Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

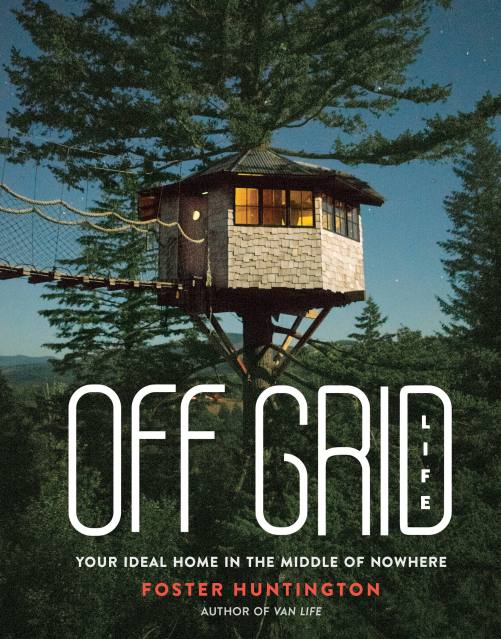

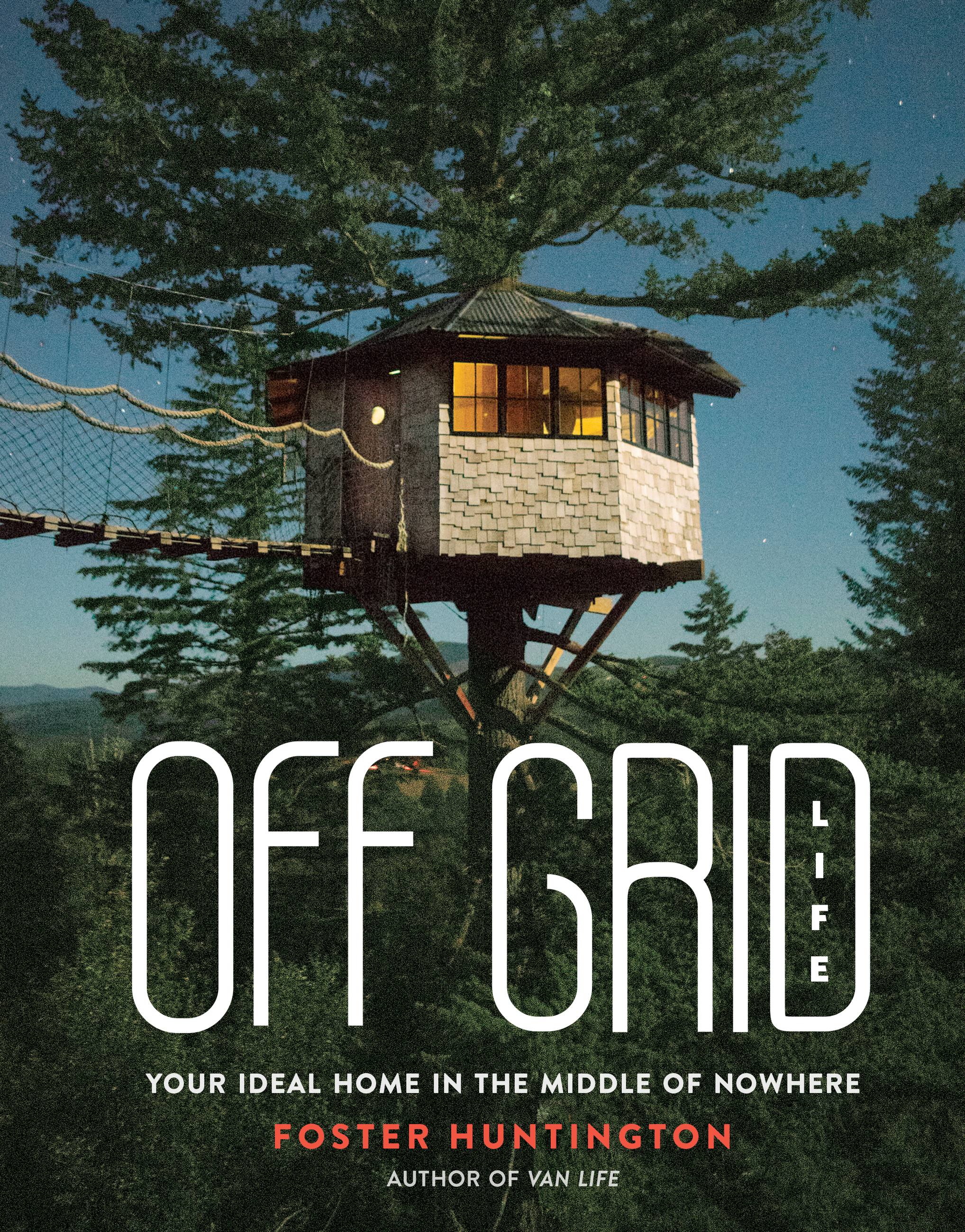

Off Grid Life

Your Ideal Home in the Middle of Nowhere

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 27, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

After spending three years on the road living in a camper van, Foster Huntington, author of Van Life, continued his unconventional lifestyle by building a two-story treehouse. Foster, like many others, are finding tranquility and adventure in living off the grid in unconventional homes.

Organized into sections like tree houses, tiny houses, shipping containers, yurts, boathouses, barns, vans, and more, Off Grid Life features 250 aspirational photographs in enviable settings like stunning beaches, dramatic mountains, and picturesque forests. Also included are images of fully designed interiors with kitchens and sleeping quarters as well as interviews with solo dwellers, couples, and families who are living this new American dream.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 27, 2020

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780762497928

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use