Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

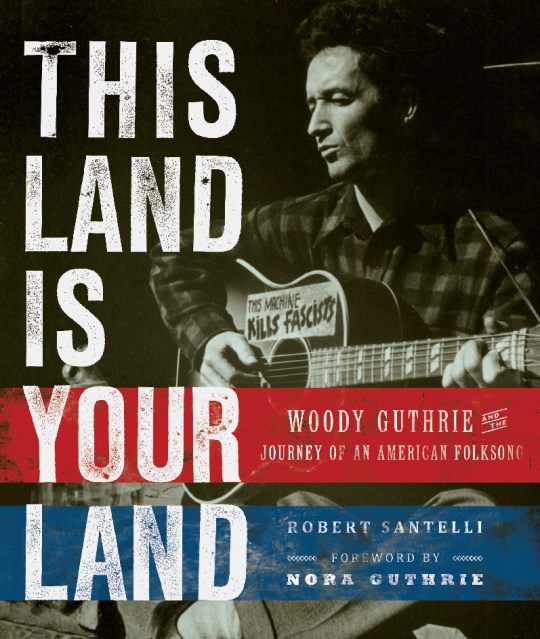

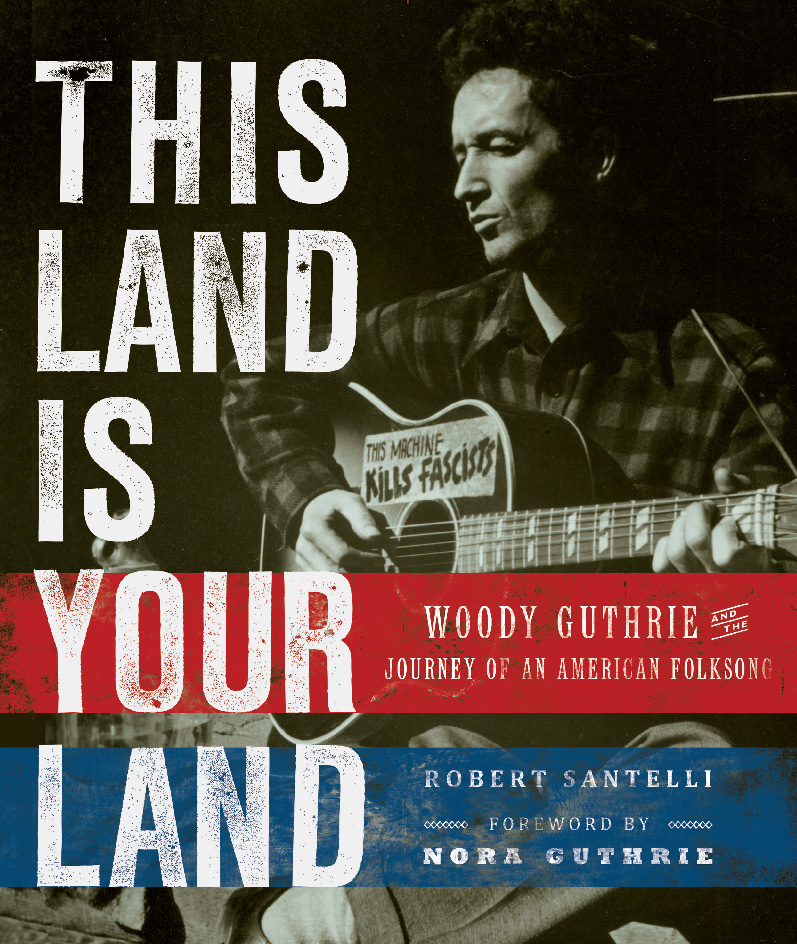

This Land Is Your Land

Woody Guthrie and the Journey of an American Folk Song

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $14.99 $19.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 13, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The book will publish to coincide with "Woody at 100" — a partnership between the Grammy Museum and the Guthrie Archives to stage numerous celebratory events throughout 2012 nationwide and beyond.

This Land Is Your Land is a remarkably detailed account of the journey of America's most celebrated folk song. It also details Guthrie's legendary journey from Oklahoma across the Heartland to New York City, where he wrote many of his works including "This Land Is Your Land."

With more than forty rare black-and-white photographs from the Woody Guthrie archives plus original interviews with Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Willie Nelson, Pete Seeger, John Mellencamp, and more, This Land Is Your Land delivers a revealing portrait of an American treasure.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 13, 2012

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762445080

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use