Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

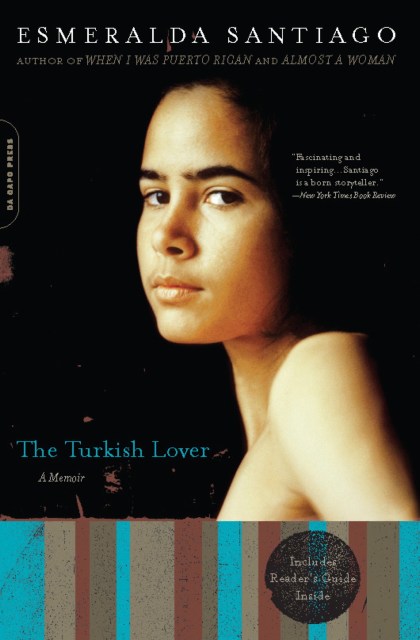

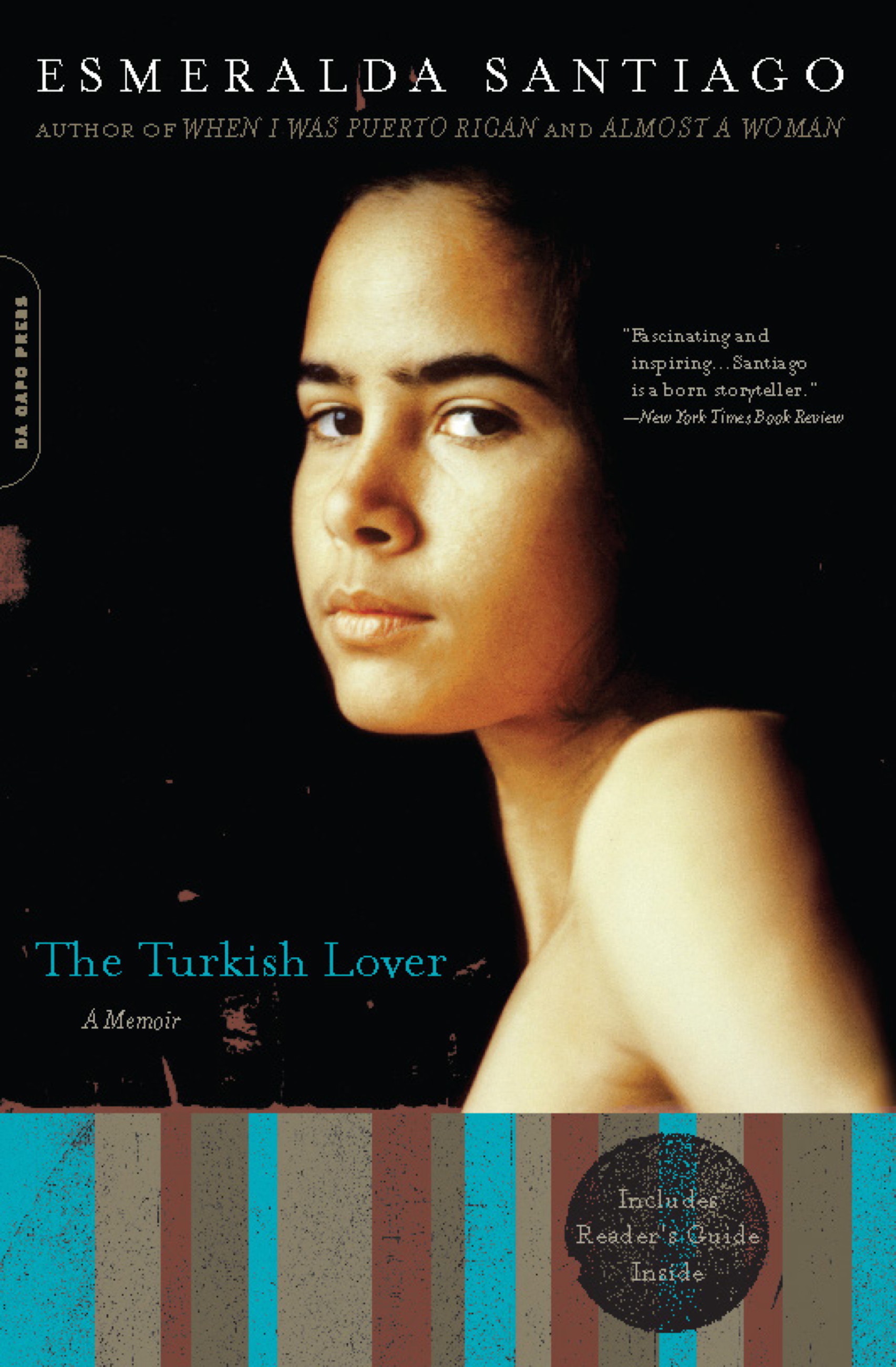

The Turkish Lover

A Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 17, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Enthralled admirers of Esmeralda Santiago’s memoirs of her childhood have yearned to read more. Now, in The Turkish Lover, Esmeralda finally breaks out of the monumental struggle with her powerful mother, only to elope into the spell of an exotic love affair. At the heart of the story is Esmeralda’s relationship with “the Turk,” a passion that gradually becomes a prison out of which she must emerge to become herself. The expansive humanity, earthy humor, and psychological courage that made Esmeralda’s first two books so successful are on full display again in The Turkish Lover.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 17, 2009

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786738335

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use