Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

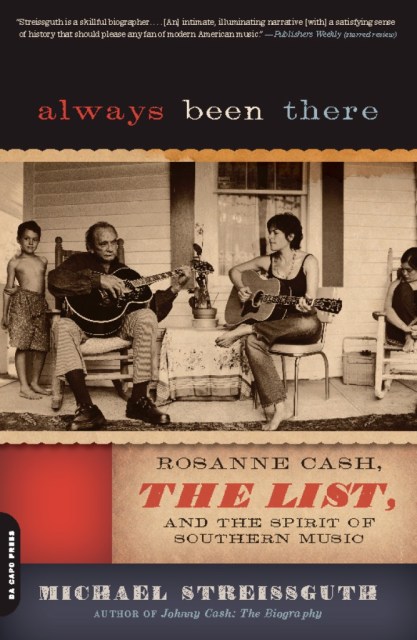

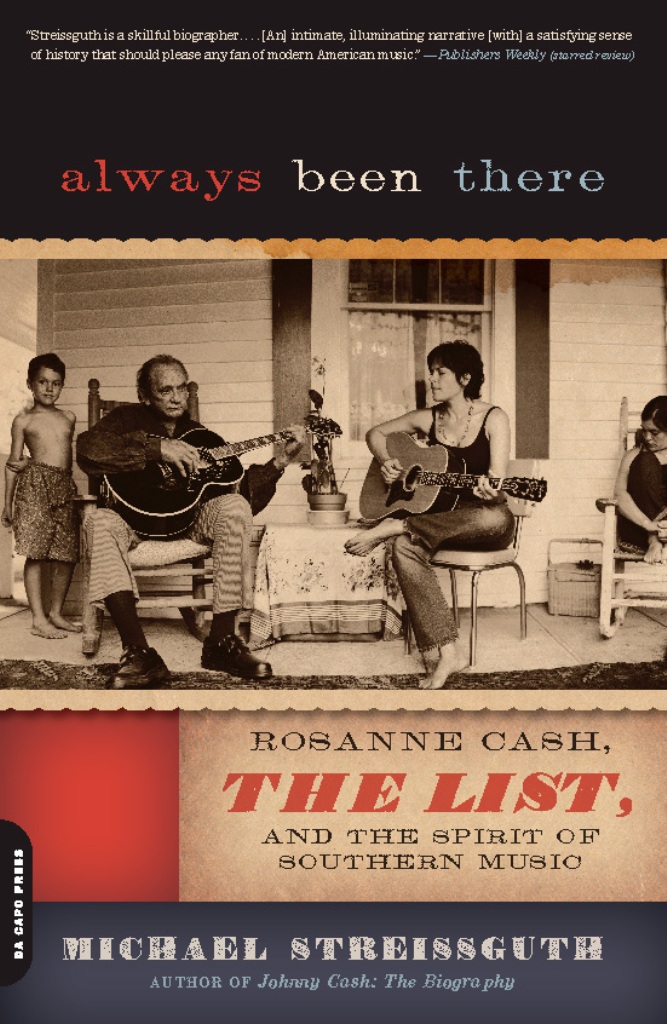

Always Been There

Rosanne Cash, The List, and the Spirit of Southern Music

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 15, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Based on original interviews conducted in the studio, at home in New York City, and on tour in Europe, Always Been There documents a pivotal episode in Rosanne Cash’s long and fascinating career. As she, along with producer and husband John Leventhal, painstakingly reconstructs what songs made “the list” and why, we gain an unmatched understanding of a longer musican continuium that includes the Carter Family and other fabled names of the Southern pantheon and their influence on her music and writing. We also see how Leventhal’s talents as an arranger and musician pair with Rosanne’s searching vocal performances to make these old songs new again.

Always Been There tracks Rosanne Cash’s singular and storied career from her early commercial hits with albums like King’s Record Shop through her controversial split with Nashville tradition on albums like the mercurial Interiors to the sublime Black Cadillac. It paints an unforgettable portrait of Rosanne confronting music-making in the aftermath of serious brain surgery, her lifelong search for her legacy, and her unique creative partnerships.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Dec 15, 2009

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306819261

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use