Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

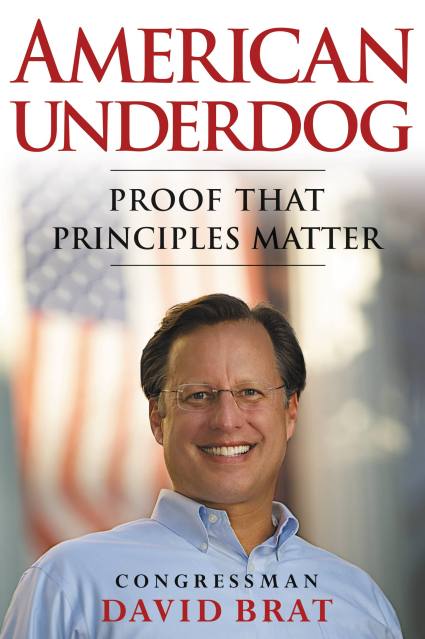

American Underdog

Proof That Principles Matter

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.00 $32.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 28, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Congressman David Brat’s odds-defying win against Eric Cantor — a triumph of a modest $200,000 campaign fund against a $5 million war chest — immediately brought David Brat, heretofore a liberal arts college economics professor, into the political limelight. Now, in his first book, American Underdog, Brat examines how we brought down the status quo by tapping into moral and economic lessons as old as our civilization and discusses how Washington can learn from history instead of ignoring it. A fighter for children, he illuminates how our current fiscal policies are selling their future, and outlines new ways to move forward with a conservative agenda that provides fairer treatment for all.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jun 28, 2016

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781455539901

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use