Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

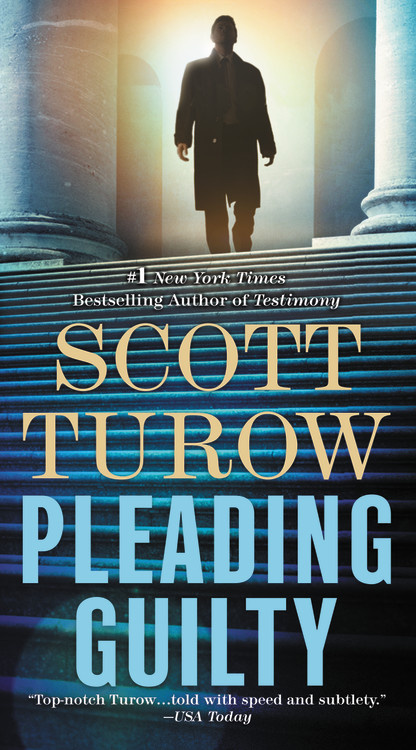

Pleading Guilty

Contributors

By Scott Turow

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 30, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Genre:

-

"Mr. Turow's prose is powerful ... a tough, vivid urban poetry, singing of ambition and corruption.... an arresting performance."New York Times

-

"Though every element of the novel is polished and professional, the charisma of Mack's narration is its triumph. Add that to a taut, twist-filled plot, expert pacing, colorful and well-rendered supporting characters, and an appealing whiff of larceny, and Turow surpasses Grisham hands down."Publishers Weekly

-

"His legions of fans surely won't miss the chance to see Turow as they've never seen him before."Kirkus Reviews

- On Sale

- May 30, 2017

- Page Count

- 496 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538727140

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use