Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

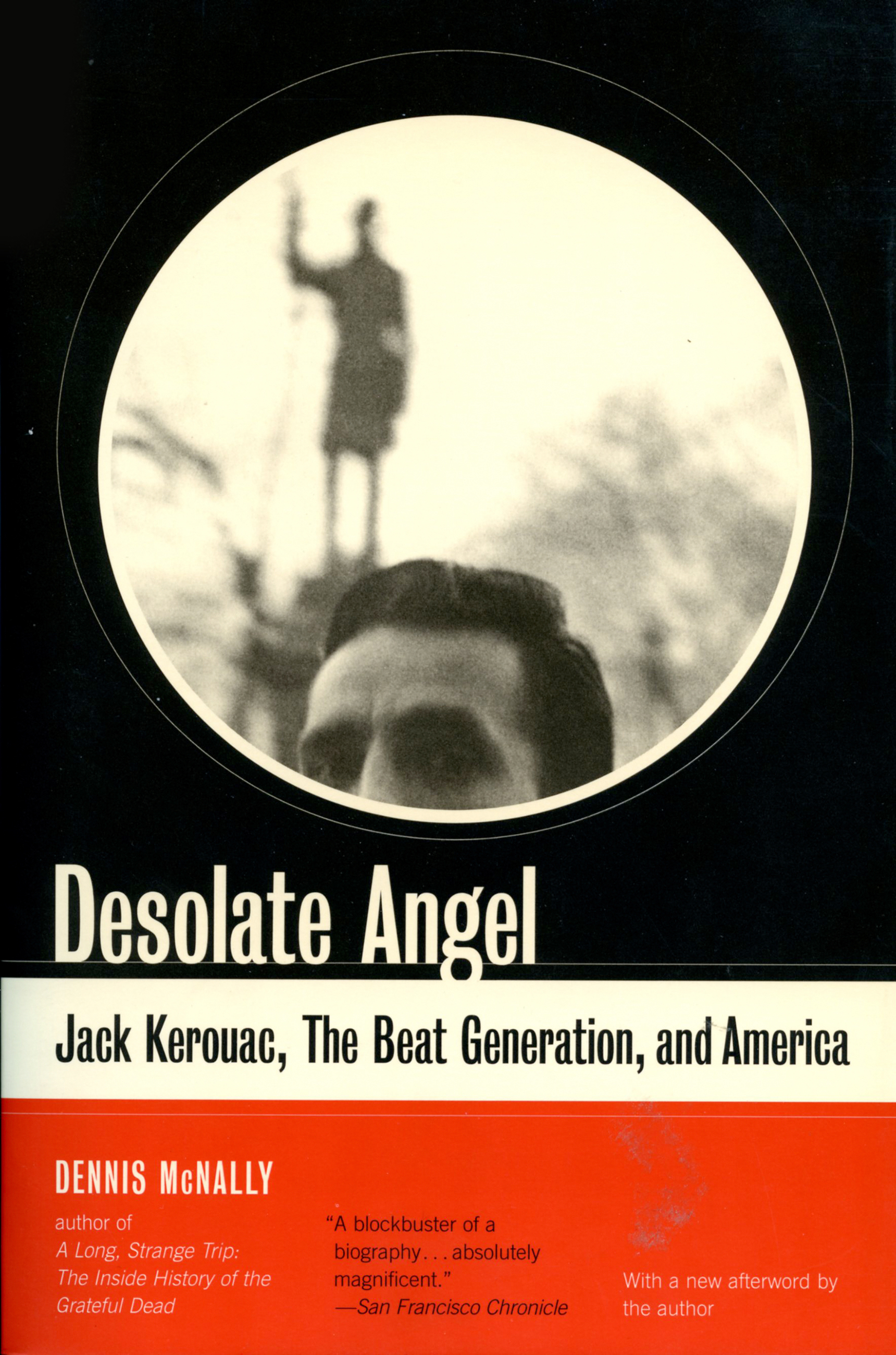

Desolate Angel

Jack Kerouac, The Beat Generation, And America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook (Digital original) $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 24, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Jack Kerouac–“King of the Beats,” unwitting catalyst for the ’60s counterculture, groundbreaking author–was a complex and compelling man: a star athlete with a literary bent; a spontaneous writer vilified by the New Critics but adored by a large, youthful readership; a devout Catholic but aspiring Buddhist; a lover of freedom plagued by crippling alcoholism.

Desolate Angel follows Kerouac from his childhood in the mill town of Lowell, Massachusetts, to his early years at Columbia where he met Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, and Neal Cassady, beginning a four-way friendship that would become a sociointellectual legend. In rich detail and with sensitivity, Dennis McNally recounts Kerouac’s frenetic cross-country journeys, his experiments with drugs and sexuality, his travels to Mexico and Tangier, the sudden fame that followed the publication of On the Road, the years of literary triumph, and the final near-decade of frustration and depression.

Desolate Angel is a harrowing, compassionate portrait of a man and an artist set in an extraordinary social context. The metamorphosis of America from the Great Depression to the Kennedy administration is not merely the backdrop for Kerouac’s life but is revealed to be an essential element of his art . . . for Kerouac was above all a witness to his exceptional times.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 24, 2020

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306875205

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use