Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

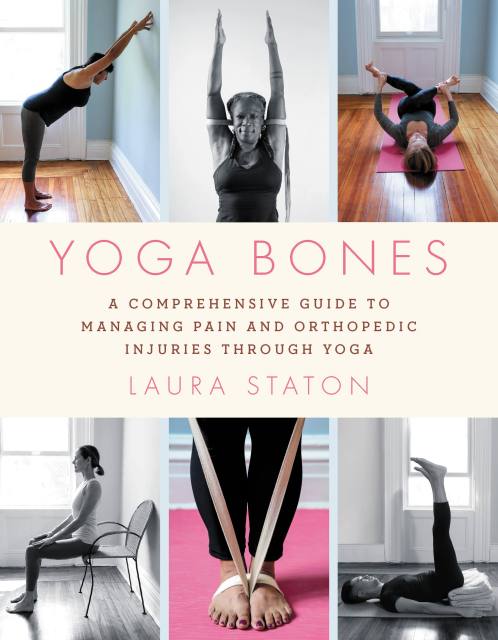

Yoga Bones

A Comprehensive Guide to Managing Pain and Orthopedic Injuries through Yoga

Contributors

By Laura Staton

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 5, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Create a personalized, therapeutic, yoga-based plan to heal bodily pain and get you back to living the life you deserve.

If you are one of the millions of people who suffer from an orthopedic condition, you understand the impact on your daily life. From neck pain to knee replacement and everything in between, Laura Staton uses yoga as a roadmap to restore function and life balance. This invaluable guide helps you explore your mind-body connection to manage your discomfort and find long-term healing, increase strength, and decrease pain.

Expertly organized by orthopedic conditions including herniated disks in the back or neck, shoulder syndromes, hip replacements, and more, each chapter includes a curated menu of therapeutic poses with descriptions, photographs, and illustrations. Yoga Bones is accessible to all ages and abilities, with yoga that is easily adaptable to different levels of fitness and function. With a holistic and gentle approach, Staton provides a bridge between mainstream medical practices and mindful healing. You don't have to suffer through pain or learn to endure it; you can find ways to strengthen your body and your overall health.

Genre:

-

"Yoga Bones is a knowledgeable and insightful guide for anyone interested in the interface of Western medicine and Eastern yoga practices, and how they combine to treat many physical conditions and create holistic well-being. Staton's experience as both an occupational therapist and a yoga therapist comes together in a treasure trove of accessible and helpful guidance. I love this book, and I recommend it to professionals, and to anyone who is seeking help with issues ranging from foot to neck pain, and everything in between."Liz Owen, yoga therapist and coauthor of The Yoga Effect and Yoga for a Healthy Lower Back

-

"Laura's unique and well-received individualized yoga sessions have been enormously beneficial to appropriate patients as an adjunct to their rehabilitation programs. She applies her expertise to Yoga Bones, which provides additional treatment options that patients can use, with the advice of their physicians, to help alleviate their symptoms."Jeffrey B. Weinberg, MD, chairman, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Staten Island University Hospital

-

“This book is clear and informative; its author is anatomically sophisticated, and has crucial knowledge of how changes in anatomy translate into functional problems. With equal clarity she sketches out how to take care of these problems."Loren Fishman, MD, Columbia University Medical School, B.Phil.,(oxon.)

- On Sale

- Jan 5, 2021

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Go

- ISBN-13

- 9780306846250

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use