Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

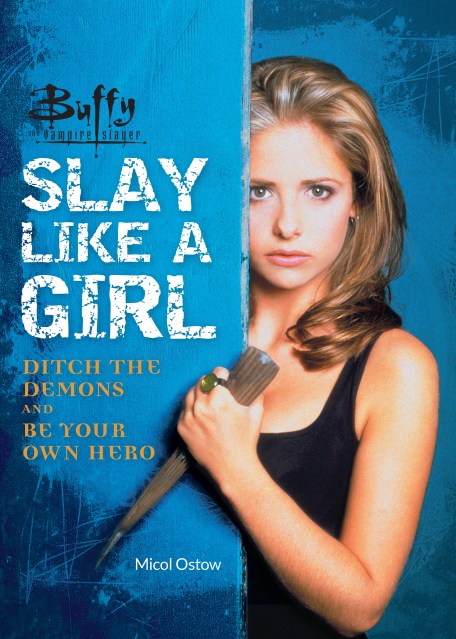

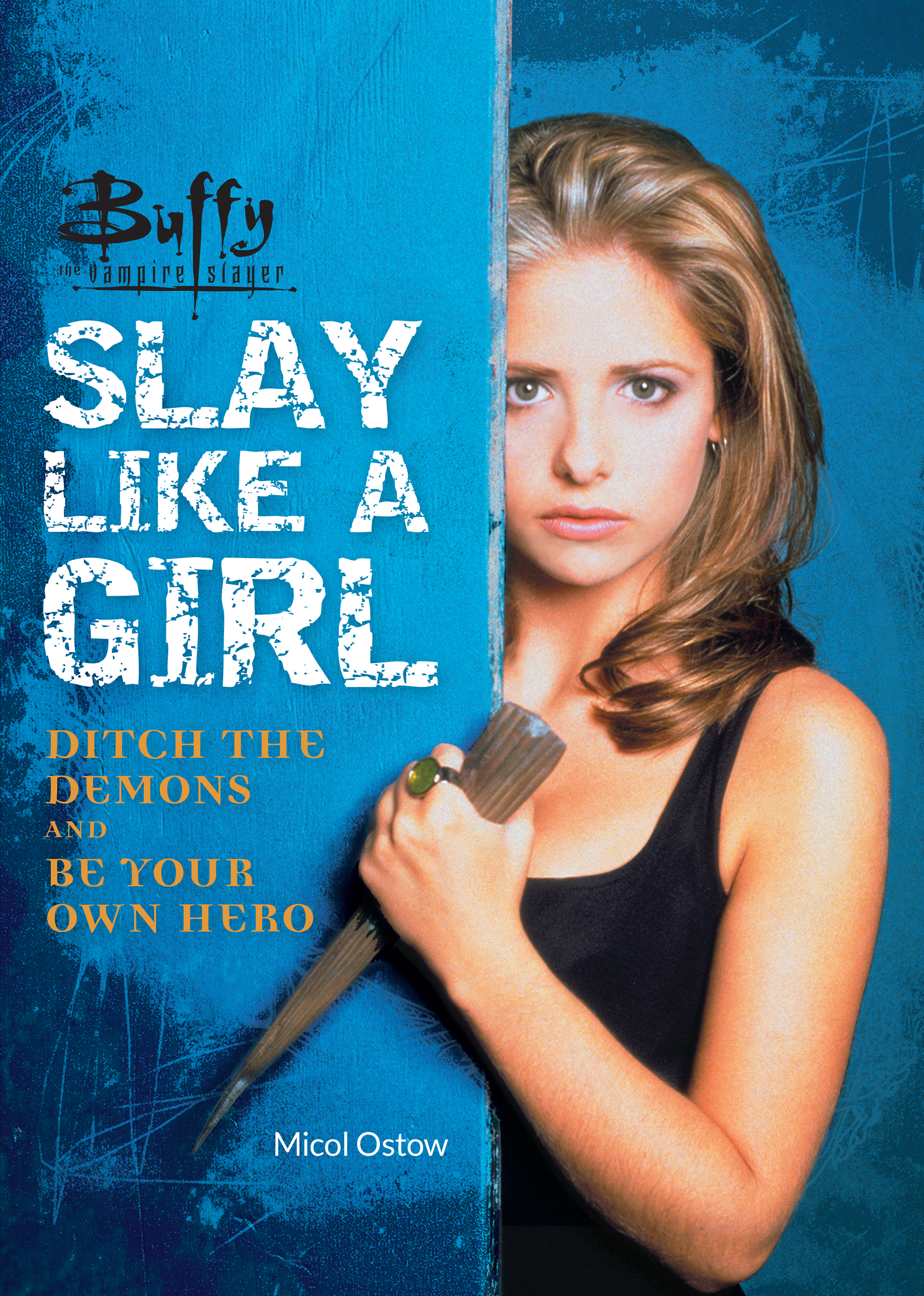

Buffy the Vampire Slayer: Slay Like a Girl

Ditch the Demons and Be Your Own Hero

Contributors

By Micol Ostow

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Calendar $20.00 $26.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $12.95 $16.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 8, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Are you ready to be strong? Inspired by the badass ladies of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, this is the ultimate guide for living your most killer life.

Buffy turned tired, sexist tropes on their head when it debuted in the ’90s and introduced a truly empowered heroine (and a kickass roster of female supporting roles). So who better than Buffy and her fellow babes — Willow, Cordelia, Faith, Anya, Tara, and others — to teach us how to slay our own personal demons? The ladies have much to offer in terms of savvy insights, observations, and life lessons.

Slay Like a Girl examines the groundbreaking female paradigms presented in Buffy and offers digestible, entertaining lessons for slaying at work, in love, and beyond. Also featuring photos from the show, memorable quotes, and fresh input from modern ladies who slay, Slay Like a Girl is an indispensable handbook for fans, feminists, and all other fierce folk.

Buffy turned tired, sexist tropes on their head when it debuted in the ’90s and introduced a truly empowered heroine (and a kickass roster of female supporting roles). So who better than Buffy and her fellow babes — Willow, Cordelia, Faith, Anya, Tara, and others — to teach us how to slay our own personal demons? The ladies have much to offer in terms of savvy insights, observations, and life lessons.

Slay Like a Girl examines the groundbreaking female paradigms presented in Buffy and offers digestible, entertaining lessons for slaying at work, in love, and beyond. Also featuring photos from the show, memorable quotes, and fresh input from modern ladies who slay, Slay Like a Girl is an indispensable handbook for fans, feminists, and all other fierce folk.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 8, 2019

- Page Count

- 176 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762468409

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use