Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

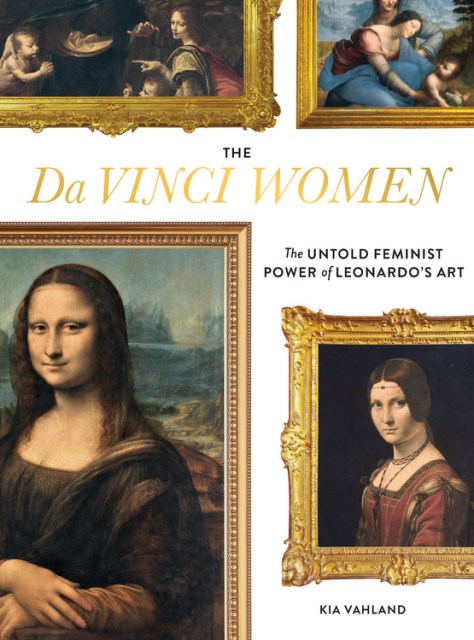

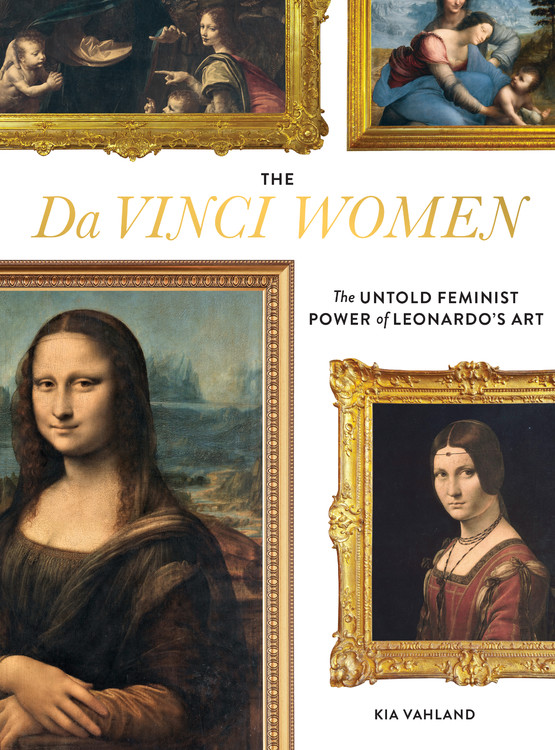

The Da Vinci Women

The Untold Feminist Power of Leonardo's Art

Contributors

By Kia Vahland

Formats and Prices

Price

$29.99Price

$37.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.99 $37.99 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 25, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This new biographical look at Leonardo da Vinci explores the Renaissance master’s groundbreaking portrayal of women which forever changed the way the female form is depicted.

Leonardo da Vinci was a revolutionary thinker, artist, and inventor who has been written about and celebrated for centuries. Lesser known, however, is his revolutionary and empowering portrayal of the modern female centuries before the first women’s liberation movements.

Before da Vinci, portraits of women in Italy were still, impersonal, and mostly shown in profile. Leonardo pushed the boundaries of female depiction having several of his female subjects, including his Mona Lisa, gaze at the viewer, giving them an authority which was withheld from women at the time.

Art historian and journalist Kia Vahland recounts Leonardo’s entire life from April 15, 1452, as a child born out of wedlock in Vinci up through his death on May 2, 1519, in the French castle of von Cloux. Included throughout are 80 sketches and paintings showcasing Leonardo’s approach to the female form (including anatomical sketches of birth) and other artwork as well as examples from other artists from the 15th and 16th centuries. Vahland explains how artists like Raphael, Giorgione, and the young Titan were influenced by da Vinci’s women while Michelangelo, da Vinci’s main rival, created masculine images of woman that counters Leonardo’s depictions.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Feb 25, 2020

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780762496433

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use