Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

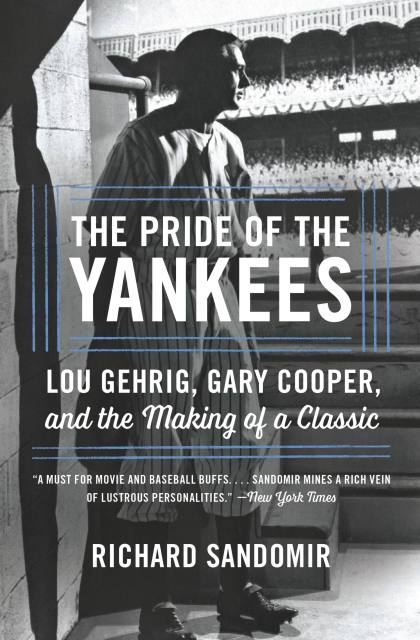

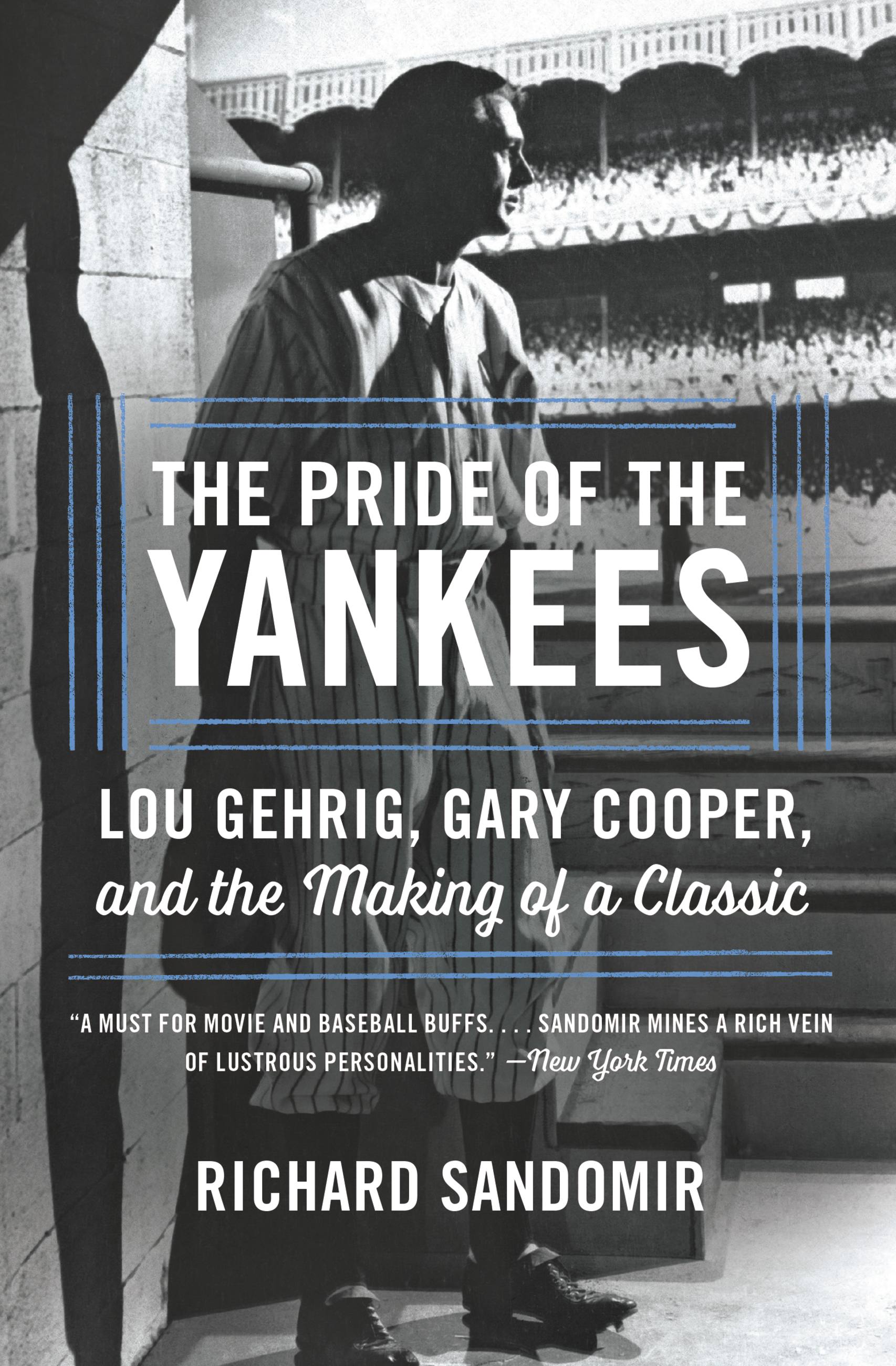

The Pride of the Yankees

Lou Gehrig, Gary Cooper, and the Making of a Classic

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 13, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

On July 4, 1939, baseball great Lou Gehrig delivered what has been called “baseball’s Gettysburg Address” at Yankee Stadium and gave a speech that included the phrase that would become legendary. He died two years later and his fiery widow, Eleanor, wanted nothing more than to keep his memory alive. With her forceful will, she and the irascible producer Samuel Goldwyn quickly agreed to make a film based on Gehrig’s life, The Pride of the Yankees. Goldwyn didn’t understand — or care about — baseball. For him this film was the emotional story of a quiet, modest hero who married a spirited woman who was the love of his life, and, after a storied career, gave a short speech that transformed his legacy. With the world at war and soldiers dying on foreign soil, it was the kind of movie America needed.

