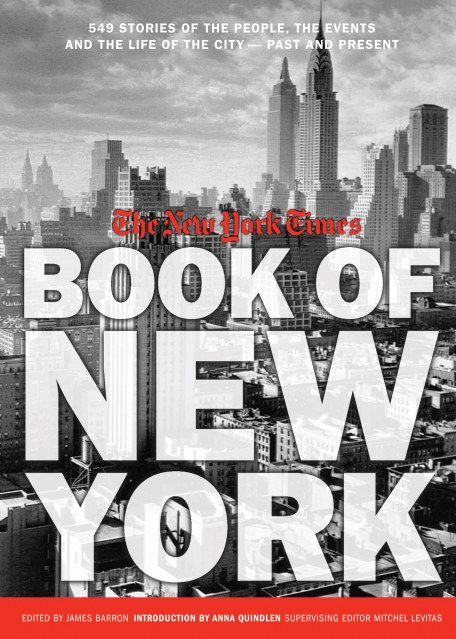

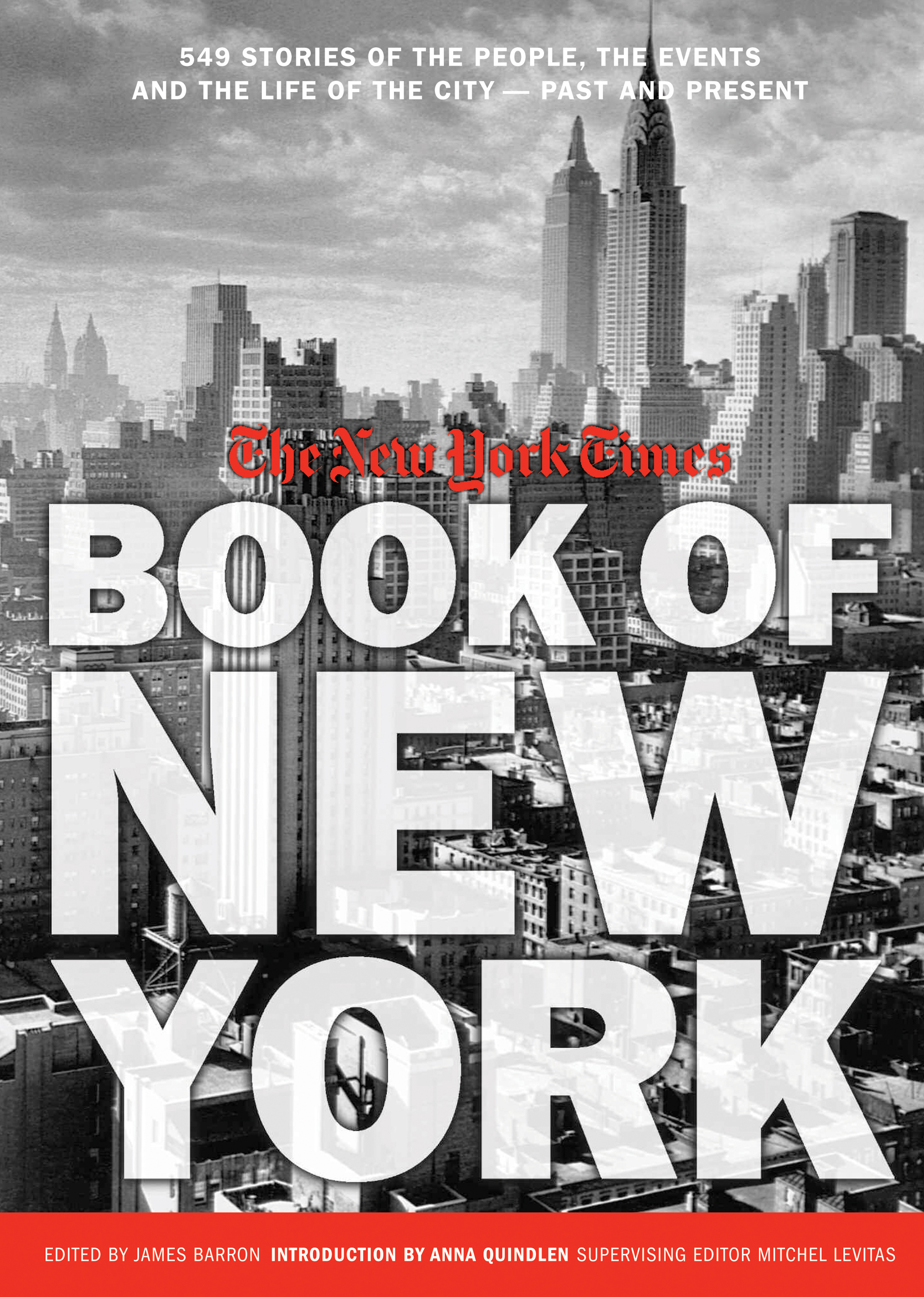

New York Times Book of New York

Stories of the People, the Streets, and the Life of the City Past and Present

Contributors

Edited by James Barron

Editorial coordination by Mitchel Levitas

Introduction by Anna Quindlen

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $14.99 $19.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 20, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

More than 200 articles and an abundance of photographs, illustrations, maps, and graphs from the preeminent newspaper in the world take a look at the history and personality of the world’s most influential city. Read firsthand accounts of the subway opening in 1904 and the day the Metrocard was introduced; the fall of Tammany Hall and recurring corruption in city politics; the Son of Sam murders; jazz clubs in the 1920s and legendary performances at the Fillmore East; baseball’s Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier at Brooklyn’s storied Ebbets Field in 1947; the 1977 and 2004 blackouts; the openings and closings of the city’s most beloved restaurants; and much more. Not just a historical account, this is a fascinating, sometimes funny, and often moving look at how people in New York live, eat, travel, mourn, fight, love, and celebrate.

Organized by theme, the book includes original writings on all topics related to city life, including art, architecture, transportation, politics, neighborhoods, people, sports, business, food, and more. Includes articles from such well-known Times writers as Meyer Berger, Gay Talese, Anna Quindlen, Israel Shenker, Brooks Atkinson, Frank Rich, Ada Louise Huxtable, John Kieran, Russell Baker, and more. Special contributors who have written about New York for the Times include Paul Auster, Woody Allen, and E.B. White, among others.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 20, 2009

- Page Count

- 463 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9781603763691

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use