Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

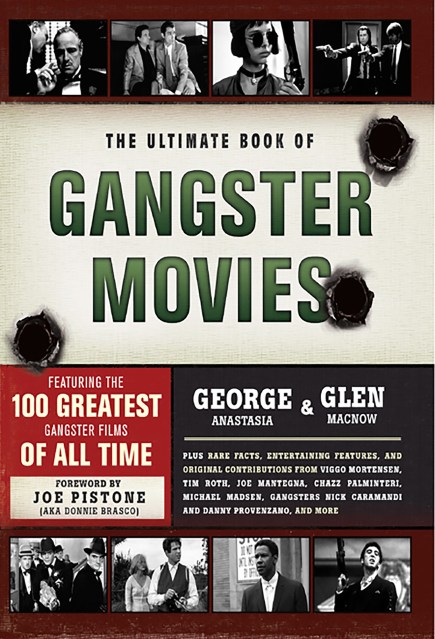

The Ultimate Book of Gangster Movies

Featuring the 100 Greatest Gangster Films of All Time

Contributors

By Glen Macnow

Foreword by Joe Pistone

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 27, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The Ultimate Book of Gangster Movies provides extensive reviews of the Top 100 gangster films of all time, including sidebars like “Reality Check,” “Hit and Miss,” “I Know That Guy,” “Body Count,” and other fun and informative features. Also included are over a dozen stand-alone chapters such as Sleeper “Hits,” “Fugazi” Flops, Guilty Pleasures, Lost Treasures, Q&A Interviews with top actors and directors (including Chazz Palinteri, Michael Madsen, Joe Mantagna, and more), plus over 50 compelling photographs.

Foreword by Joe Pistone, the FBI agent and mob infiltrator who wrote the bestselling book and acclaimed movie, Donnie Brasco.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 27, 2011

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762443703

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use