Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

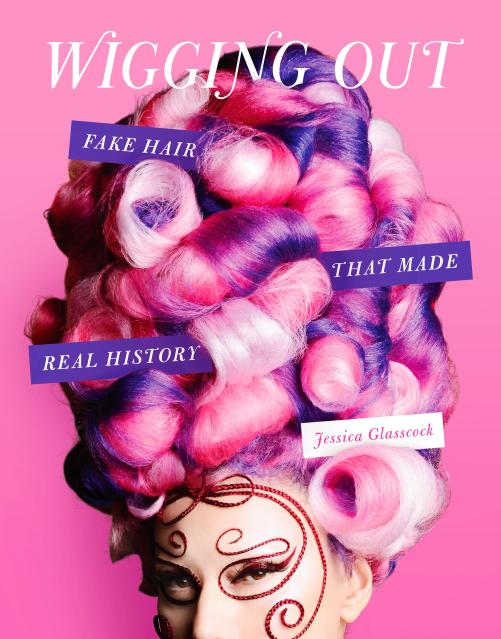

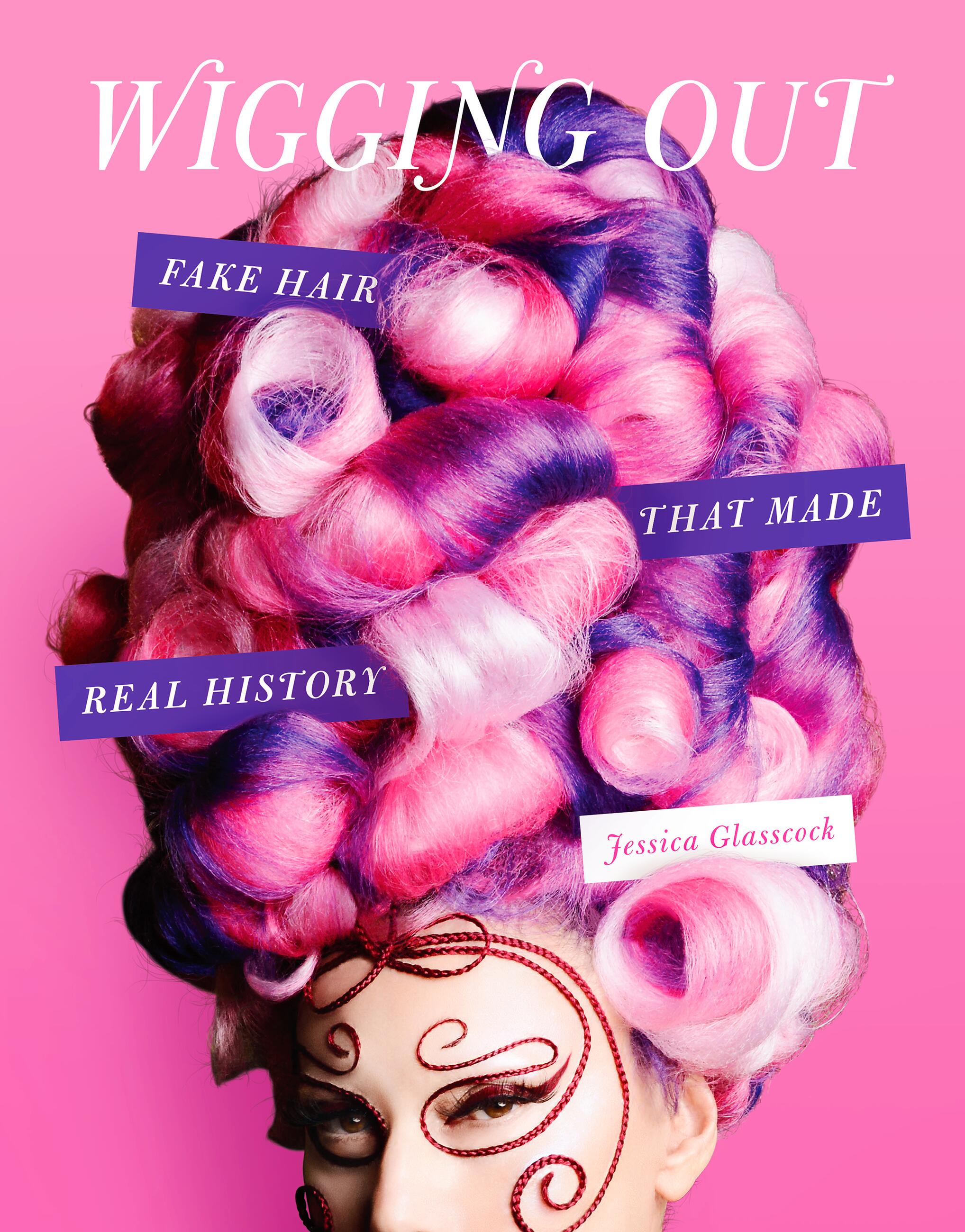

Wigging Out

Fake Hair That Made Real History

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 18, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Starting in ancient Egypt and ending on the red carpet of the Met Gala, Wigging Out features key historical moments in fashion set alongside spectacular images of real and synthetic wigs worn by everyone from Roman emperors and nineteenth-century Gibson Girls to twenty-first-century drag queens and London street punks. Including interviews with modern wigmakers, stylists, and braiders, Wigging Out takes readers on a joyful romp through fake-hair history.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 18, 2023

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780762481477

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

LOOK INSIDE

Q&A with Jessica Glasscock, author of Wigging Out

Where did the idea for this book come from?

