Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

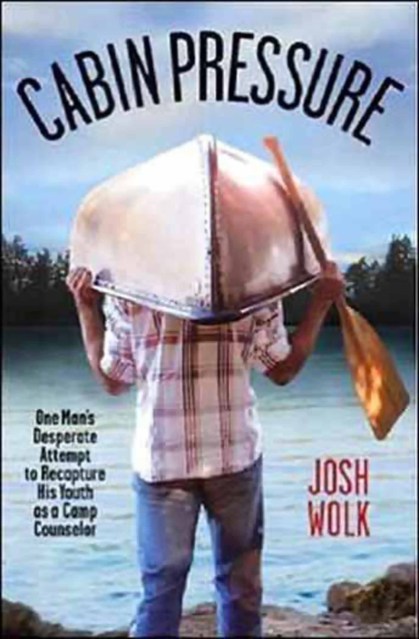

Cabin Pressure

One Man's Desperate Attempt to Recapture His Youth as a Camp Counselor

Contributors

By Josh Wolk

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $10.99 $13.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 5, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Three months before getting married at age thirty-four, Josh Wolk decides to treat himself to a “farewell to childhood” extravaganza: one last summer working at the beloved Maine boys camp where he spent most of the eighties. And there he finds out that there’s no better way to see how much you’ve changed than to revisit a place that hasn’t changed at all.

In these eight hilarious, uncomfortable, enlightening weeks, Josh readjusts to life teaching swimming and balancing on a thin metal cot in a cabin of shouting, wrestling, wet-willie-dispensing fourteen-year-olds who, contrary to the warnings of doomsaying sociologists, he finds indistinguishable from the rowdy fourteen-year-olds of his day in any way other than their haircuts. With his old camp friends gone, he finds himself working alongside guys who used to be his campers. Moments of feeling cripplingly old are offset by the corrosive insecurities of his youth when he’s paired in the cabin with Mitch, the forty-two-year-old jack-of-all-extreme-sports whose machismo intimidated Josh so much fifteen years earlier, and whom their current campers idolize. And throughout all this disorienting regression, Josh’s telephone conversations with his fiance, Christine, grow increasingly intense as their often-comical discussions over the wedding become a flimsy cover for her worries that he’s not ready to relinquish his death-grip on the comforts of the past.

A hilarious and insightful look at the tenacious power of nostalgia, the glory of childhood, and the nervous excitement of taking a leap to the next unknown stage in life, Cabin Pressure will appeal to anyone who’s ever been young, wishes he was young again, but knows deep down it probably isnt a good idea.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jun 5, 2007

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781401388362

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use