Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

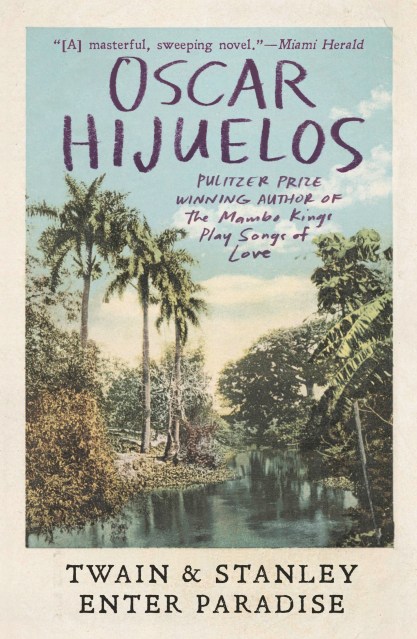

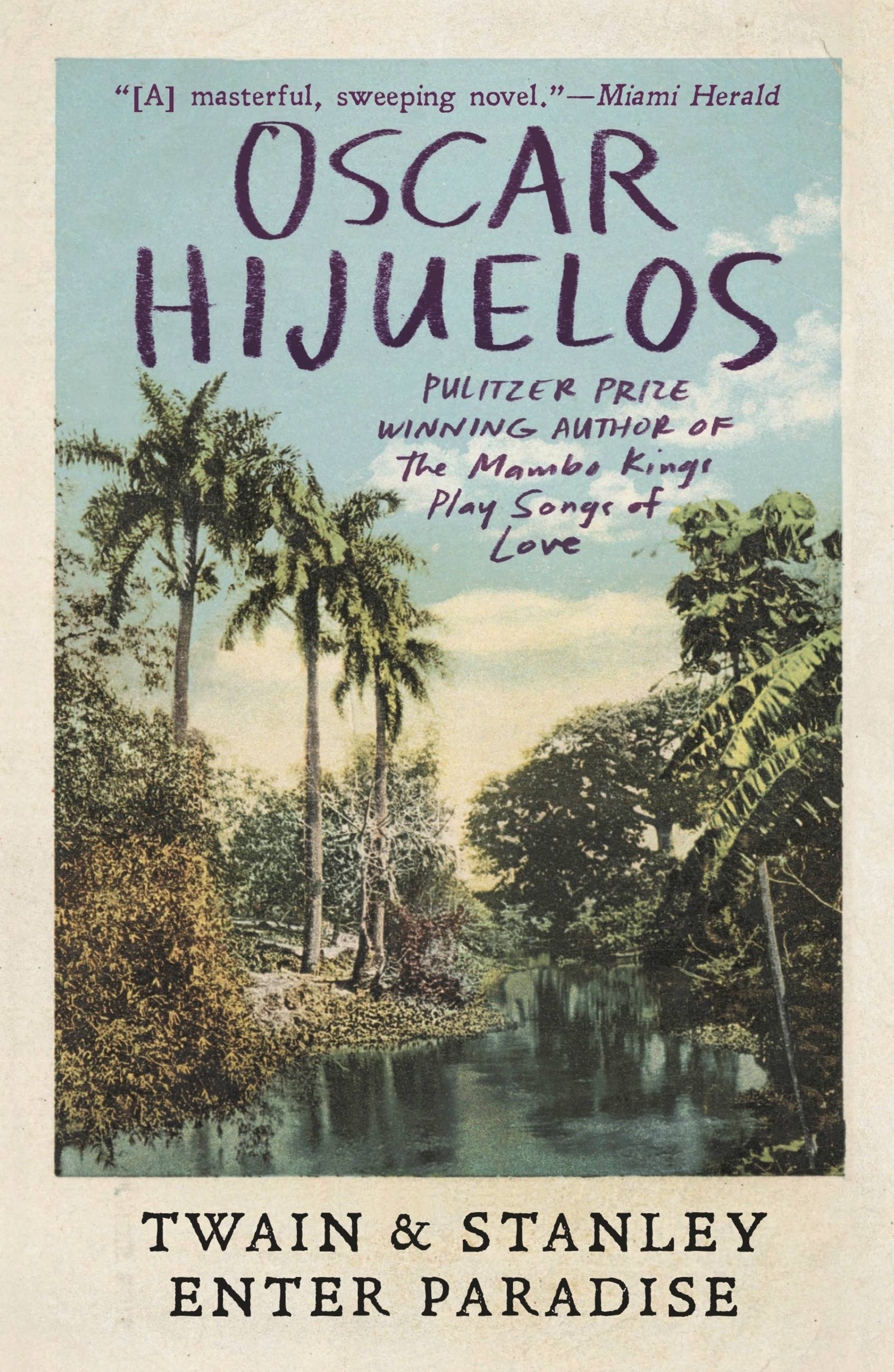

Twain & Stanley Enter Paradise

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 4, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

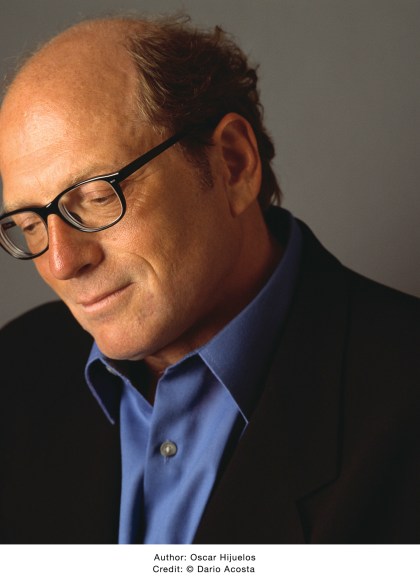

Hijuelos was fascinated by the Twain-Stanley connection and eventually began researching and writing a novel that used the scant historical record of their relationship as a starting point for a more detailed fictional account. It was a labor of love for Hijuelos, who worked on the project for more than ten years, publishing other novels along the way but always returning to Twain and Stanley; indeed, he was still revising the manuscript the day before his sudden passing in 2013.

