Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

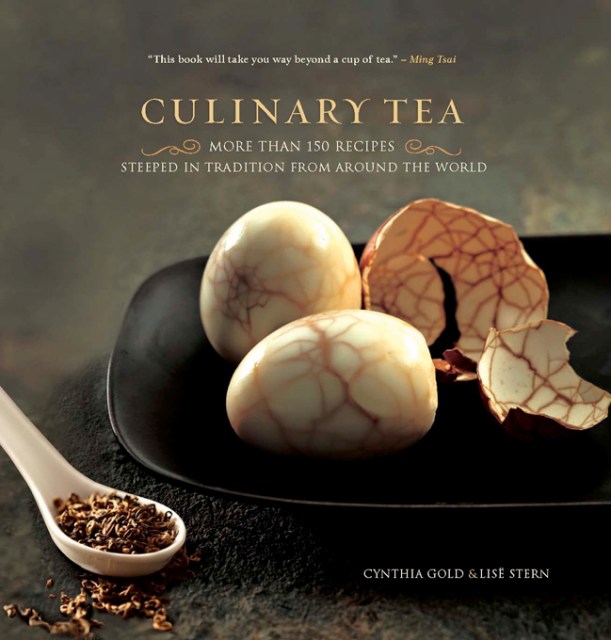

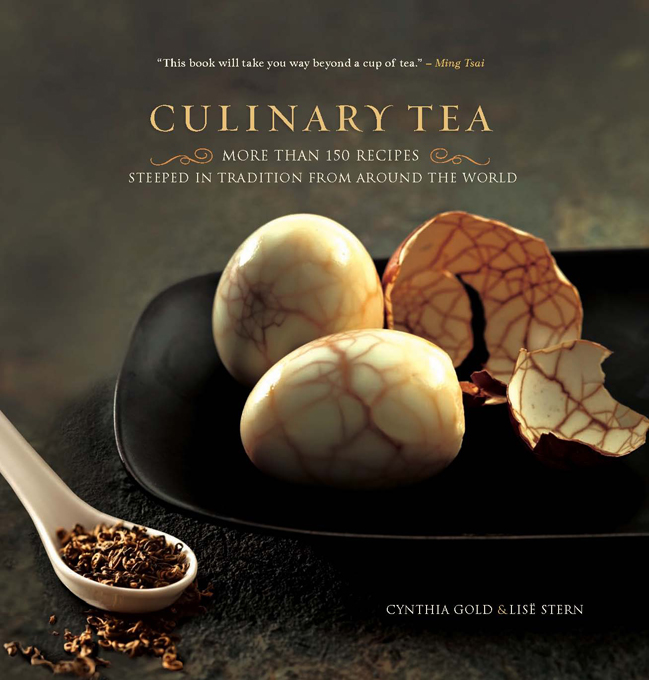

Culinary Tea

More Than 150 Recipes Steeped in Tradition from Around the World

Contributors

By Cynthia Gold

By Lise Stern

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $16.99 $21.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 7, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Tea in its many forms has been around for thousands of years, and is a burgeoning industry in many countries as the demand for specialty leaves grows. Read all about the picking and drying techniques virtually unchanged for centuries, popular growing regions in the world, and the storied past of trading.

Culinary Tea has all this, plus more than 100 recipes using everything from garden-variety black teas to exclusive fresh tea leaves and an in-depth treatment of tea cocktails. The book will include classics, such as the centuries-old Chinese Tea-Smoked Duck and Thousand-Year Old Eggs, as well as recipes the authors have developed and collected, such as Smoked Tea-Brined Capon and Assam Shortbread.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 7, 2010

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762441716

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use