Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

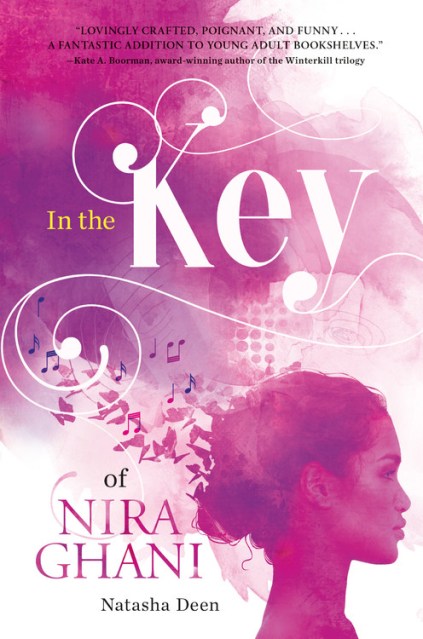

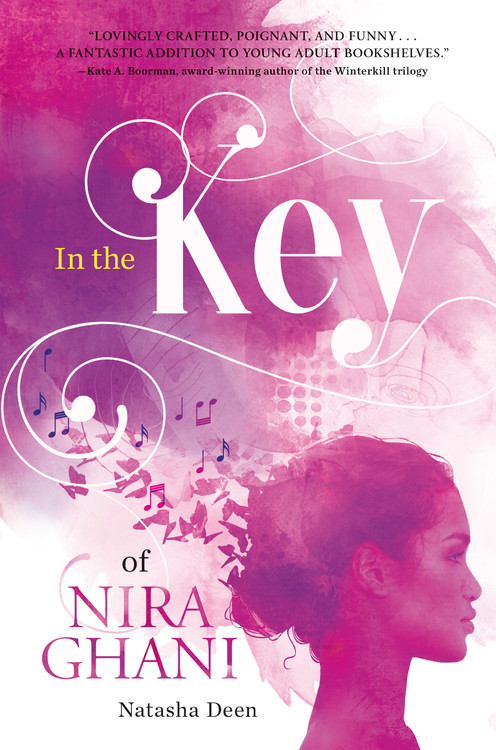

In the Key of Nira Ghani

Contributors

By Natasha Deen

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$23.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $17.99 $23.49 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $10.99 $14.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 9, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Nira Ghani has always dreamed of becoming a musician. Her Guyanese parents, however, have big plans for her to become a scientist or doctor. Nira's grandmother and her best friend, Emily, are the only people who seem to truly understand her desire to establish an identity outside of the one imposed on Nira by her parents. When auditions for jazz band are announced, Nira realizes it's now or never to convince her parents that she deserves a chance to pursue her passion.

As if fighting with her parents weren't bad enough, Nira finds herself navigating a new friendship dynamic when her crush, Noah, and notorious mean-girl, McKenzie "Mac," take a sudden interest in her and Emily, inserting themselves into the fold. So, too, does Nira's much cooler (and very competitive) cousin Farah. Is she trying to wiggle her way into the new group to get closer to Noah? Is McKenzie trying to steal Emily's attention away from her? As Farah and Noah grow closer and Emily begins to pull away, Nira's trusted trumpet "George" remains her constant, offering her an escape from family and school drama.

But it isn't until Nira takes a step back that she realizes she's not the only one struggling to find her place in the world. As painful truths about her family are revealed, Nira learns to accept people for who they are and to open herself in ways she never thought possible.

A relatable and timely contemporary, coming-of age story, In the Key of Nira Ghani explores the social and cultural struggles of a teen in an immigrant household.

Amy Mathers Award Winner

MYRCA Award Nominee

R. Ross Arnett Award Nominee

American Library Association YALSA Quick Pick for Reluctant Readers

Red Maple Award Nominee

Red Maple Honour Book

Barnes & Noble’s Top 25 Most Anticipated Own Voices Novels

Chapters-Indigo Most Anticipated Teen Books

Junior Library Guild Selection

CCBC Best Pick for Kids & Teens

CCBC Red Leaf Literature

OLA White Pine Teen Committee Summer Reading List

Genre:

-

"In the Key of Nira Ghani is the YA novel today's readers have been waiting for.... This work poignantly explores the timeless storyline of defying the dreams of your parents in order to find your own path, making it a great choice for teens striving to develop their own personal identity in the face of adversity."Booklist, Starred Review

-

Mentions of everyday cultural traditions are welcome additions to this tale of a teen finding the courage to stand up for her individuality while honoring the people she comes from. A charming, honest, and heartwarming story that will leave readers satiated and happy.Kirkus Reviews

-

This bittersweet, humorous coming-of-age story represents a common struggle faced by children of immigrants: wanting to be seen and loved for who they really are.The Horn Book

-

A love-letter to complicated families and the challenges of the immigrant experience, In the Key of Nira Ghani is sparkling, soaring, and soulful--a devastatingly authentic, pitch-perfect story of longing and belonging.Alison Hughes, author of Hit the Ground Running

-

Lovingly-crafted, poignant, and funny; In the Key of Nira Ghani is the story of a girl striving to find her melody amidst a cacophony of cultural expectations, traditional parents, and her own self-doubt. Nira's wry observations will delight you; her deep yearning will capture your heart. A fantastic addition to young adult bookshelves.Kate A Boorman, award-winning author of the Winterkill trilogy

-

Moving, uplifting, and written with a sharp sense of humor that had me laughing out loud more than once.Robin Stevenson, author of A Thousand Shades of Blue

-

In the Key of Nira Ghani is a complex coming-of-age story that will resonate with all ages.Jacqueline Guest, author of The Comic Book War

-

Witty, funny, and heartbreaking, often all on the same page. Expect to read this one all in one sitting.Lisa J. Lawrence, author of Trail of Crumbs

-

A younger high school crowd with an appetite for snark will enjoy the bumpy road that Nira walks toward authenticity, love, and true friendship.School Library Journal

- On Sale

- Apr 9, 2019

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press Kids

- ISBN-13

- 9780762465477

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use