Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

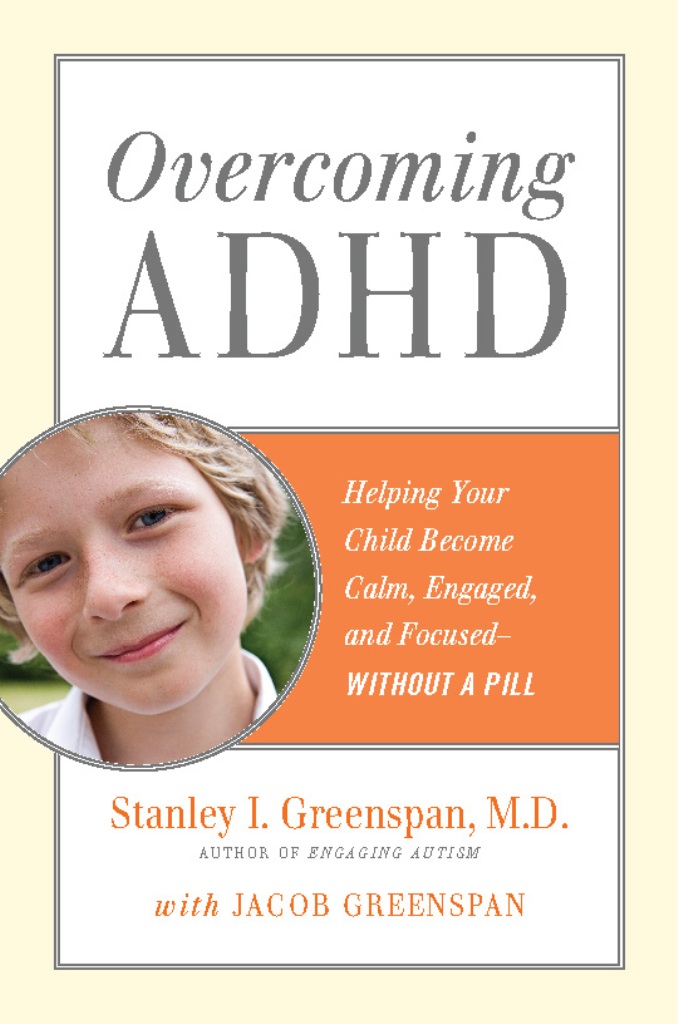

Overcoming ADHD

Helping Your Child Become Calm, Engaged, and Focused -- Without a Pill

Contributors

With Jacob Greenspan

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $13.99 $17.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 11, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This wise and informative guide applies Stanley Greenspan’s much admired developmental approach to a very common disorder. In his distinctive and original view, ADHD is not a single problem, but rather a set of common symptoms that arise from several different sensory, motor, and self-regulation problems. As in his highly successful earlier books and in his practice, Greenspan emphasizes the role of emotion, seeking the root of the condition and rebuilding the foundations of healthy development. Overcoming ADHD steers away from the pitfalls of labeling, or of simply stamping out symptoms with medication, and demonstrates Greenspan’s abiding belief in the growth and individual potential of each child.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 11, 2009

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Lifelong Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780786745968

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use