Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

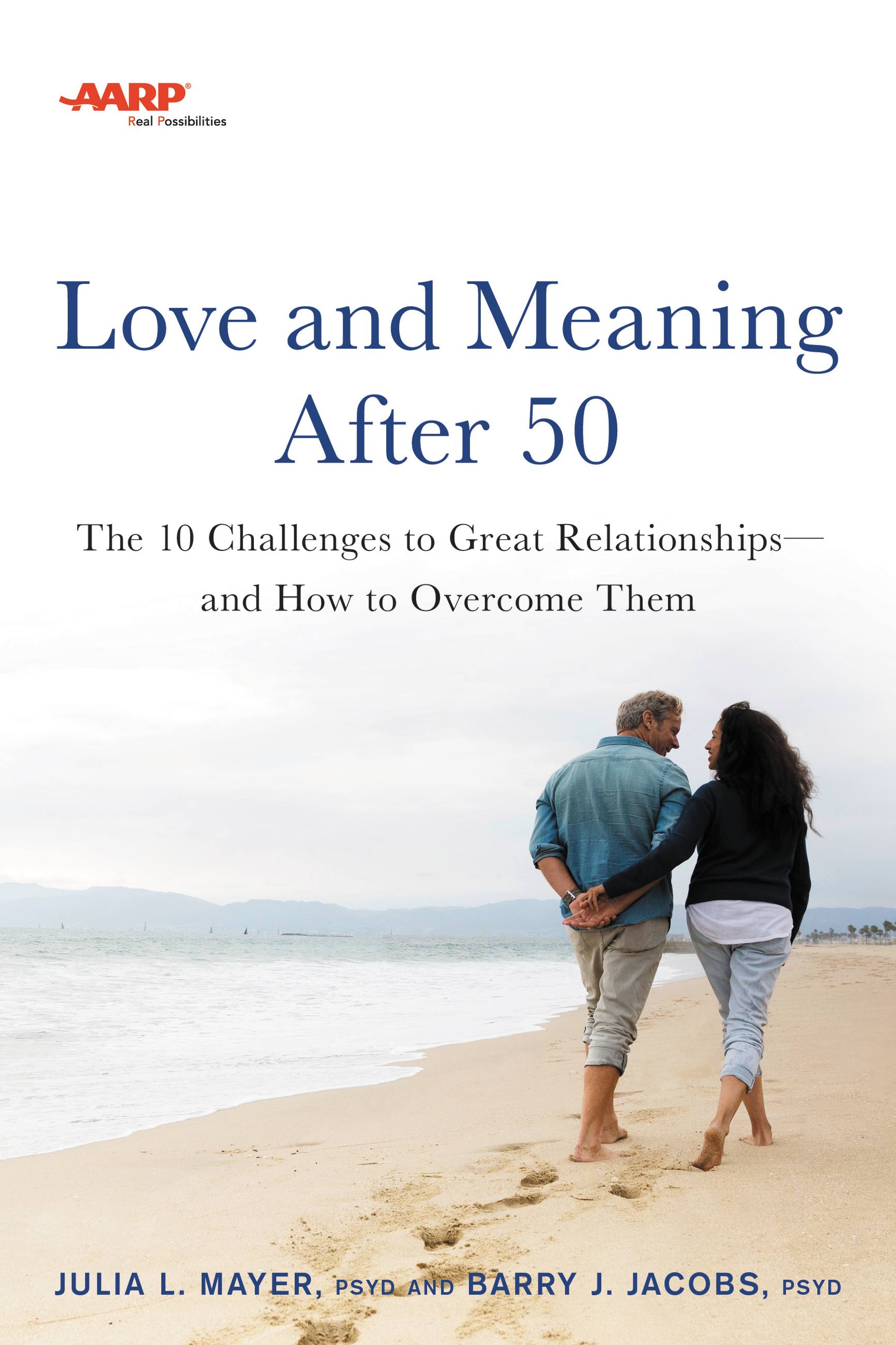

AARP Love and Meaning after 50

The 10 Challenges to Great Relationships—and How to Overcome Them

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 4, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Sustain loving relationships and set yourself up for emotional wellness in your fifties, sixties, and beyond with this valuable collection of advice from two psychology experts.

“Drs. Mayer and Jacobs use their clinical wisdom and story-telling abilities to bring to life the challenges for couples as they age. Their advice will help strengthen long-term relationships to combat the rising trend of Gray Divorce.”

–Janis Abrahms Spring, PhD, author of After the Affair and Life with Pop

With couples divorcing at higher rates than any generation before, and longer lifespans leaving people unwilling to settle for an unsatisfying partner, it’s more important than ever to refocus and strengthen your relationship. The only question is: how?

In AARP Love and Meaning after 50, husband-wife psychologist team Julia Mayer and Barry Jacobs — with 50+ years of experience between them — identify the 10 most common challenges to sustain loving relationships:

The Empty Nest * Extended Family * Finances * Infidelity

Retirement * Downsizing and Relocating * Sex

Health Concerns * Caregiving * Loss of Loved Ones

AARP Love and Meaning after 50 offers insights and anecdotes, do it yourself assessments and follow-up exercises, and tips for connecting through the difficult times. With this book, you’ll find deeper meaning and greater satisfaction for the decades ahead–together.

Genre:

-

"Drs. Mayer and Jacobs use their clinical wisdom and story-telling abilities to bring to life the challenges for couples 50-plus. Their advice will help strengthen long-term relationships to combat the rising trend of Gray Divorce."Janis Abrahms Spring, PhD, author of After the Affair and Life with Pop

-

"A must-read for anyone over 50 who is married or wants to be. I wish my parents had read this book when they were in their 50s! It's a practical, hopeful guide to renegotiating and reinvigorating your relationship. It will save a lot of marriages, because it will really help you and your spouse talk to each other."Stephen Fried, New York Times bestselling author of Husbandry: Sex, Love and Dirty Laundry: Inside the Minds of Married Men and Rush: Revolution, Madness & the Visionary Doctor Who Became a Founding Father

-

"A beautifully written guide for couples who want inspiration, a refresher, or a reboot after the kids are gone."William J. Doherty, Ph.D., Professor of Family Social Science, University of Minnesota, and author of Take Back Your Marriage

-

"Julia Mayer and Barry Jacobs have given us an eminently practical guide to maintaining connection and re-establishing intimacy for couples over 50. They provide engaging descriptions and clear step-by-step guidance to help couples forge deeper meaning and greater closeness. As the percentage of Americans over 65 continues to grow, this will become an increasingly important and relevant book for an ever-larger segment of our population."Dr. Patricia Papernow, author of Surviving and Thriving in Stepfamily Relationships: What Works and What Doesn't, and, with Karen Bonnell, The Stepfamily Handbook: From Dating, to Getting Serious to Forming a "Blended Family"

- On Sale

- Aug 4, 2020

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Go

- ISBN-13

- 9780738286174

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use