Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

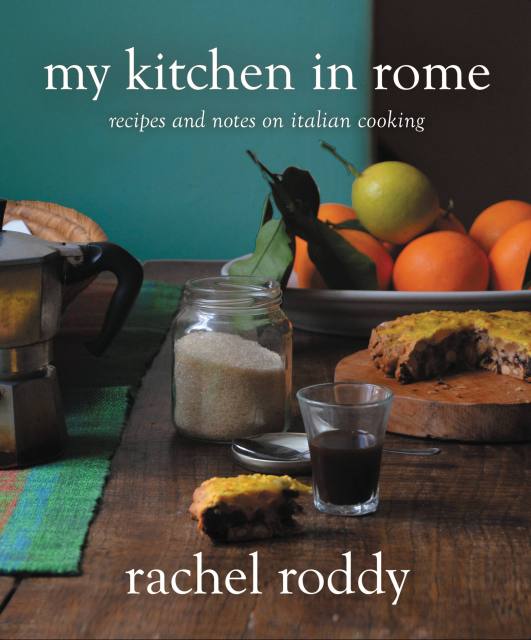

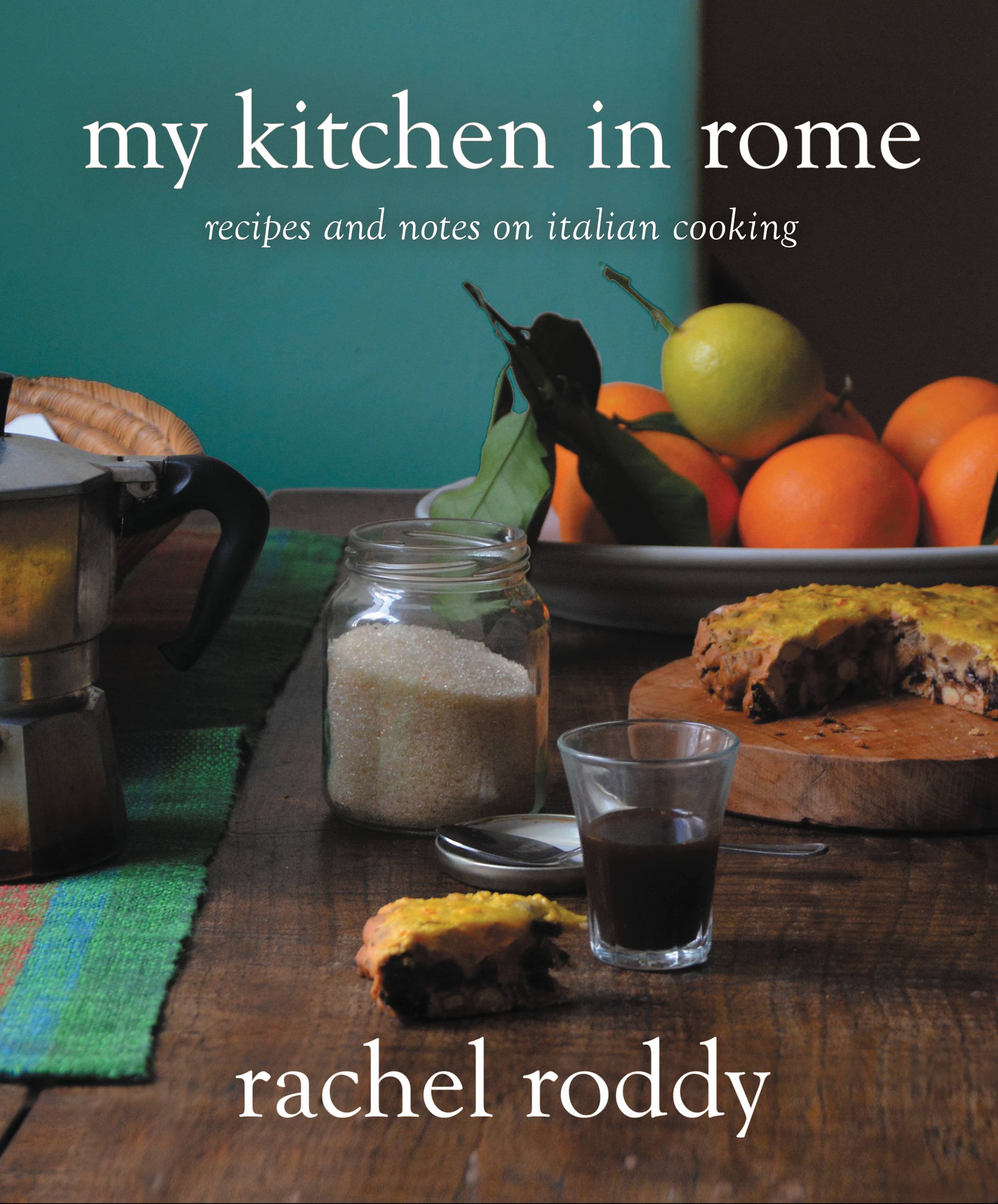

My Kitchen in Rome

Recipes and Notes on Italian Cooking

Contributors

By Rachel Roddy

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $14.99 $19.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 2, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Weaving together stories, memories, and recipes for thick bean soups, fresh pastas, braised vegetables, and slow-cooked meats, My Kitchen in Rome captures the spirit of Rachel’s beloved blog, Rachel Eats, and offers readers the chance to cook “cucina romana” without leaving the comfort of home.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Feb 2, 2016

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Life & Style

- ISBN-13

- 9781455585175

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use