Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

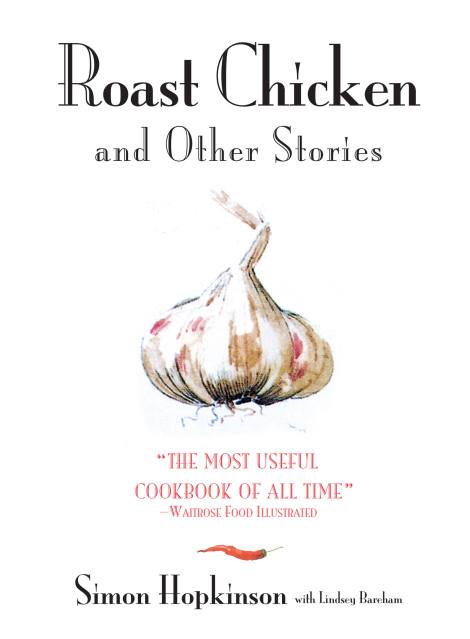

Roast Chicken and Other Stories

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $13.99 $17.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 23, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In England, no food writer’s star shines brighter than Simon Hopkinson’s. His breakthrough Roast Chicken and Other Stories was voted the most useful cookbook ever by a panel of chefs, food writers, and consumers. At last, American cooks can enjoy endearing stories from the highly acclaimed food writer and his simple yet elegant recipes.

In this richly satisfying culinary narrative, Hopkinson shares his unique philosophy on the limitless possibilities of cooking. With its friendly tone backed by the author’s impeccable expertise, this cookbook can help anyone–from the novice cook to the experienced chef–prepare delicious cuisine . . . and enjoy every minute of it!

Irresistible recipes in this book include:

Eggs Florentine

Chocolate Tart

Poached Salmon with Beurre Blanc

And, of course, the book’s namesake recipe, Roast Chicken

Winner of both the 1994 Andre Simon and 1995 Glenfiddich awards (the gastronomic world’s equivalent to an Oscar), this acclaimed book will inspire anyone who enjoys sharing the ideas of a truly creative cook and delights in getting the best out of good ingredients.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 23, 2013

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781401306144

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use