Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

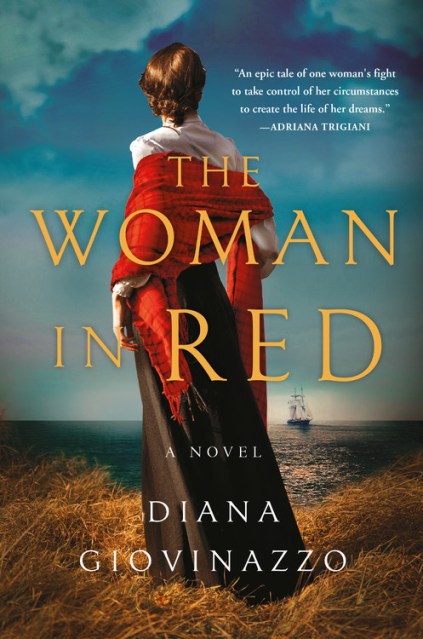

The Woman in Red

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 4, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Experience the "epic tale of one woman's fight . . . to create the life of her dreams" in this sweeping novel of Anita Garibaldi, a 19th century Brazilian revolutionary who loved as fiercely as she fought for freedom (Adriana Trigiani).

Swept into a passionate affair with the idolized mercenary, Anita's life is suddenly consumed by the plight to liberate Southern Brazil from Portugal—a struggle that would cost thousands of lives and span almost ten bloody years. Little did she know that this first taste of revolution would lead her to cross oceans, traverse continents, and alter the course of her entire life—and the world.

At once an exhilarating adventure and an unforgettable love story, The Woman in Red is a sweeping, illuminating tale of the feminist icon who became one of the most revered historical figures of South America and Italy.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 4, 2020

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538717417

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use