Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

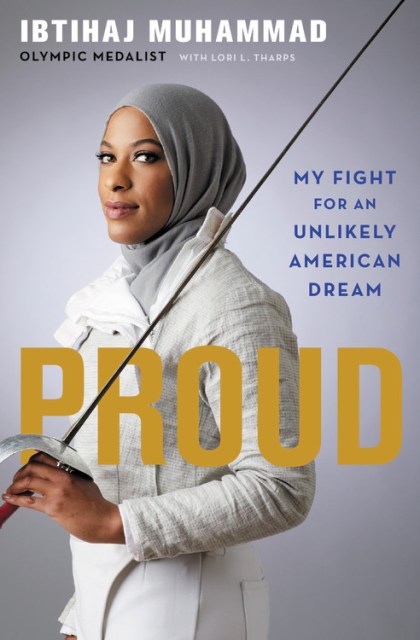

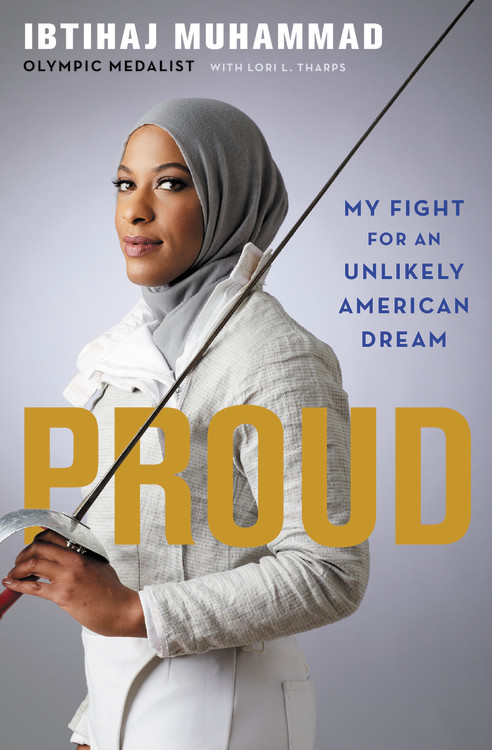

Proud

My Fight for an Unlikely American Dream

Contributors

With Lori Tharps

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 23, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

NAMED ONE OF TIME‘S 100 MOST INFLUENTIAL PEOPLE

Growing up in New Jersey as the only African American Muslim at school, Ibtihaj Muhammad always had to find her own way. When she discovered fencing, a sport traditionally reserved for the wealthy, she had to defy expectations and make a place for herself in a sport she grew to love.

From winning state championships to three-time All-America selections at Duke University, Ibtihaj was poised for success, but the fencing community wasn’t ready to welcome her with open arms just yet. As the only woman of color and the only religious minority on Team USA’s saber fencing squad, Ibtihaj had to chart her own path to success and Olympic glory.

Proud is a moving coming-of-age story from one of the nation’s most influential athletes and illustrates how she rose above it all.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 23, 2019

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316480956

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use