The resulting novel is a richly woven tapestry of people and events that is unique among the author’s works, both in theme and structure. Hijuelos ingeniously blends correspondence, memoir, and third-person omniscience to explore the intersection of these Victorian giants in a long vanished world.

From their early days as journalists in the American West, to their admiration and support of each other’s writing, their mutual hatred of slavery, their social life together in the dazzling literary circles of the period, and even a mysterious journey to Cuba to search for Stanley’s adoptive father, Twain & Stanley Enter Paradise superbly channels two vibrant but very different figures. It is also a study of Twain’s complex bond with Mrs. Stanley, the bohemian portrait artist Dorothy Tennant, who introduces Twain and his wife to the world of sv©ances and mediums after the tragic death of their daughter.

A compelling and deeply felt historical fantasia that utilizes the full range of Hijuelos’ gifts, Twain & Stanley Enter Paradise stands as an unforgettable coda to a brilliant writing career.

Genre:

-

"Oscar Hijuelos, who left us suddenly and far too soon, has been deeply missed by those of us who were his friends-missed both as a friend and as a writer. The friend will not be coming back, but what a miracle that he has given us this last novel-which is a fine and wonderful novel, and surely among the best books Oscar ever wrote."Paul Auster

-

"The great Oscar Hijuelos lives on in this ambitious, fascinating, and richly detailed work that, like the author, is in a class by itself."Gay Talese

-

"TWAIN & STANLEY ENTER PARADISE is a natural and delightful extension of Hijuelos' work, and like his earlier books, this one is distinguished by vitality so intense as to give the reader a charge just picking up the book. . . . a voice that is haunting and mesmerizing, and a story that shows just how fantastic and enjoyable Oscar Hijuelos' imagination really was."Craig Nova, author of The Good Son

-

"What a wonder to have Oscar Hijuelos return from the celestial beyond with a tale that is thoroughly of this world and firmly anchored in history! TWAIN & STANLEY ENTER PARADISE is a marvelous blend of research and the imagination, resurrecting two fascinating contemporaries-Mark Twain and Henry Morton Stanley-and lending a bygone era the shimmer of here and now."Marie Arana, author of American Chica, Cellophane, and Bolívar: American Liberator.

-

"An extraordinary feat of imaginative historical re-creation."Booklist (starred review)

-

"Vividly imagined and detailed epic...How lucky we are to have this rich novel."Publisher's Weekly (starred review)

-

"The final masterpiece by the Pulitzer-Prize-winning writer....Twain fans, get ready."Huffington Post

-

"A magical story."David Baldacci, CBS Sunday Morning

-

"This book is good news for Hijuelos fans."Kirkus

-

"So sad that this is our last Hijuelos novel, so fabulous that we have it."Library Journal (starred review)

-

"A brilliant posthumous capstone."EW.com

-

"It is a rollicking adventure tale, bromance, and portrait of two fascinating men who battled their way to prominence during an era defined by yellow fever, the Civil War, and a pioneering American zeal."O, The Oprah Magazine

-

Praise for Mr. Ives' Christmas:New York Times Book Review

"The novel is full of suspense...A tale of...goodwill lost and goodwill regained. The deepest and best of Hijuelos's novels." -

"His most powerful book yet....A wonderfully affecting tale."New York Times

-

"Stunning....A triumph....With an hoesty at its core that seems almost shocking in this day and age."Boston Globe

-

"Enthralling....A life-affirming novel, a worthy successor to Dickens."Philadelphia Inquirer

-

Praise for The Mambo Kings:New York Times Book Review

"A rich and sorrowful novel...that alternates crisp narrative with opulent musings--the language of everyday and the language of longing. You finish feeling...ready to throw up your arms and cry, Que bueno es! Mr. Hijuelos is writing music of the heart" -

"By turns street-smart and lyrica, impassioned and reflective, The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love is a rich and provocative book."Michiko Kakutani, New York Times

-

Praise for Beautiful Maria of My Soul:Amy Tan, bestselling author of The Joy Luck Club and The Kitchen God's Wife

"I fell instantly in love with the glorious soul ofBeautiful Maria of my Soul. Hijuelos has created and brought to life two beloved characters, a heart-stealing heroine and Havana during an epoch of changing life." -

"Beautiful Maria is the Queen of the Mambo Kings! Oscar Hijuelos brings this magnificent character to life in this lyrical novel."Gay Talese, author of A Writer's Life

- On Sale

- Oct 4, 2016

- Page Count

- 496 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455561513

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use