Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

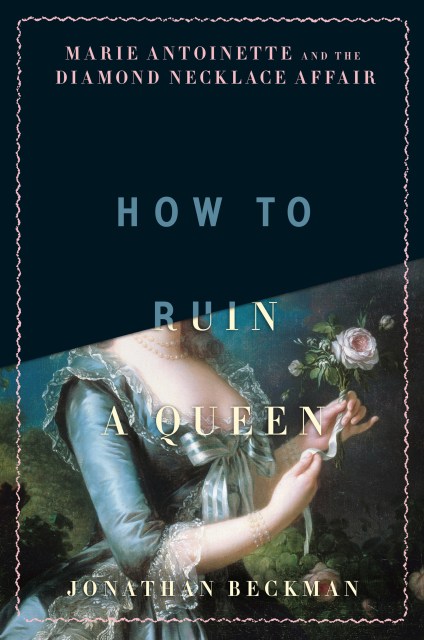

How to Ruin a Queen

Marie Antoinette and the Diamond Necklace Affair

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Format

Format:

ebook $14.99This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 2, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In How to Ruin a Queen, award-winning author Jonathan Beckman tells of political machinations and enormous extravagance; of kidnappings, prison breaks, and assassination attempts; of hapless French police in disguise, reams of lesbian pornography, and a duel fought with poisoned pigs. It is a detective story, a courtroom drama, a tragicomic farce, and a study of credulity and self-deception in the Age of Enlightenment.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 2, 2014

- Page Count

- 408 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306823565

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use