Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

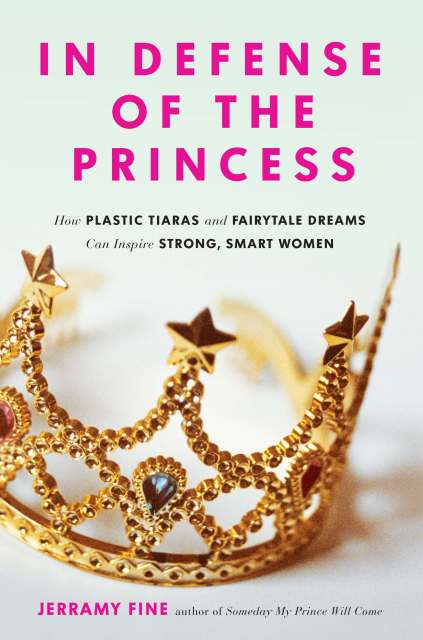

In Defense of the Princess

How Plastic Tiaras and Fairytale Dreams Can Inspire Smart, Strong Women

Contributors

By Jerramy Fine

Formats and Prices

Price

$8.99Price

$10.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $8.99 $10.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $15.00 $19.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 22, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Enter Jerramy Fine — an unabashed feminist who is proud of her life-long princess obsession and more than happy to defend it. Through her amusing life story and in-depth research, Fine makes it clear that feminine doesn’t mean weak, pink doesn’t mean inferior, and girliness is not incompatible with ambition. From 9th century Cinderella to modern-day Frozen, from Princess Diana to Kate Middleton, from Wonder Woman to Princess Leia, Fine valiantly assures us that princesses have always been about power, not passivity. And those who love them can still be confident, intelligent women.

Provocative, insightful, but also witty and personal, In Defense of the Princess empowers girls, women, and parents to dream of happily ever after without any guilt or shame.

Genre:

-

"The book serves as a reminder that feminism should provide women with the freedom to be anything they want—including princesses. Parents on all sides of the princess debate will find food for thought in this entertaining and provocative book."

--Booklist

"I love counterintuitive theories-they not only keep us on our toes and keep smugness at bay, but they provide truths hiding in plain sight. Jerramy Fine shows us-with personal insight and wit-what we kind of already knew: there's power, not weakness, in the princess fantasy."

--Sheila Weller, author of Girls Like Us and The News Sorority

- On Sale

- Mar 22, 2016

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762458783

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use