Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

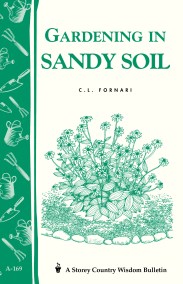

Making Ice Cream and Frozen Yogurt

Storey's Country Wisdom Bulletin A-142

Contributors

By Maggie Oster

Formats and Prices

Price

$3.95Price

$5.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $3.95 $5.95 CAD

- ebook $3.99 $4.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 8, 1995. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Since 1973, Storey’s Country Wisdom Bulletins have offered practical, hands-on instructions designed to help readers master dozens of country living skills quickly and easily. There are now more than 170 titles in this series, and their remarkable popularity reflects the common desire of country and city dwellers alike to cultivate personal independence in everyday life.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 8, 1995

- Page Count

- 32 pages

- Publisher

- Storey

- ISBN-13

- 9780882664149

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use