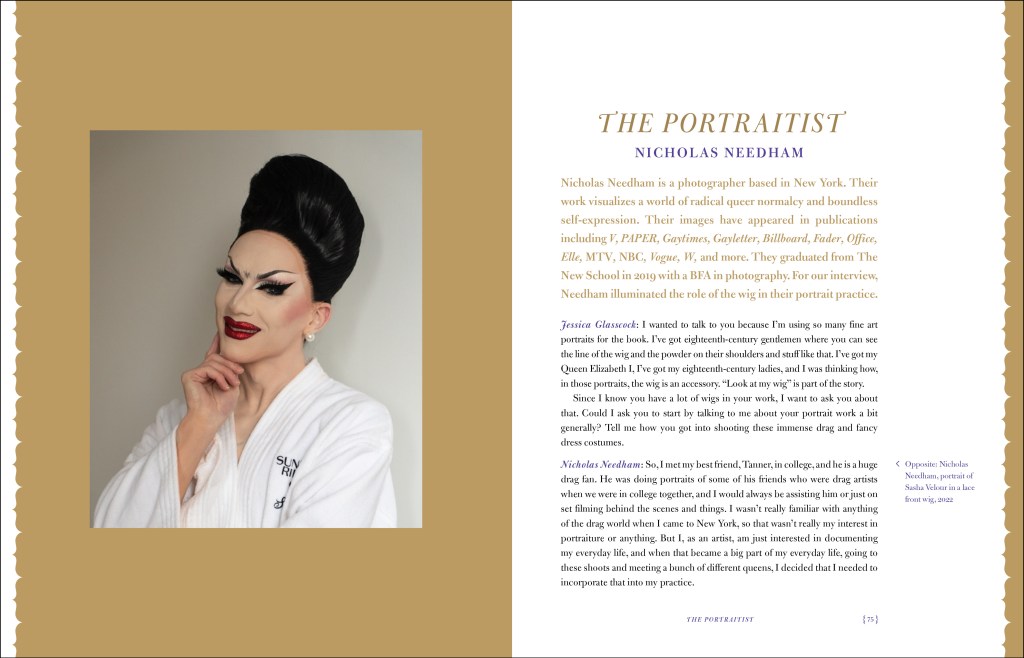

I’ve always been into the idea of fashion as a total work of art – it’s more than just dress and “genius” designers. After Making a Spectacle (on eyewear), my editor suggested wigs. I jumped on it because there is such an array of great creatives who have been devoted to the fabulous coif. I knew I could write an expansive history, since the story runs from Egypt to the Paris runway.

How did wigs ascend to fashion royalty?

When I talk about wigs, I have this tendency to use a word that gets worn out: iconic. But it very much applies! The key to wig use by royalty and other socially spectacular figures was the ability to create an increased profile (literally!).

What’s the greatest wig trend in the 21st century?

There are two seemingly opposite trends in tandem: increased realness combined with obvious artificiality – like the integration of a seamlessly applied lace front for maximum realism on a wig with color that nature could never execute.

Also by Jessica Glasscock

The power of glasses to convey a range of vivid messages about their wearers have made them into a billion-dollar business that appeals to cool kids and rock stars, and those who want to be like them, but the fashionable history of eyeglasses is fraught with anxiety and drama. At the beginning of the 20th century, the assessment in Vogue and Harper's Bazaar was that spectacles were "invariably disfiguring." Invisibility was the best option, and glasses were only to be put on once the lights at the opera went dark.

While variations of that glasses-shaming sentiment appeared at regular intervals over the next 100 years or so, eyeglasses continued to evolve into an endless array of shapes, colors, purposes, and personalities. Once sunglasses took off in the 1930s, the magazine editorial made glasses a conspicuous part of the fashion narrative. Eyeglasses went to the ski slopes, the stables, the beach, the Havana hotel. Plastic innovations made a candy-colored rainbow of cat-eyes and "starlet" styles possible. Suddenly, everyone had the opportunity to look like Jackie O on vacation in Capri.

Making a Spectacle traces contemporary high fashion frames back to their origins: the military aviator, the glam cat eye, the nerdly Oxford, the high-tech shield, the fanciful butterfly, the lowly rimless, and other styles all make an appearance. Featuring interviews with influential designers, makers, and purveyors of glasses including Adam Selman, Kerin Rose Gold, and l.a. Eyeworks, Making a Spectacle also takes a look at today's most cutting edge eyewear, showing the reader the latest and most innovative ways to see and be seen.