Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

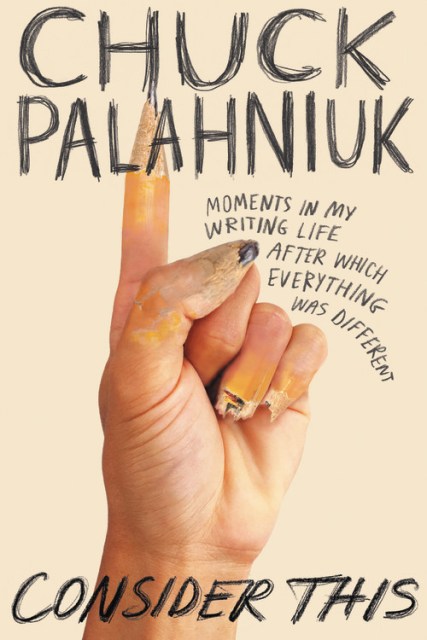

Consider This

Moments in My Writing Life after Which Everything Was Different

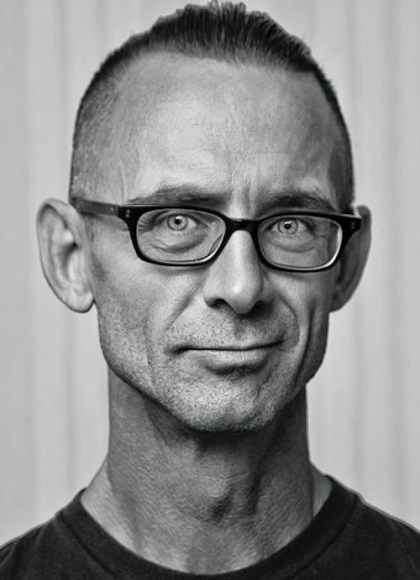

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$34.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $34.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 7, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In this spellbinding blend of memoir and insight, bestselling author Chuck Palahniuk shares stories and generous advice on what makes writing powerful and what makes for powerful writing.

With advice grounded in years of careful study and a keenly observed life, Palahniuk combines practical advice and concrete examples from beloved classics, his own books, and a “kitchen-table MFA” culled from an evolving circle of beloved authors and artists, with anecdotes, postcards from the road, and much more.

Clear-eyed, sensitive, illuminating, and knowledgeable, Consider This is Palahniuk’s love letter to stories and storytellers, booksellers and books themselves. Consider it a classic in the making.

Genre:

-

Praise for CONSIDER THISPublishers Weekly

"Reminiscent of Stephen King's On Writing in never failing to entertain while imparting wisdom, this is an indispensable resource for writers."

-

"[Palahniuk] reveals surprising humility [with] fresh and accessible ideas. Fans will appreciate the insight into his own work, especially Fight Club (1996), his tributes to friends and forebears, and how he delivers gracious and encouraging wisdom in his characteristically conversational style."Booklist

-

"For that author who wants to expand his or her horizons and try something new, Consider This by Chuck Palahniuk is the book to pick up. Laugh-out-loud funny[...]there is a world of information in this small book."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Times New Roman'}New York Journal of Books

-

"A book for those who want to learn to write dangerously, or perhaps just learn about the man who pioneered 'dangerous writing.' [It'll] inspire you try take a stab at telling your story."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Times New Roman'}Booktrib

-

"Tried-and-true practical advice for aspiring writers."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Times New Roman'}USA Today

-

"A savvy teacher. [Palahniuk's] advice is highly detailed and practical."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Times New Roman'}Kirkus

-

"Grade-A prime Chuck Palahniuk."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Times New Roman'}Publishers Weekly

-

This book from Palahniuk is insightful."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Times New Roman'}Dallas Morning News

-

PRAISE FOR CHUCK PALAHNIUK:San Francisco Chronicle

"Chuck Palahniuk's stories don't unfold. They hurtle headlong, changing lanes in threes and banging off the guard rails of modern fiction... With his love of contemporary fairytales that are gritty and dirty rather than pretty, Palahniuk is the likeliest inheritor of Vonnegut's place in American writing." -

"One of the most feverish imaginations in American letters."The Washington Post

-

"Like Edgar Allen Poe, Palahniuk is a bracingly toxic purveyor of dread and mounting horror. He makes nihilism fun."Vanity Fair

-

"Dark riffing on modernity is the reason people read Palahniuk. His books are not so much novels as jagged fables, cautionary tales about the creeping peril represented by almost everything."Time

- On Sale

- Jan 7, 2020

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538717950

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use