Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

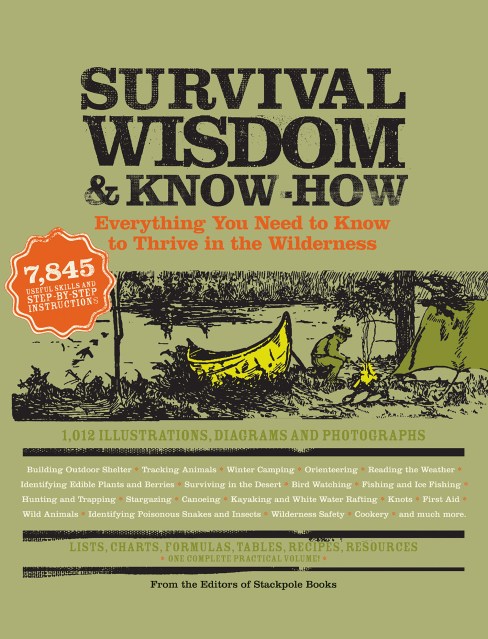

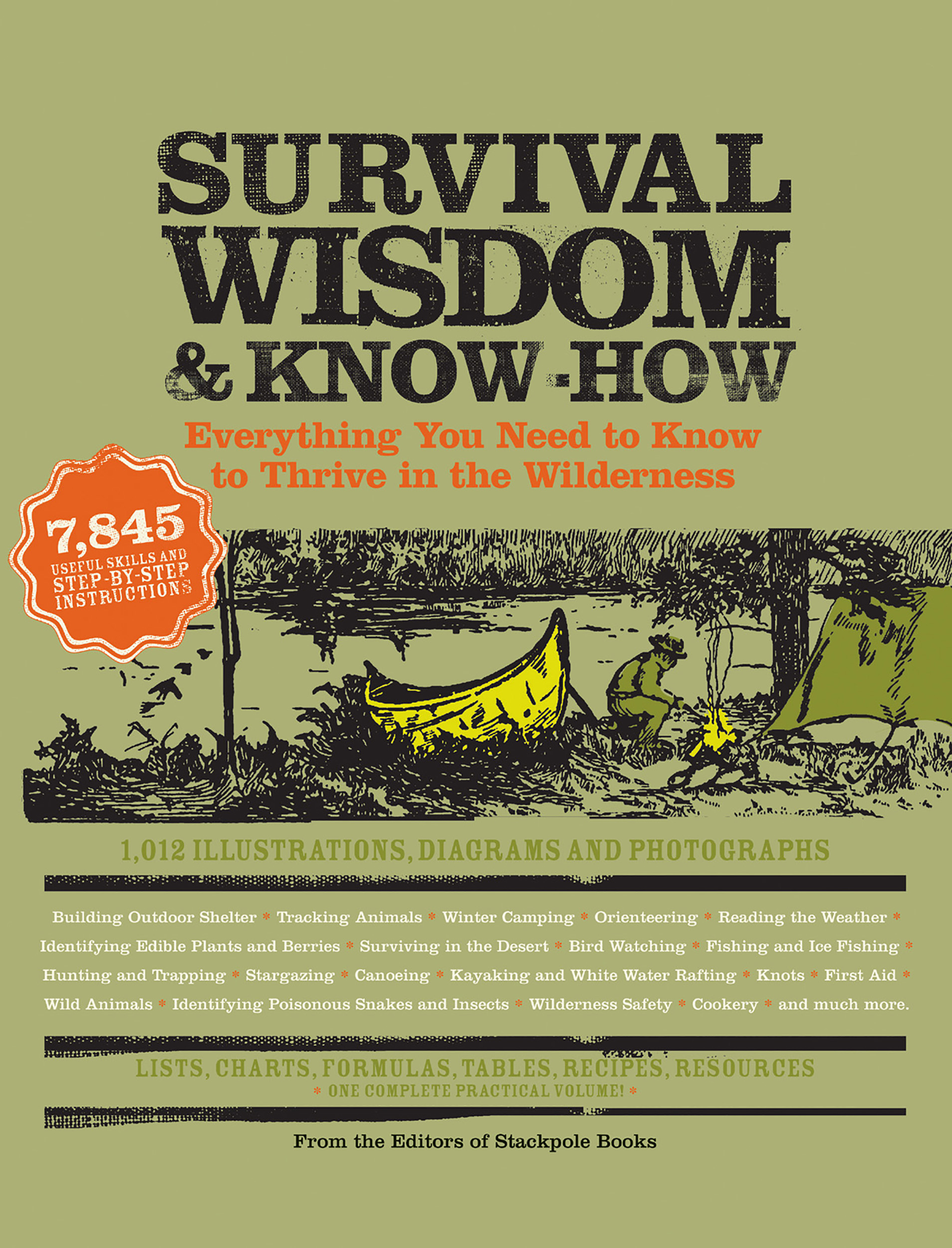

Survival Wisdom & Know How

Everything You Need to Know to Thrive in the Wilderness

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $30.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 19, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Culled from dozens of respected books from Stackpole — the industry’s leader in outdoor adventure — this massive collection of wilderness know-how leaves absolutely nothing to chance when it comes to surviving and thriving outdoors. Topics include:

- Orienteering

- Building an Outdoor Shelter

- Hunting and Tracking Animals

- Tying Knots

- Identifying Edible Plants and Berries

- Surviving in the Desert

- Fishing and Ice Fishing

- Canoeing, Kayaking, and White Water Rafting

- And so much more!

Useful illustrations and photos throughout make it easy to browse and use. With contributions by the experts at the National Outdoor Leadership School as well as the editors of Stackpole’s Discover Nature series, this book is the definitive, must-have reference for the great outdoors.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 19, 2012

- Page Count

- 488 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9781603762731

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use