Using original scrips, letters, memos, and other rare documents, Richard Sandomir tells the behind-the-scenes story of how a classic was born. There was the so-called Scarlett O’Hara-like search to find the actor to play Gehrig; the stunning revelations Elanor made to the scriptwriter Paul Gallico about her life with Lou; the intensive training Cooper underwent to learn how to catch, throw, and hit a baseball for the first time; and the story of two now-legendary Hollywood actors in Gary Cooper and Teresa Wright whose nuanced performances endowed the Gehrigs with upstanding dignity and cemented the baseball icon’s legend.

Sandomir writes with great insight and aplomb, painting a fascinating portrait of a bygone Hollywood era, a mourning widow with a dream, and the shadow a legend cast on one of the greatest sports films of all time.

Genre:

-

"Intriguing...a must for movie and baseball buffs...Sandomir mines a rich vein of lustrous personalities."The New York Times

-

"The riveting story behind the making of The Pride of the Yankees is finally being told in Richard Sandomir's meticulously researched and gracefully written book. He brings to vivid life Eleanor Gehrig, Gary Cooper, and Samuel Goldwyn's efforts to turn a hero's life into a heartfelt film."Gay Talese

-

"It wouldn't be much of a stretch to call Sandomir's book as much of a classic as the movie that inspired it."Minneapolis Star-Tribune

-

"If you grew up with The Pride of the Yankees as a yearly staple on Ch. 11--or just watch it now whenever it pops up on MLB Network--you must read Richard Sandomir's book of the same name on the making of that wonderful movie....You'll be done - and ready to watch the movie all over again"Mike Vaccaro, New York Post

-

"The brave, tragic story of Lou Gehrig, the great baseball player, was a script waiting to be written. With affection and reportorial savvy, Richard Sandomir describes how one myth begat another to produce the legendary baseball movie that still can make people cry. The Pride of the Yankees recalls a lost world, when Hollywood had the power to create dreams that people wanted to believe."Julie Salamon, author of The Devil's Candy and Wendy and the Lost Boys

-

"More than the story of a movie or even an era of baseball, Richard Sandomir's brilliantly reported book transports us back to an age of real heroes who had both grit and elegance. In doing so, he issues a valuable challenge to today's stars: character matters."James Andrew Miller, bestselling author of Those Guys Have All the Fun: Inside the World of ESPN

-

"How was Lou Gehrig's timeless story brought to the Big Screen? Richard Sandomir answers that question with deft precision and warmth."Tim McCarver, former MLB catcher and announcer for the St. Louis Cardinals

-

"Sandomir spotlights a significant moment in baseball history and solidifies Gehrig for a new generation of Yankees fans."ESPN.com

-

"The fascinating inside story of the 75-year-old film....Even if you've seen the movie 100 times, this book will give you a different perspective."The Chicago Tribune

-

"There are very few great movies about sports, but after more than seventy years The Pride of the Yankees remains at the top of the roster because it focuses on the pride and grace that sports, at their best, display. As Richard Sandomir's fascinating book shows, this beautiful movie emerged simply because Samuel Goldwyn needed a vehicle for Gary Cooper, whose gift for quiet anguish made Lou Gehrig immortal. It's an irresistible story."Scott Eyman, New York Times bestselling author of John Wayne: Life and Legend

-

"Packed with fascinating new detail, The Pride of the Yankees will be the delight of baseball fans and movie buffs. Think of it as a triple play: great ballplayer, great movie, great book."Jonathan Eig, author of Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig

-

"An authoritative take on what's factual (not that much), what's fanciful (a whole lot) and what's a bit of both....fans of film and baseball will appreciate Sandomir's book."The Associated Press

-

"When it comes to the confluence of sports, business and culture, nobody hits and fields like Rich Sandomir, an all-star, maybe even an Iron Horse."Robert Lipsyte, author of An Accidental Sportswriter

-

"Sandomir has written a great book about a movie and a man who has inspired millions. Timed to the 75th anniversary of the film's release, it would make an excellent Father's Day gift."Sporting News

-

"Think you know all there is to know about Lou Gehrig and the movie that so movingly tells his tragic story? Think again. In this fascinating new book, the great Richard Sandomir takes us inside the making of The Pride of the Yankees while also delivering rich new detail about Gehrig's short life. It's a cliche to say this book is a home run, but it's true. It is."Christine Brennan, USA Today sports columnist and ABC News, CNN, and NPR commentator

-

"New York Times sports columnist Richard Sandomir reveals for the first time the full story behind the pioneering, seminal movie. Filled with larger than life characters and unexpected facts, the book shows us how Samuel Goldwyn had no desire to make a baseball film but he was persuaded to make a quick deal with Lou's widow, Eleanor, not long after Gehrig had passed. A great book if you want to know, in the immortal words of the late Paul Harvey, 'the rest of the story.'"Forbes.com

-

"Richard Sandomir was as well cast to write this book as Gary Cooper was to play the great Gehrig. Baseball fans and movie lovers will devour this book."David Maraniss, author of When Pride Still Mattered and Clemente

-

"In this emotional and fascinating tale, Sandomir brilliantly captures the spirit of the film and Gehrig's life. Film lovers and baseball fans will enjoy."Library Journal

-

"An affectionate look at the making of the 1942 baseball biopic Pride of the Yankees, the rarest of movies--an American icon played by an American icon."Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

-

"This book is so enjoyable that one day there will be a book about the making of the book that told the story of the making of the movie."Marty Appel, former public relations director for the New York Yankees and author of Pinstripe Empire: The New York Yankees from Before the Babe to After the Boss

- On Sale

- Jun 13, 2017

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316355162

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use